ADHD vs. PTSD

ADHD vs. PTSD (or ADHD and PTSD)

Buckle up; this is a complex one. There are different perspectives when it comes to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). While some clinicians argue that we are overdiagnosing trauma as ADHD, others argue we are over-diagnosing PTSD and missing the ADHD.

Complicating matters, PTSD and ADHD commonly occur together. ADHD makes a person more vulnerable to developing PTSD after a traumatic event and can intensify PTSD symptoms. And trauma may activate ADHD in those genetically predisposed to it. As I said, it’s complex, so let’s dive in!

ADHD Overview

ADHD is classified as a neurodevelopment condition. Meaning the onset occurs during the developmental period (typically early childhood) and has a strong genetic component. As a neurodevelopmental condition, ADHD is considered an innate neurodivergence (meaning a person is born with it).

The parts of the brain that regulate emotions, attention, and focus are impacted by ADHD. ADHD has the following characteristics:

Difficulty regulating attention

Hyperactivity and impulsivity

When it comes to ADHD diagnosis, there are three potential classifications :

ADHD-I is characterized by difficulties regulating attention

ADHD-H is characterized by impulsive and hyperactive behavior

ADHD-C is characterized by both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity

While present from birth, ADHD may not be noticeable until demands exceed capacity (for example, when a person starts college and their workload becomes more intense or after the birth of a second child). Many children develop sophisticated compensatory strategies to offset areas of struggle. In these cases, it may be even later in life that the person's ADHD is recognized.

ADHD Prevalence Rates

ADHD is the most commonly diagnosed developmental condition in the U.S. It has an estimated prevalence rate of 5-11% (Allely, 2014; Visser et al., 2014). According to the CDC, current estimates suggest that approximately 11% of children in the U.S. are ADHDers.

The prevalence rate of ADHD among adults is lower (4.4%) (CDC). This could mean: 1) there is an increase in ADHD, or 2) we have gotten better at detecting ADHD, and there is a higher rate of undiagnosed ADHD adults.

The criteria for diagnosing ADHD include:

The presence of inattention

Impulsivity and hyperactivity (or just inattention for ADHD-inattentive type)

The traits must interfere with daily functioning in at least two contexts (for example: home and school or work and home). Some common ADHD experiences include:

Difficulty focusing or staying on task

Problems keeping track of materials

Trouble following through on complex projects

Distractibility and forgetfulness

Appearing not to listen when spoken to

Increased need to be up and moving

Fidgetiness

Impulsivity

Tendency to interrupt others

Excessive talking

PTSD Overview

Now that we've overviewed ADHD, let's do a refresher on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD results in the aftermath of a traumatic event—impacting brain chemistry and brain wiring. However, the majority of people who experience a traumatic event do not go on to develop PTSD.

PTSD is also considered a form of neurodivergence. However, this is an acquired neurodivergence (meaning it is situational and can be resolved through treatment). At this point, the person may return to their neurotypical baseline. Note: ADHD, on the other hand, is considered an innate neurodivergence (meaning it is present from birth and a core part of a person's identity).

Prevalence Rates of PTSD

A common misconception is that people always develop PTSD following significant trauma. However, while an estimated 50-60% of people experience a significant trauma in their lifetime, only 5-10% of people go on to develop PTSD (Aupperle et al., 2011).

ADHDers experience elevated rates of PTSD. There are various theories about how our neurobiology may make us more vulnerable—from having less flexible nervous systems to difficulty regulating attention to more intense sensory experiences and sensory encoding of the trauma.

Overview of PTSD

PTSD occurs when a traumatic event impacts a person's brain to such a degree that it results in changes to brain wiring and brain chemistry. In the aftermath of trauma, a person may feel chronically unsafe. The brain rewires in such a way as to try and keep the person safe.

For example, when the amygdala—the "safety alarm" of the brain—becomes hyperalert, this results in hypervigilance. The brain is constantly scanning its environment for threats. This hypervigilance impacts things like attention, focus, and the ability to regulate difficult emotions.

The stress response (nervous system) also becomes overactive (i.e., fight-or-flight response). This creates abnormal amounts of adrenaline and cortisol, which causes hyperarousal of the nervous system. Like the amygdala, the fight-or-flight system is working in overdrive in an attempt to protect the body from future danger.

PTSD Intrusion Symptoms

Intrusive symptoms are a core feature of PTSD. Intrusive symptoms may show up as intrusive memories, flashbacks, or nightmares. When an intrusive memory or flashback occurs, the person may become distracted, impacting things like attention and focus (Crenshaw and Mayfield, 2021).

PTSD Avoidance Symptoms

One way of attempting to deal with the chaos that all of this creates is to engage in avoidance strategies. Avoidance strategies are activities the person does to avoid difficult emotions, thoughts, and places.

The problem with avoidance strategies is they tend to cause our anxiety to worsen and deepen (vs. heal and improve). The more the person avoids memories, thoughts, associations, or emotions related to the trauma, the more intense the symptoms of PTSD become.

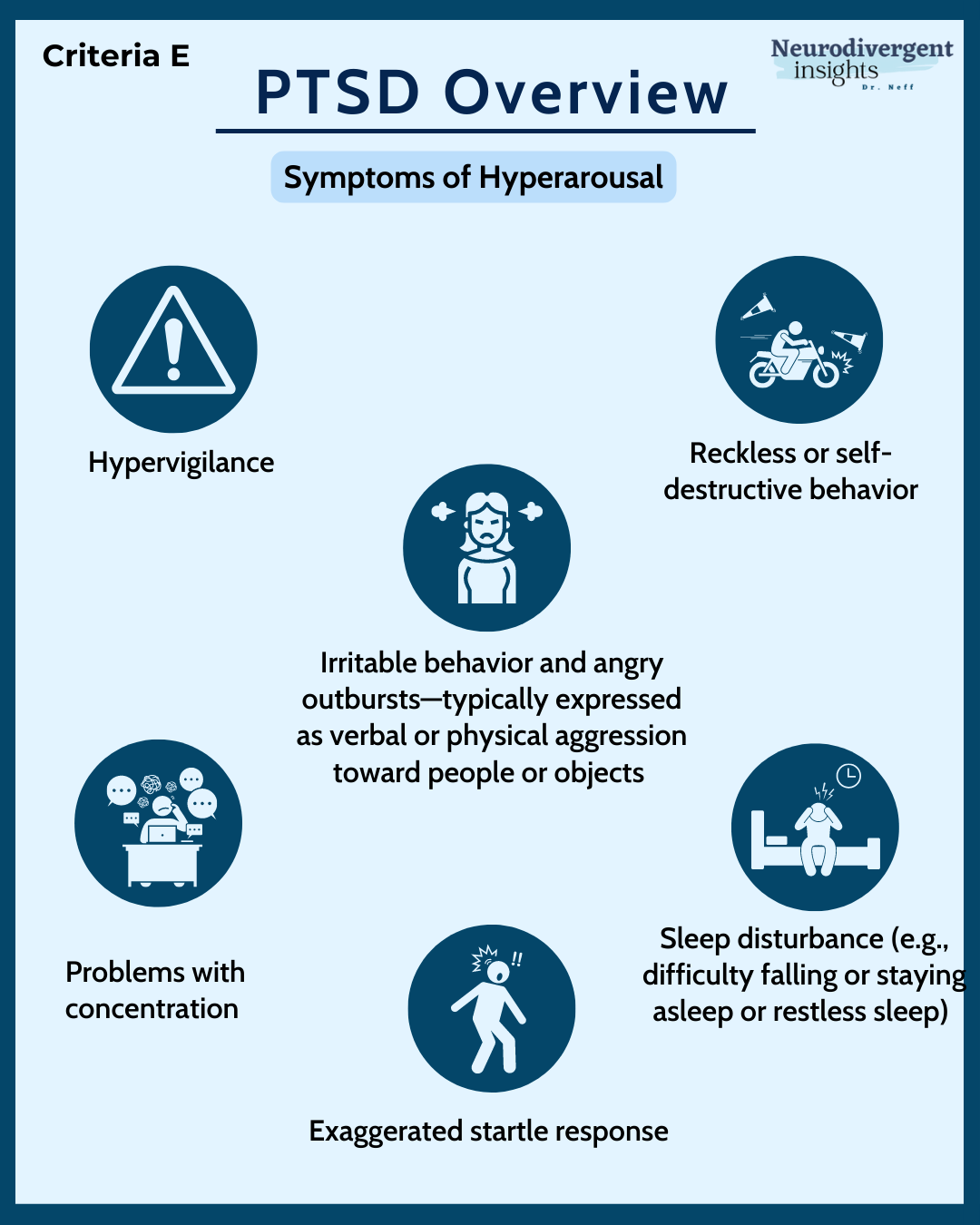

PTSD Hypervigilance Symptoms

The body is on hyper-alert following a traumatic event. The person often experiences exaggerated startle responses, physical agitation, irritability, and sleep disturbances. This negatively impacts executive functioning and makes things like focus, concentration, and attention more difficult.

Complex Trauma

Before leaving the conversation of PTSD, a brief word on complex and developmental trauma—despite countless experts advocating for complex and developmental trauma to be included in the DSM, it has yet to be adopted and is not a formal diagnosis.

The main difference is that PTSD is generally related to a single event or series of events, while complex trauma is related to events that repeatedly occur over an extended period, typically in childhood.

Complex trauma will share many qualities with PTSD while having distinct features.

What is Complex Trauma?

Persistent exposure to traumatic experiences in childhood influences a child's brain when the brain is most vulnerable. A child's brain is particularly neuroplastic, meaning it more easily adapts and shifts to its environment. When the environment is traumatic, the child's brain is heavily shaped by this.

Therefore, children with complex trauma will often continue to experience symptoms even as they move into adulthood, and the symptoms are unlikely to fade entirely (although will improve with treatment). The symptoms are vulnerable to re-emerging, particularly during stress.

Many survivors of complex childhood trauma continue to struggle with symptoms into adulthood. These symptoms may look like ADHD (Crenshaw and Mayfield, 2021). Alternatively, if a person has both, their ADHD may be dismissed due to the presence of complex trauma.

Co-Occurrence of ADHD and PTSD

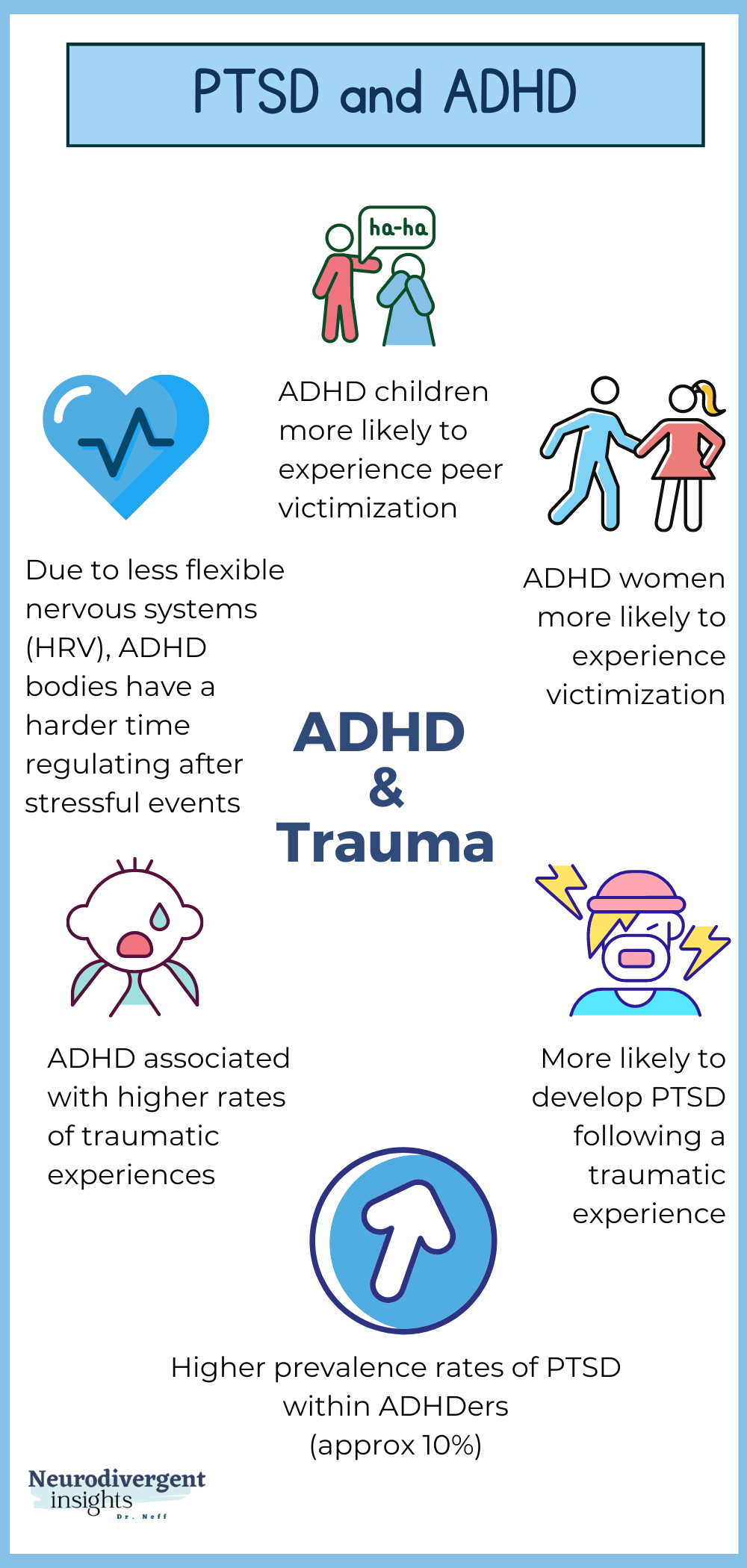

There are many reasons it is difficult to distinguish between ADHD and PTSD, perhaps the most notable reason being—they commonly occur together! The fact PTSD and ADHD so commonly co-occur is one of the reasons they are so difficult to distinguish (Biederman et al., 2012).

PTSD and ADHD appear to have a bi-directional relationship (bi-directional means it goes both ways, and they impact one another). For example, ADHD is a risk factor for developing PTSD (Gurvits et al., 2000), and exposure to complex trauma in childhood may activate ADHD in those genetically predisposed to it (Crenshaw and Mayfield, 2021).

Understanding the Link Between ADHD and PTSD

There are several reasons that ADHD and PTSD co-occur. ADHD is thought to be a risk factor for developing PTSD (Adler et al., 2004; Kessler et al. 2006). The following are a few other factors that contribute to their co-occurrence:

1. ADHDers are at an elevated risk for exposure to traumatic experiences (Ford et al., 2009).

2. ADHDers have more sensitive nervous systems, which means traumatic events negatively impact them, making them more likely to develop PTSD following a traumatic event.

3. Early life trauma may function as a trigger for those genetically predisposed to ADHD (Crenshaw and Mayfield, 2021).

Prevalence Rate of Co-Occurring PTSD and ADHD

While it is difficult to discern the true prevalence rate of how often PTSD and ADHD co-occur, the following is a summary of several research studies:

Adler et al. (2004) found that 36% of the veterans who met the criteria for PTSD had co-occurring ADHD.

Gurvits et al. (2000) found that 30% of people with PTSD had ADHD symptoms in childhood (compared to 11% of adults without PTSD).

Biederman et al. (2012) found significantly higher rates of PTSD among adolescents with ADHD.

El Ayoubi et al. (2020) found that the prevalence of PTSD was higher in ADHD patients seeking substance abuse treatment (84% vs. 40% of non-ADHDers seeking substance abuse disorder treatment).

Treatment Implications

When they co-occur, the symptoms tend to exacerbate one another, and the person tends to experience more daily struggles and suffering.

ADHD is associated with having experienced more traumatic events. And, on the flip side, the co-occurrence of ADHD is correlated with more severe PTSD symptoms (compared to people with PTSD who did not have ADHD) (Crenshaw and Mayfield, 2021).

It is critical that treatment consider both PTSD and ADHD and the compounding stressors of living with both. Given the additional layers of complexity, it is critical to diagnose and treat both.

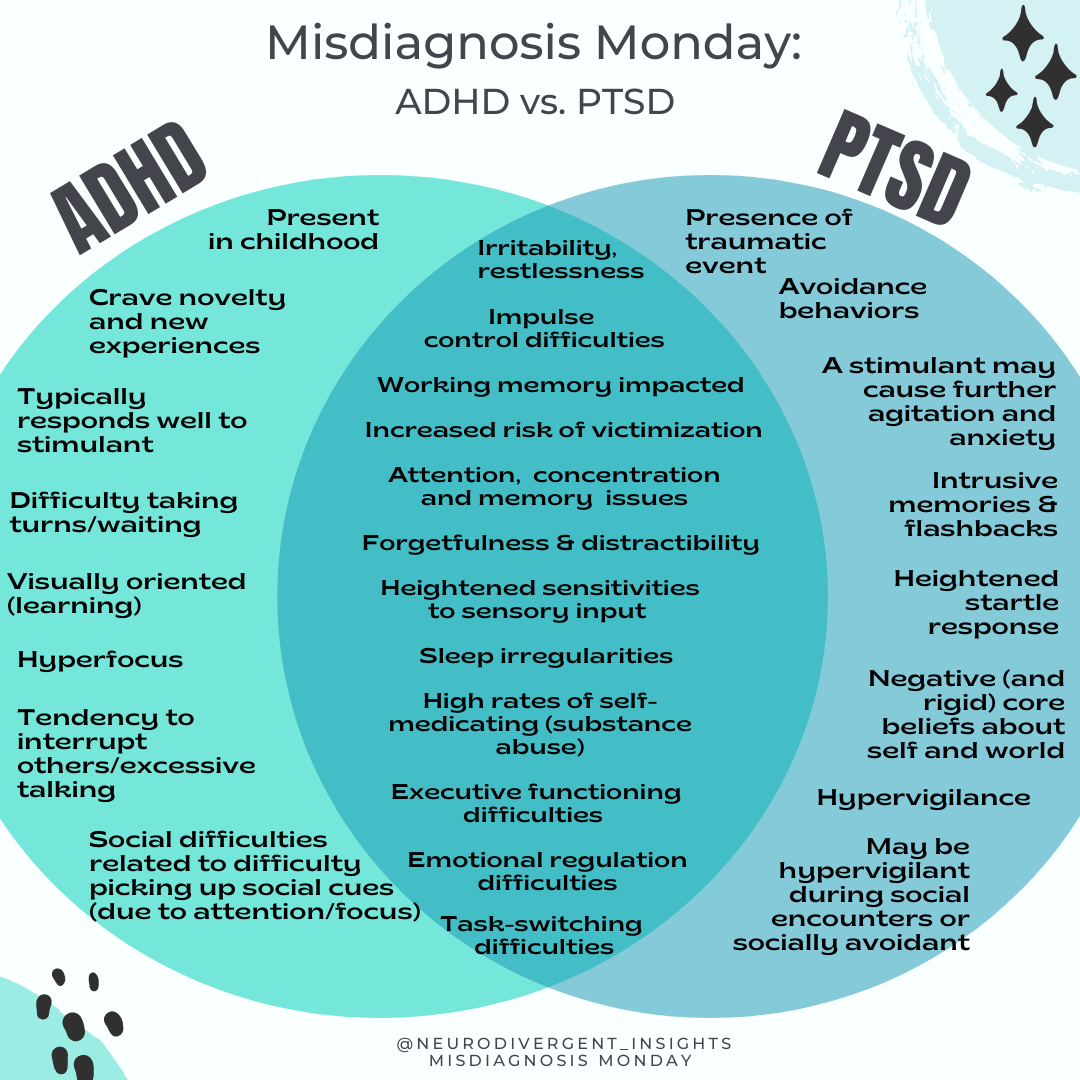

Overlapping Traits Between PTSD and ADHD

One factor that makes it difficult to distinguish ADHD from PTSD is the high level of co-occurrence. The second factor that makes it difficult to distinguish these conditions is the level of overlapping traits.

They have many overlapping traits. In some cases, the level of symptom overlap can lead to a wrong diagnosis (Szymanski, 2011).

These two conditions share more similarities than differences. In other words, their similarities are greater than their differences, thus making the risk of misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis quite high (Szymanski, 2011).

Similarities between the two include difficulty with focus and concentration, hyperarousal, difficulty regulating emotions, and more. Both conditions impact executive functioning, attention and focus, and sensory processing.

While they have different origins, they are hard to distinguish and are often easily mistaken for the other because they present so similarly. Both experience:

Inattention

Difficulty with impulse control

Deficits in working memory

Difficulty with focus and attention

Sleeplessness and sleep disruptions

Distractibility

Impulsivity

Irritability

Poor memory and concentration

Anxiety

Heightened sensory sensitivities

Mood disorder

Low self-esteem

Increased risk of substance abuse

Executive Functioning Difficulties

Executive functioning is impacted both in the context of ADHD and PTSD. While the cause of executive functioning differs, on the outside it can look similar, making it difficult to distinguish the two.

Executive functioning challenges are a core feature of ADHD and have to do with neurodevelopmental differences. Areas of the brain often impacted by ADHD include: working memory, ability to regulate attention and focus, emotional regulation, inhibition, and the ability to break down large tasks into smaller tasks.

With PTSD, distractibility from intrusions and hypervigilance overloads the brain. The cognitive overload impacts executive functioning in ways that look similar to ADHD. This is complicated further if the trauma happened in early childhood. This is because PTSD rewires the brain, stunting the growth of areas that deal with emotional regulation and impulse control (Crenshaw and Mayfield, 2021).

Working Memory

Working memory is the ability to hold and manipulate information in mind (for example, when doing complex math in your mind or when trying to remember the 7 things you need to buy from the grocery store).

It is widely known that working memory tends to be impacted in the context of ADHD; however, it is less known that it also is often impacted in the context of PTSD (Swick et al. 2017).

Hyperarousal and intrusive symptoms impact working memory by overloading the brain. When the brain is overloaded it becomes more difficult to hold information in mind. This means people are less able to hold and manipulate information and may struggle with tasks requiring short-term memory.

Difficulty Regulating Attention

It is widely known that working memory tends to be impacted in the context of ADHD; however, it is less known that it also is often impacted in the context of PTSD (Swick et al. 2017).

Task Switching

Set-shifting and task-switching can be difficult for the ADHD brain. This involves shifting attention quickly from one area of focus to another.

The Stroop-Task and Trail-Maker test are two neuropsychological assessments commonly used when diagnosing ADHD. It assesses the person's ability to quickly and accurately shift attention from one task to another.

Swick et al. (2017) found that people with PTSD also struggled with these assessments. People with PTSD also had difficulty task switching on the Stroop-task and trail-maker test. Both of these tests are timed and involve rapidly shifting attention from one task to another. (Swick et al. 2017).

Hyperarousal vs. Hyperactivity

Hyperarousal can look like hyperactivity and vice versa. Hyperarousal (which is a natural response to the body’s overactive fight or flight response) is characterized by increased arousal, agitation, anxiety, hyper-vigilance, irritability, and an exaggerated startle response.

Hyperarousal symptoms will look a lot like hyperactivity (i.e., fidgeting, excessive moving, stimming, and restlessness) (Szymanski, 2011).

Disorganization

A key feature of ADHD is difficulty organizing thoughts and tasks. Intrusive memory can also cause disorganized thought patterns. Intrusive thoughts and re-experiencing of traumatic memories can look like ADHD difficulty with organization and listening (Szymanski, 2011).

Flashbacks/Impulsivity

Flashbacks create intense emotions. The anxiety and emotional flooding of flashbacks can lead to impulsive behavior. This makes it difficult to tease out emotional flooding/flashbacks from trait impulsivity. This is particularly true for children. When children re-experience the trauma, this can overwhelm their systems and lead to chaotic, impulsive, and agitated behaviors that look like ADHD impulsivity (Szymanski, 2011).

Avoidance vs. Inattention

Avoidance is a key component of PTSD and is one of the behaviors that perpetuate PTSD. Avoidance can involve cognitive, behavioral, relational, and emotional avoidance.

Avoidance can include intentional efforts to not think about things that remind the person of their trauma or to avoid specific stimuli that remind them of the trauma.

Particularly when the avoidance is cognitive (internal), this takes a great deal of focus. This can result in a high level of distractibility and forgetfulness which looks like the inattention cluster of ADHD (ADHD cluster A) (Szymanski, 2011). As such, avoidance can look like inattention.

On the flip side, inattentive daydreaminess may look like PTSD dissociation and avoidance and be misattributed to trauma.

Sensory Sensitivities

Sensory differences are not included in the DSM-5 criteria for ADHD or PTSD. However, it is common to see sensory processing differences among ADHDers. Both hyper-responding and hypo-responding to sensory input have been observed in children with ADHD.

Similarly, people often develop hypersensitivity to sensory input because of the hyper-activation of the nervous system during PTSD. The brain is working in overdrive to detect signs of threat; as such, it tends to take in sensory information with more intensity. When PTSD is treated, the person's sensory profile will become less hypervigilant and return to a more normative way of processing sensory information.

Emotional Regulation

ADHDers and people with PTSD often experience difficulty managing difficult emotions. In both conditions, it is common to be overwhelmed by the intensity of emotions.

Emotion dysregulation is a broad term that captures multiple dimensions of how a person experiences and interacts with their emotions. Emotional dysregulation includes:

A lack of awareness, clarity, or acceptance of emotions

Difficulties controlling behaviors when distressed

Limited access to strategies that help to self-soothe and regulate emotions

Active avoidance of distressing emotions

(Gratz and Roemer, 2004; Gratz and Tull 2010b)

ADHDers and people with PTSD struggle with emotional dysregulation for several factors, some of which include:

Neurological vulnerabilities (more sensitive amygdalas)

More rigid nervous systems (reduced heart rate variability)

Alexithymia (difficulty identifying and describing feelings)

Hyperarousal/hyperactivation of the nervous system

Executive functioning difficulties

Difficulty with regulating emotions can lead to co-occurring depression and anxiety and result in relationship difficulties.

Implications

It is recommended that a person be screened for a history of PTSD when assessed for ADHD. Assessment of ADHD should include screening for psychological trauma history and PTSD. When they co-occur, treatment of ADHD may also help to ameliorate PTSD. In addition, PTSD treatment may support ADHD treatment by reducing anxiety and stress-reactivity (which can exacerbate ADHD) by contributing indirectly to inattention or impulsivity.

Clinician’s Corner: How to Spot the Difference Between PTSD and ADHD

While not an exhaustive list nor a replacement for clinical training in these areas, here are some data points to consider when trying to tease out whether it is PTSD vs. ADHD or PTSD and ADHD:

Consider the timeline

Routinely screen for both (with caution)

Identify causes of inattention

Focus on the distinguishing features

Focus on ADHD-Inattentive traits

Consider the Timeline

This will be easier when working with adults and in the context where there is one specific trauma (vs. diffuse developmental trauma or complex trauma).

For a diagnosis of ADHD, traits must present before the age of 12. However, you will also want to remember that ADHD is a risk factor for experiencing victimization and trauma. With this in mind, the person may have had compensatory strategies, making it challenging to detect ADHD. The trauma may have been the critical factor that caused the supports to fall away and act as the stressor that caused the ADHD traits to become more noticeable. Particularly in the case of twice-exceptional or high-achieving ADHDers, it is common for ADHD not to become noticeable until life stress exceeds the person's ability to cope.

Outside of the age of onset, it is essential to consider the person's baseline experience vs. post-traumatic experience. For example, if the client has no history of inattention, hyper-activation, or difficulty with focus, this is not considered part of their baseline.

However, if the person reports a historical difficulty with these areas that PTSD exacerbates, you should consider the possibility of ADHD and PTSD. The goal is to get a sense of the person's baseline experience vs. their post-trauma experience.

The goal is to get a sense of the person's baseline experience vs. their post-trauma experience.

Screen for Both PTSD and ADHD

Given the high rate of co-occurrence, screening for ADHD when diagnosing PTSD and vice versa should be routine. From my observation, PTSD screeners are frequently included in ADHD assessments, while ADHD screeners are rarely included in PTSD assessments.

What follows are some screeners that can easily be incorporated into a psychological assessment (all available for free and online):

ADHD Screeners

For Children:

*The ASRS is likely to have false positives when used in a PTSD population. Using this in conjunction with the Wender Utah ADHD rating scale will increase specificity. However, it is still essential to be aware that PTSD symptoms will cause there to be false positives when relying on ADHD screeners alone. Therefore, it should always be followed up with a clinical interview, such as the DIVA-5.

PTSD Screeners

When assessing for ADHD, it is important to consider whether the experiences are attributed to ADHD or undiagnosed PTSD. Therefore, it is recommended to include PTSD screeners in your ADHD assessments. The following are screeners that can easily be incorporated into a psychological assessment for ADHD:

Identify Causes of Inattention

Inattention, difficulty with focus, and distractibility are core features of PTSD and ADHD. It is essential to get beneath the behavior and understand the trigger, cause, and experience of the person to distinguish between ADHD and PTSD.

PTSD Distractibility

PTSD distractibility can look like ADHD distractibility but is different in nature. With PTSD, inattention is due to hypervigilance (for example, constantly scanning the environment for signs of threat). A person may also be distractable because of intrusive memories, traumatic memories, and internal reactions to trauma flashbacks/triggers.

Strong avoidance tendencies also characterize PTSD. The person is working very hard to avoid both external situations and internal experiences (memories, sensations, emotions, and thoughts) that remind them of the trauma. The act of avoiding these stimuli requires a significant amount of executive functioning!

ADHD Distractibility

In the case of ADHD, inattention is related to attention regulation difficulties, particularly when fatigued or when the topic has little inherent interest for them. A person with ADHD often becomes distracted by new thoughts, sounds, or external stimuli. Their ability to regulate their focus and attention will increase when they are engaged in the area of interest or have a sense of urgency.

ADHD conversations often have a distinct feel to them. Neurodivergent conversations are interconnected. We often connect ideas. At times our listener may be confused about how we jumped from talking about topic A to topic B; however, the ADHDer will likely be able to articulate how and why these concepts relate in their mind.

*It is important to get a sense of inattention and distractibility in childhood. Did they make mistakes on exams, forget to turn in assignments, etc.

Focus on the Distinguishing Features

Consider Intrusive and Avoidance Symptoms

The intrusive and avoidant symptoms distinguish PTSD from other conditions (see pages 16-17 and 19-20 from section one).

Consider Hyper-Focus

ADHDers tend to become powerfully focused on areas of high interest. They may describe feeling as if they lose track of time or "go into a vortex." In the context of ADHD, the person has less difficulty regulating attention when it is an area of particular interest. They may have prolonged periods of hyperfocus on a subject of interest. Such periods of prolonged hyperfocus would not indicate PTSD alone and would be a distinguishing factor.

Social Differences

You may also observe subtle social differences. In the context of ADHD-combined or hyperactive type, the person may talk excessively, interrupt others or have difficulty picking up on social cues due to attention and focus difficulties.

Those with ADHD-inattentive type may be prone to withdraw internally, describing themselves as "shy" and "timid" and becoming distracted during conversation as they engage in their intricate fantasy and daydream life.

The person with PTSD may respond in a variety of ways; however, they are likely to be more hypervigilant in social interactions (vs. inattentive). Alternatively, they may experience dissociation and appear socially withdrawn.

Further Resources

Trauma Resources for Clinicians

CE Webinars and Certificate Courses

(Trauma focused)

Featuring Stephen Porges, Peter Levine, Linda Curran, Richard Schwartz, Janina Fisher, and more!

Certificate: Certified Clinical Trauma Professional Level 1

Good for clinicians wanting comprehensive training in trauma

Great for clinicians working with teenagers or others wanting to integrate special interests, passions, superheros or pop culture into their work with teens and young adults.

Trauma Resources for Individuals

Self-Care Tips and Trauma: This website provides several helpful strategies for coping with PTSD.

Psychological First Aid: The VA provides several manuals and handouts with lots of great resources and interventions for treating people in the aftermath of trauma.

Grounding: Utilizing grounding techniques is foundational in trauma work. Check out my free PDF with grounding exercises and info.

Sensory Soothers: Consider having extra sensory soothers and fidgets around the house to access energy. Fidgets can also function to help with tactile grounding.

ADHD workbooks or check out my collection of ADHD favorite books

Or check out some of my favorite executive function helpers or sleep supports

References

Adler, L. A., Kunz, M., Chua, H. C., Rotrosen, J., & Resnick, S. G. (2004). Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in adult patients with Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Is ADHD a vulnerability factor? Journal of Attention Disorders, 8(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705470400800102

Biederman, J., Petty, C. R., Spencer, T. J., Woodworth, K. Y., Bhide, P., Zhu, J., & Faraone, S. V. (2013). Examining the nature of the comorbidity between pediatric attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 128(1), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12011

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R et al.The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry2006; 163: 716– 723. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16585449/

Ford, J. D., Racusin, R., Ellis, C. G., Daviss, W. B., Reiser, J., Fleischer, A., & Thomas, J. (2000). Child maltreatment, other trauma exposure, and posttraumatic symptomatology among children with oppositional defiant and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders. Child maltreatment, 5(3), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559500005003001

Ford, J.D., Connor, D.F. (2009). ADHD and posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr Atten Disord Rep 1, 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12618-009-0009-0

El Ayoubi, H., Brunault, P., Barrault, S., Maugé, D., Baudin, G., Ballon, N., & El-Hage, W. (2020). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Is Highly Comorbid With Adult ADHD in Alcohol Use Disorder Inpatients. Journal of attention disorders, 1087054720903363.

Gurvits, T. V., Gilbertson, M. W., Lasko, N. B., Tarhan, A. S., Simeon, D., Macklin, M. L., Orr, S. P., & Pitman, R. K. (2000). Neurologic soft signs in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 57(2), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.2.181

Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Barkley, R., Biederman, J., Conners, C. K., Demler, O., Faraone, S. V., Greenhill, L. L., Howes, M. J., Secnik, K., Spencer, T., Ustun, T. B., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2006). The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The American journal of psychiatry, 163(4), 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.716

Swick, D., Cayton, J., Ashley, V., & Turken, A. U. (2017). Dissociation between working memory performance and proactive interference control in post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychologia, 96, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.01.005

Szymanski, K.; Sapanski, L. & Conway, F. (2011) Trauma and ADHD – Association or Diagnostic Confusion? A Clinical Perspective, Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 10:1, 51-59, DOI: 10.1080/15289168.2011.575704