Schizoid PD vs. Autism

Schizoid Personality Disorder vs. Autism

Before discovering my autism, I would frequently reference my “schizoidness”. At the time, this was the only language I had to describe my relational peculiarities. I was often perplexed by the paradox I seemed to occupy—being a deeply relational, empathetic soul who cares about humanity while also struggling with the realities of being with fellow humans in physical space.

I have very low social energy and can be quite self-preserving. It takes a lot for me to subject my body to socializing. And while I crave deep connection, I don’t need many social interactions to sustain me. I crave solitude and alone time and would nearly always prefer to be alone when given the option. Positive emotions overwhelm me, and I can have a flat affect when I’m not in a performative mode. When I discovered my autism, it helped me understand these parts of me--it turns out that what I was calling my “schizoidness” for years was actually just my autism.

And while aspects of the schizoid personality structure resonate, other pieces certainly do not (I am not indifferent to relationships, and I value other people’s opinions and seek external validation more than I care to admit). Given the years I spent identified as being on the schizoid spectrum, it is no surprise to me that Schizoid Personality Disorder and Autism have a high level of overlap. They can be difficult to distinguish from one another.

Overview of Schizoid Personality Disorder

Schizoid PD is characterized by detachment and indifference to social relationships, interactions, and engagement. Such folks have limited social interest and may have little interest in sexual activities with others. Others may describe them as a “loner” or “isolated.” However, this doesn’t cause the person distress or pain.

People with Schizoid PD go to great lengths to avoid social interactions—arranging their whole lives in such a way as to reduce contact. They actively seek occupations with limited social interaction, may avoid romantic relationships, and generally organize their lives to avoid people. They often consider themselves to be “observers” or “bystanders” rather than participants in society (Esterberg et al., 2010).

Such folx tend to have a high value of self-sufficiency and independence and actively avoid activities that diminish their sense of autonomy (such as intimate relationships). They often have concrete thought processes, and speech, mental rigidity, impaired empathy, limited eye contact, and flat affect in tone and expression (Esterberg et al., 2010; Martens, 2010). It is more common among men and is estimated to affect approximately 3.1-4.9% of the population nationally (Zimmerman, 2021). It is more common among those who have a relative with autism or schizophrenia.

Previously I talked about the genetic and phenotypic link between schizophrenia and autism. Schizoid PD could be said to sit in the middle of these two conditions. Schizoid PD shares many overlapping traits with schizophrenia. The negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia are present in Schizoid PD, while the positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions, etc.) are absent (Nirestean et al., 2012)

DSM-5 Criteria for Schizoid Personality Disorder

For a person to meet the criteria for Schizoid PD, there must be: A pervasive pattern of detachment from social relationships and a restricted range of expression of emotions in interpersonal settings, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by four (or more) of the following:

Neither desires nor enjoys close relationships, including being part of a family.

Almost always chooses solitary activities.

Has little, if any, interest in having sexual experiences with another person.

Takes pleasure in a few, if any, activities.

Lacks close friends or confidants other than first-degree relatives.

Appears indifferent to the praise or criticism of others.

Shows emotional coldness, detachment, or flattened affectivity.

These things must not occur exclusively during the course of schizophrenia, a bipolar disorder or depressive disorder with psychotic features, another psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder and is not attributable to the physiological effects of another medical condition.

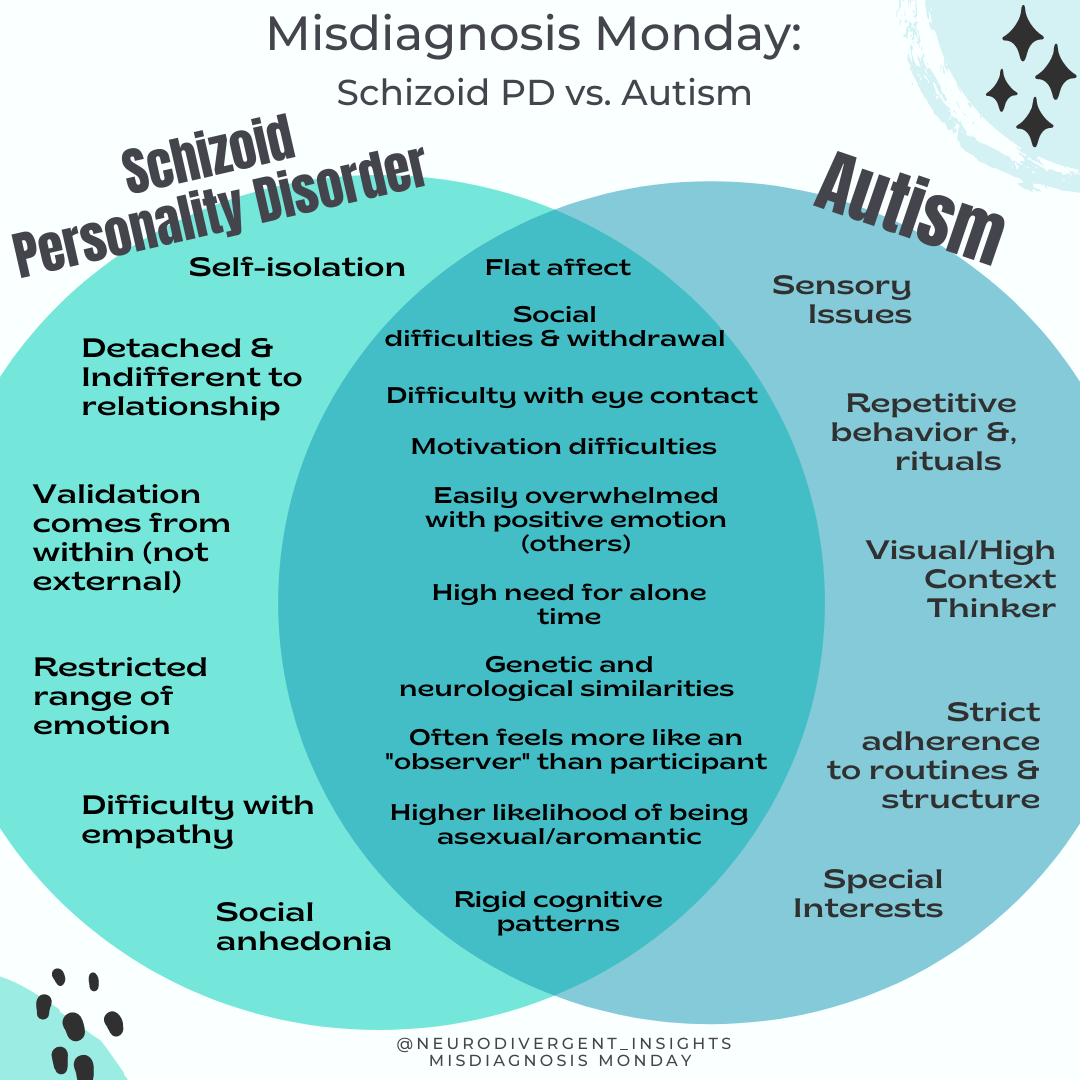

Overlap of Schizoid PD and Autism

It can be challenging to discern accurate numbers of co-occurrence between Autism and Schizoid personality disorder. And while an Autistic person may meet the criteria for Schizoid PD, if their symptoms are explained by their ASD, they should not be doubly diagnosed per DSM-5 criteria.

The DSM emphasizes the difficulty in distinguishing between these two disorders and, in fact, notes that before a diagnosis of Schizoid PD is given, pervasive developmental disorder (such as Autism) must be ruled out. (Lugnegard et al., 2012).

Several studies have found that a high percentage of Autistic people also meet the criteria for schizoid personality disorder. Lugnegard et al. 2012, found that 14 out of the 54 individuals with Autism also met the criteria for Schizoid PD. After studying the shared phenological overlap, Lugnegard et al. 2012, went so far as to question the concept of “pure” schizoid personality disorder in the absence of a pervasive developmental disorder (i.e., Autism).

Historically schizoid PD has been more prevalent than ASD; however, with the number of Autism diagnoses rising, it is speculated there may be a lost generation of adults who escaped diagnosis in childhood. One speculation is that perhaps one of the reasons for the discrepancy between the rate of schizoid PD and Autism is that Autistic people who were not diagnosed in childhood were later diagnosed with schizoid PD in adulthood. Cook et al., 2020 considers whether or not we will see the prevalence of these conditions equalize now that more children are being diagnosed with Autism:

The exponential rise in the prevalence of Autism has been accompanied by data that confirms the enduring nature of the condition throughout life (Fountain et al., 2012; Wagner et al., 2019). Historically, the prevalence of ASD has been deemed much lower than that for schizoid PD, but the cohort of children who have been diagnosed over the past twenty years—and who might not have been historically diagnosed in childhood—are now aging into adulthood. Many such individuals exhibit schizoid PD symptomatology and may account for cases of schizoid PD that historically would have been assumed to have had onset in adulthood. These data support overlap and possible developmental continuity between the two conditions and may help reconcile historic contrasts in their respective prevalence over the life course (Cook et al., 2020).

Supporting Cook’s speculation, it seems probable that Schizoid PD may become a diagnosis that catches Autistics later in life. While Autism is commonly diagnosed in childhood and rarely diagnosed in adulthood, Schizoid PD is the opposite-rarely diagnosed in childhood and commonly diagnosed in adulthood. Thus, it seems probable those who would have been diagnosed with Autism in childhood may be diagnosed with Schizoid PD in adulthood if they have escaped childhood without an autism diagnosis.

Genetic and Phenotypic Overlap

Genetic and neuroimaging studies further reinforce the argument for a shared phenotype between Schizoid PD and Autism. A link between these disorders has been observed in genetic and neuroimaging studies (Ford and Crewther, 2014). Some have speculated that schizoid personality disorder and autism are likely on a similar spectrum as they share many genetic links, and many people with Schizoid PD may be on the broader autism phenotype. Schizoid traits have been found to be more common in parents of children with autism (Wolffe and Moyes, 1988).

Ford & Crewther, 2014 did a cluster analysis to evaluate whether or not Schizoid PD and autism shared a similar phenotype or were distinct. They found a shared phenotype, particularly regarding social and communication patterns present in both disorders. From social avoidance and discomfort to restricted emotional range and discomfort with eye contact, there are many shared features between Schizoid PD and Autism.

I want to nuance this by saying I suspect the shared phenotype is most robust among autistics who have little or limited social motivation. Tony Attwood describes three distinct social profiles among autistics that I find to be a helpful conceptualization:

The person with limited social motivation: This is the person who has found objects, ideas, and things to be more interesting than people. The child who gets lost in the world of building Lego or inventions over being with people (These types are often autistic people who do not also have co-occurring ADHD

The socially motivated person who has difficulty reading social cues: They are socially motivated but tend to miss social cues from others. They can be a bit clumsy/unaware when interacting with others. Others often describe these folks as intrusive or overbearing (often, but not always, these are the ADHD/Autism types)

The social chameleon: These people are socially motivated and aware of the fact they’re missing social cues. So, they analyze and adapt themselves to fit those around them. The first and second social profiles are most consistent with the “stereotypical” presentation of autism, while the third often goes undetected due to their ability to mask.

Social profile 1 and schizoid PD have a great deal in common, while social profiles 2 and 3 have less overlap. Thus, the most common misdiagnosis likely happens with the autistic person who has limited social motivation.

Shared Experiences

While this is not an exhaustive list, some common shared experiences between Schizoid PD and the Autistic person are shared.

Reluctant to go to Therapy

People with Schizoid PD typically don’t go to therapy, and if they are there, it’s often because someone in their life is insisting. They may be slow to open up to and trust a therapist. Similarly, Autistic people tend to have a complex relationship to therapy; I’ve talked previously about some of the aspects of therapy that can be hard for many of us. Therapy can feel intrusive and uncomfortable, so many of us may try therapy and drop out after a few visits.

Closeness as Intrusion

Both groups may experience emotional intimacy as intrusive.

Easily Overwhelmed by Others' Emotions

Both may experience other people’s emotions as overwhelming (particularly positive emotions). Many autistic people absorb the negative emotions of those around them. This can contribute to a person’s desire to withdraw and be alone. Folks with Schizoid PD are known to have a flat affect and a restricted range of emotions.

Need for Alone Time

Perhaps due to some of the reasons mentioned above, both groups tend to need and crave a lot of alone time.

Motivation Difficulties

Both may experience difficulties with motivation. For the Autistic, it is often related to having an interest-based nervous system. For the person with schizoid PD, it may be related to anhedonia and a general tendency to receive less pleasure from activities.

Limited Social Pleasure

People who schizoid PD experience limited to no pleasure when socializing. Similarly, Autistic people do not receive dopamine from small talk (as allistics do). However, Autists often experience pleasure when connecting deeply with others or when connecting over a shared interest.

Distinguishing the Difference

Schizoid PD and Autism are notoriously difficult to tease apart. Per the DSM recommendations, Autism should be ruled out when making a diagnosis of schizoid PD. Here are a few things to consider when working to tease out the difference between schizoid PD and Autism.

Consider Social Motivation

In the context of Autism, the person may be socially motivated buts struggle to feel capable of initiating or maintaining friendships. In contrast, the schizoid person does not experience social motivation/desire. As a rule of thumb: People with schizoid PD are more affected by differences in social motivation, whereas those with ASD are more affected by differences in social skills or capacity (Cook et al., 2020).

Rule Out Autism First

The DSM suggests that pervasive developmental disorders be ruled out before diagnosing Schizoid personality disorder. To do this, engage in a thorough developmental history. Consider using routine screeners. The AQ and RAADS are standard routine screeners for Autism. You may also consider including the BAPQ to assess if they are on the broader autism phenotype.

Focus on Criteria B for Autism

Given criteria A symptoms overlap with schizoid Personality symptoms, it is essential to assess for the presence of criteria B symptoms (rigidity and repetitive behaviors, special interests, sensory issues). If a clinician is assessing for schizoid PD but not considering Autism, they won’t assess for these things, and Autism may be missed. The RAADS can be a helpful tool for assessing some of criteria B symptoms.

Repetitive, stereotyped movements, use of objects, and/or speech (i.e., stimming, repeated vocal phrases, lining up or categorizing objects).

The inflexibility of behavior and thought, ritualistic behaviors, concrete thinking (i.e., echolalia, listening to songs on repeat, adherents to routine, tendency to take things literally, and being high context thinkers)

Intense interests and/or attachment to objects (i.e., Special interests)

Sensory processing symptoms (under-reactivity, over-reactivity, or fascination with sensory input.

Citations

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Cook, M. L., Zhang, Y., & Constantino, J. N. (2020). On the Continuity Between Autistic and Schizoid Personality Disorder Trait Burden: A Prospective Study in Adolescence. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 208(2), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001105

Esterberg, M., Goulding, S., & Walker, E. (2010, Dec 1). A Personality Disorders: Schizotypal, Schizoid and Paranoid Personality Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(4), 515-528. Retrieved March 13, 2014, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2992453/

Ford TC & Crewther DP(2014). Factor analysis demonstrates a common schizoidal phenotype within autistic and schizotypal tendency: Implications for neuroscientific studies. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5. [PubMed]

Lugnegard T, Hallberbäck MU, & Gillberg C (2012). Personality disorders and autism spectrum disorders: What are the connections? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(4), 333–340. [PubMed]

Martens, W. (2010). Schizoid personality disorder linked to unbearable and inescapable loneliness. The European Journal of Psychiatry, 24(1). Retrieved March 12, 2014, from http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=S0213-61632010000100005&script=sci_arttext

Nirestean, A., Lukacs, E., Cimpan, D., & Taran, L. (2012, Jan 12). Schizoid personality disorder—the peculiarities of their interpersonal relationships and existential roles. Personality and Mental Health, 6(1), 69-74. Retrieved March 12, 2014, from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2012-03494-007

Wolff S, Narayan S, Moyes B. Personality characteristics of parents of autistic children: a controlled study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry (1988) 29(2):143–53. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00699.x

Zimmerman, Mark. Schizoid Personality Disorder. 2021. Merck Manual Professional Version. Retrieved from: https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/psychiatric-disorders/personality-disorders/schizoid-personality-disorder-scpd