Autism and OCD

As a child, I experienced OCD that often caused overwhelming anxiety. If I didn’t do my OCD goodbye ritual (a compulsion) with my parents, I was terrified they would be dead when I got home from school. If I hadn’t checked for bad guys in just the right way (yes, even checking dresser drawers even though it was illogical), then I was afraid someone would sneak out and grab me. When I touched something with one hand, it would trigger a cascade of touching until I had evened the touch out between both hands, and it felt “just right.”

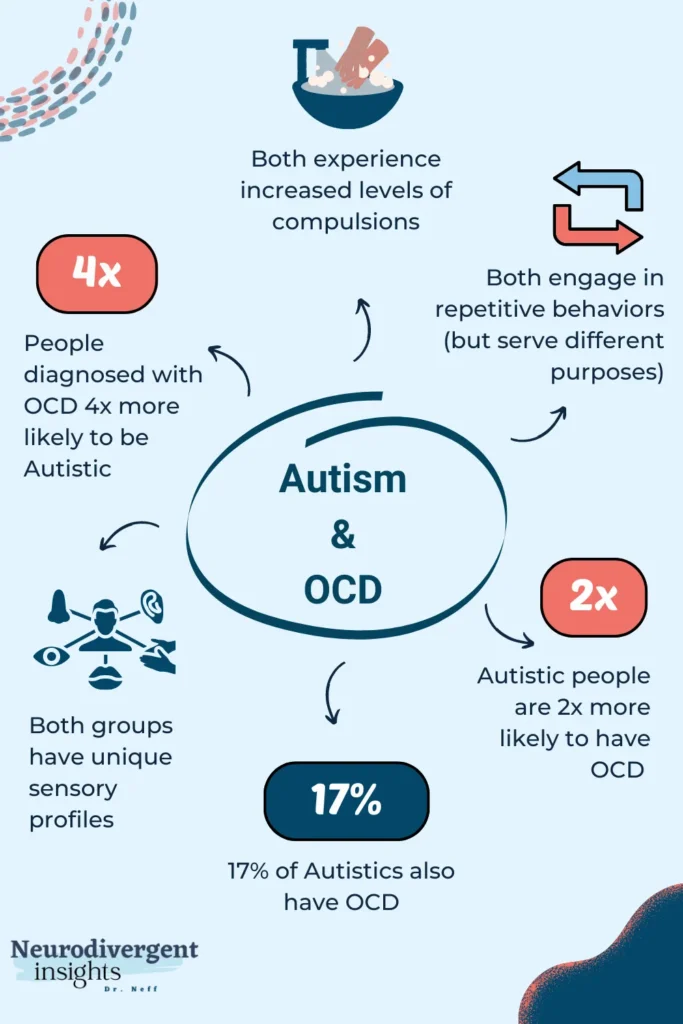

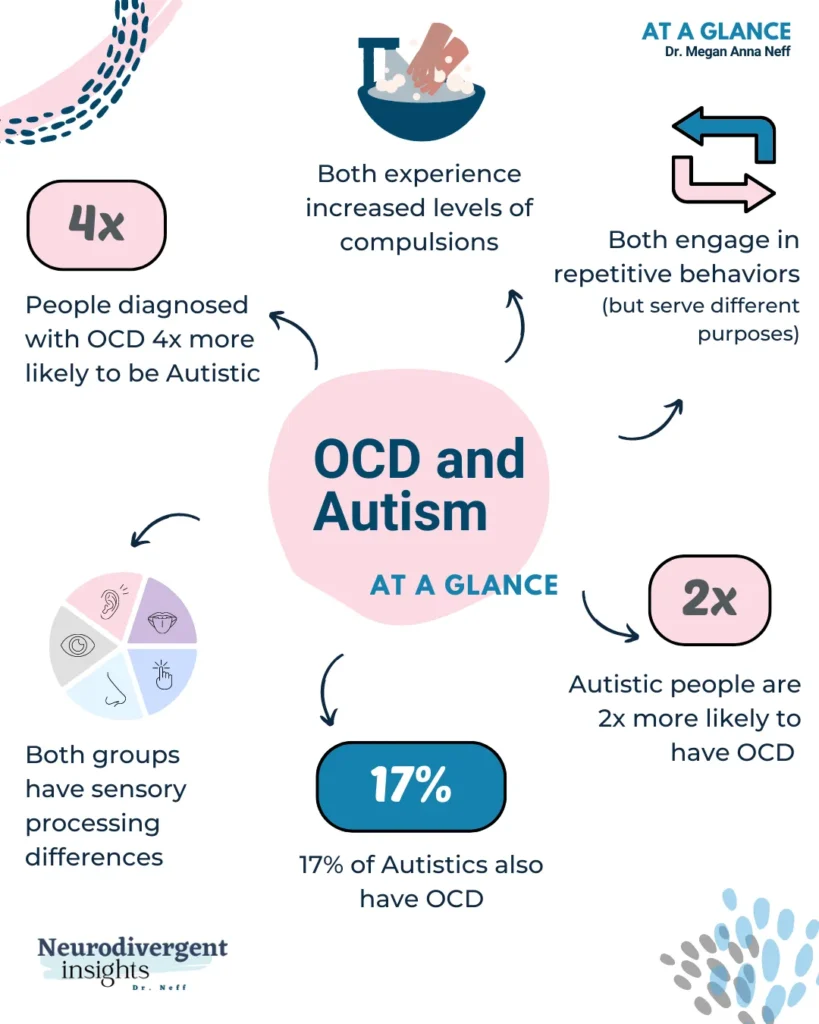

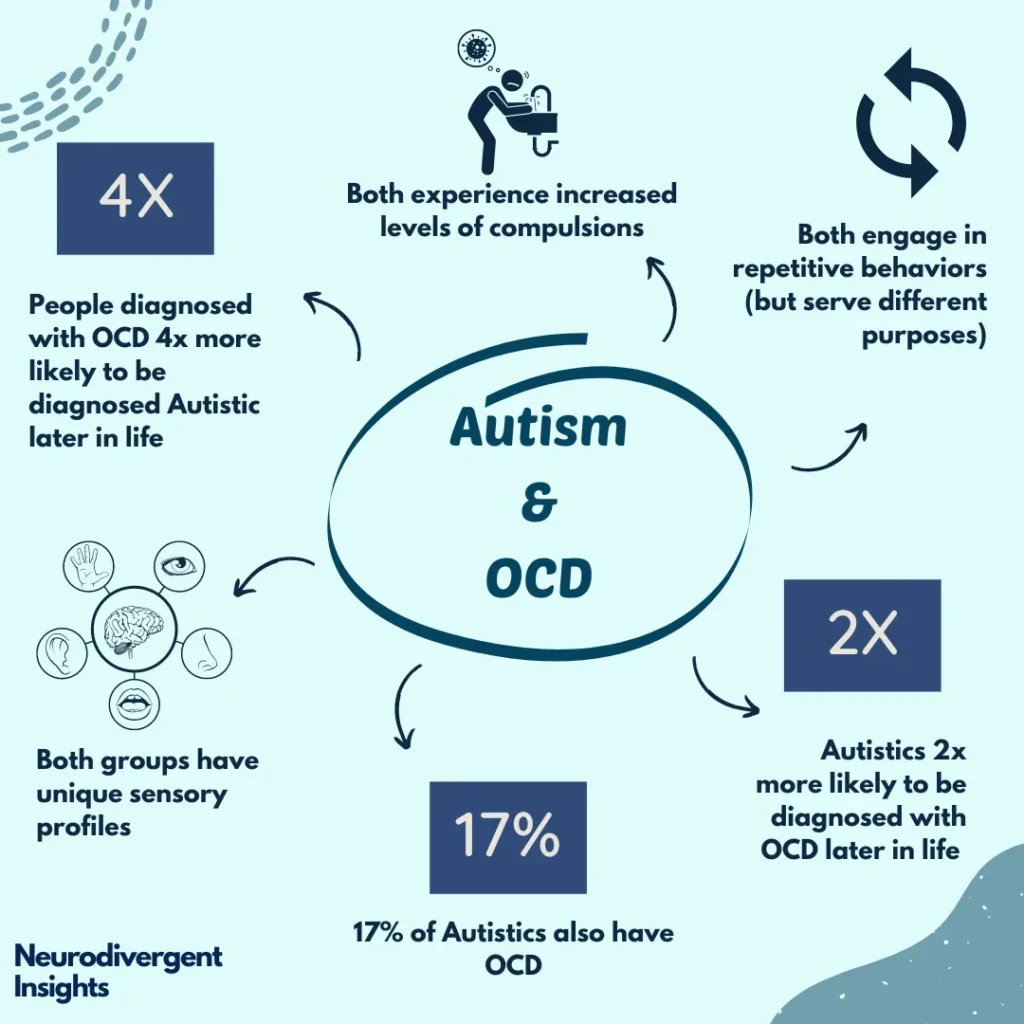

As I progressed through middle school and high school, my OCD became more internalized and focused on religious rituals, making it harder for others to notice. Given my history with OCD, it was no surprise to me when I learned that individuals diagnosed with OCD are four times more likely to receive an Autism diagnosis later in life. OCD often co-occurs with other conditions, as evidenced by one study showing 69% of individuals with OCD having another condition alongside it. Similarly, Autism is rarely experienced in isolation, with a recent study revealing that 77.7% of Autistic children had at least one additional mental health condition. Therefore, it’s not uncommon for Autism and OCD to frequently coexist.

In this blog post, we will:

Explore the relationship between Autism and OCD

Dive into the prevalence rates

Consider the implications of co-occurrence

Address the unique considerations when treating Autistic people with OCD.

For a more in-depth look into the research on OCD and Autism and how to spot the difference, I recommend reviewing my Misdiagnosis Monday Venn diagram “OCD vs. Autism.”

The Overlap Between Autism and OCD: Understanding the Prevalence Rates

Autism and OCD commonly intersect. When these two intersect, it can create a lot of complications! Research has shown a high degree of overlap between Autism and OCD. Autistic people are more likely to develop OCD later in life, while those with OCD are more likely to be diagnosed as Autistic later in life. Here is a review of some of the studies that have looked at overlapping autism and OCD:

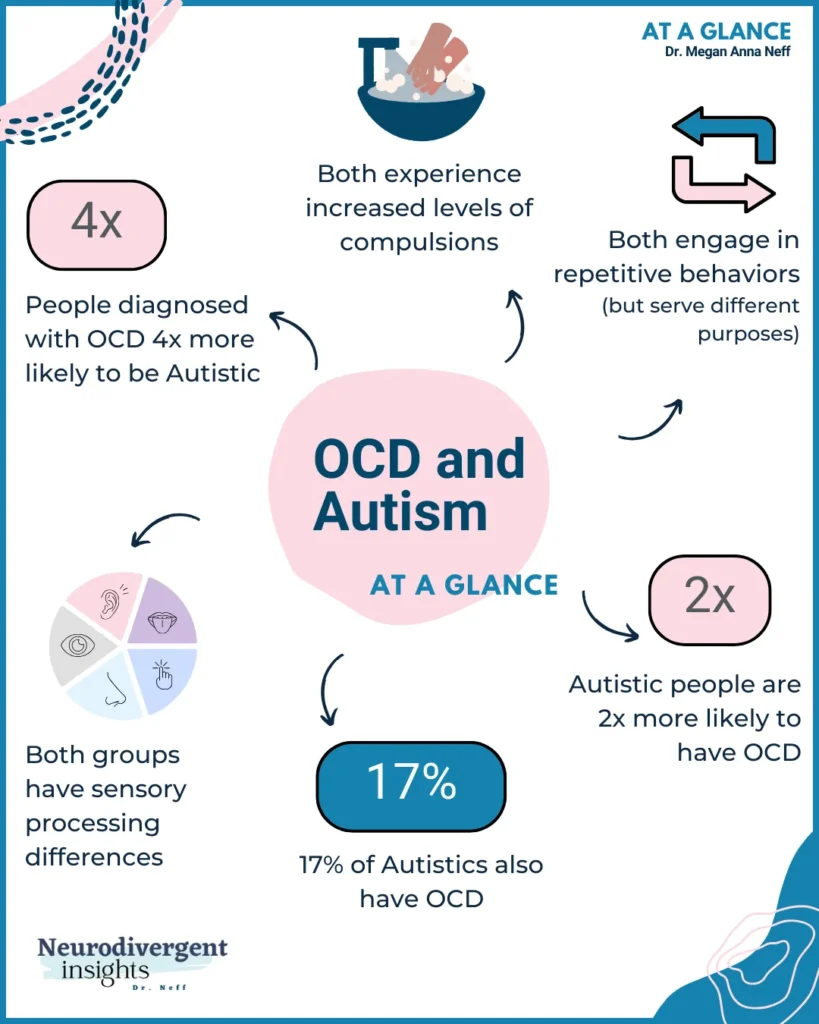

A population-based study in Denmark found that Autistic people were 2x more likely to be diagnosed with OCD later in life. In contrast, individuals diagnosed with OCD were 4x more likely to be diagnosed with Autism later in life (Meier et al., 2015)!

Other studies have shown similarly high levels of overlap, with 47% of individuals with OCD having clinically significant Autistic traits and 27.8% meeting full diagnostic criteria for Autism (Wikramanayake et al., 2018). It is speculated that a larger proportion of people with OCD may be undiagnosed Autistic people.

Anxiety disorders, including OCD, are pervasive among Autistic people. Approximately 84% of Autistic people have some form of anxiety disorder (Postorino et al., 2017), and up to 17% of Autistic people have OCD specifically (Van Steensel et al., 2011).

Autism and OCD: Understanding the Overlapping Symptoms

When Autism intersects with OCD, it can create unique challenges. Autistic rituals and OCD compulsions can exacerbate one another, making it difficult to distinguish between them. Obsessions and sensory issues can collide and compound one another! Another complicating factor is that situational factors may reinforce OCD. For instance, if OCD interferes with going to school or social events, and if these situations are unpleasant for sensory reasons or other Autism related reasons, it can unconsciously reinforce the OCD.

Compulsions vs. Repetitive Restricted Behaviors

One of the trickiest pieces to tease out is the difference between compulsions and repetitive behaviors. To distinguish between Repetitive Restricted Behaviors (RRBs) and OCD compulsions, it’s essential to understand the personal subjective or inner experience. It is through understanding the purpose behind the behaviors that these two experiences are teased apart. RRBs often are self-soothing, and these behaviors do not serve a cause-effect purpose. On the other hand, OCD compulsions serve a specific purpose, such as reducing anxiety or distress caused by obsessive thoughts. While compulsions may temporarily ease anxiety (which can soothe the anxiety temporarily), these behaviors are often not self-soothing in their own right.

For example, in OCD, a person will engage in compulsive behavior for a specific function (washing hands to reduce the anxious feelings associated with contamination). Or in the example where I feared my parents would die if I didn’t say goodbye with my ritual.

Alternatively, the function of repetitive behaviors in the context of autism serves a less obvious function. For example, the person may wash their hands under water for a prolonged time. Not because they fear contamination but because they are fixated on the water, and the sensation is soothing. They may have a specific nighttime or morning routine or have a ritualized way of saying goodbye or hello. However, there aren’t the same cause-effect relationships. For example, if an Autistic person breaks their goodbye ritual, it isn’t accompanied by the anxiety their parents will die. However, it still will likely be accompanied by free-floating anxiety due to the routine disruption. Rouine provides a sense of what to expect and is soothing. Deviations from the routine cause free-floating anxiety (not due to a specific fear like when I feared my parents would die if I didn’t do the compulsion), but due to routine-disruption anxiety.

Sensory Processing Differences

Sensory processing issues are a trademark of autism. It is a less well-known part of OCD. Both autism and OCD come with unusual sensory processing. Experiences.

People with OCD are more intolerant of sensory stimuli, which can lead to ritualistic behavior (Hazen et al., 2008).

Sensory processing sensitivities (particularly oral and tactile hypersensitivity) have been linked with OCD symptoms later in life (Dar et al. 2012).

Unusual sensory interests may be key to understanding the link between Autism and OCD. This may suggest different pathways to compulsive behaviors (sensory-based vs. cognitive-based pathways, etc.) (Ruzzano et al., 2015). For Autistic people with OCD, our sensory issues may become heightened (especially in the case of OCD contamination obsessions).

Treating Co-Occurring Autism and OCD: Unique Considerations

Treating Autistic people with co-occurring OCD can be challenging. Traditional OCD treatment approaches, such as exposure and response prevention (ERP), often need to be adapted to consider the needs of Autistic people. Here are some adaptations that can be made:

✦ Addressing sensory processing issues

✦ Developing coping strategies that take into account an individual’s Autism-related strengths

✦ Incorporating special interests and concrete metaphors in building anxiety thermometers and hierarchies

✦ Including visualizations into psycho-education

✦ Drawing upon more close-ended questions to identify anxiety triggers and experiences

✦ Addressing alexithymia and difficulty differentiating subtle emotions and interoception struggles before initiating exposure-based work

✦ Lengthening treatment and taking a slower approach to exposure-based work

To learn more about adapting traditional Exposure and Response Treatment (ERP) for autism, check out OCD for Autism which provides a guide for clinicians on how to adapt ERP for Autistic clients.

Key Takeaways: Understanding and Treating Autism and OCD

To summarize, while Autism and OCD are distinct, there is a high prevalence of co-occurring Autism and OCD. The needs of Autistic people must be considered when designing treatment plans for co-occurring OCD. Overall, understanding the relationship between Autism and OCD can help healthcare professionals provide more effective treatment to Autistic people with OCD.

By considering the specific needs and experiences of Autistic people with OCD, healthcare professionals can develop individualized treatment plans that consider our strengths, challenges, and sensory processing needs.

Some ways of adapting OCD treatment include: Utilizing sensory integration therapy, developing coping strategies that consider Autism-related strengths, and adapting traditional OCD treatment approaches to accommodate our needs are all important considerations. Communication differences, such as literal and concrete language use, should also be considered and adapted for when using CBT for OCD. Adapting traditional OCD treatments can ultimately lead to improved quality of life for Autistic individuals with co-occurring Autism and OCD.

Resources/Treatment

✦ For children/teens with OCD: What To Do When Your Brain Gets Stuck is my current favorite. If you’re looking for specific activities, Standing up to OCD Workbook for Kids: 40 Activities to Stop Unwanted Thoughts.

✦ For clinicians looking to learn how to adapt OCD treatment for their Autistic clients, OCD for Autism is one of the first resources out there for how to adapt OCD to work more efficiently with the Autistic profile.

*If you are interested in learning more about ADHD and OCD, you can check out this ADHD infographic over here.

Citations

Dar R, Kahn DT, Carmeli R. The relationship between sensory processing, childhood rituals and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2012 Mar;43(1):679-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.008. Epub 2011 Sep 14. PMID: 21963890.

Hazen EP, Reichert EL, Piacentini JC, Miguel EC, do Rosario MC, Pauls D, Geller DA. Case series: Sensory intolerance as a primary symptom of pediatric OCD. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008 Oct-Dec;20(4):199-203. doi: 10.1080/10401230802437365. PMID: 19034751; PMCID: PMC3736727.

Meier SM, Petersen L, Schendel DE, Mattheisen M, Mortensen PB, Mors O. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorders: Longitudinal and Offspring Risk. PLoS One. 2015 Nov 11;10(11):e0141703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141703. PMID: 26558765; PMCID: PMC4641696.

Postorino V, Kerns CM, Vivanti G, Bradshaw J, Siracusano M, Mazzone L. Anxiety Disorders and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017 Oct 30;19(12):92. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0846-y. PMID: 29082426; PMCID: PMC5846200.

Ruzzano L, Borsboom D, Geurts HM. Repetitive behaviors in autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder: new perspectives from a network analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015 Jan;45(1):192-202. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2204-9. PMID: 25149176.

Sharma E, Sharma LP, Balachander S, Lin B, Manohar H, Khanna P, Lu C, Garg K, Thomas TL, Au ACL, Selles RR, Højgaard DRMA, Skarphedinsson G, Stewart SE. Comorbidities in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Across the Lifespan: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021 Nov 11;12:703701. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.703701. PMID: 34858219; PMCID: PMC8631971.

Wikramanayake WNM, Mandy W, Shahper S, Kaur S, Kolli S, Osman S, Reid J, Jefferies-Sewell K, Fineberg NA. Autism spectrum disorders in adult outpatients with obsessive compulsive disorder in the UK. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2018 Mar;22(1):54-62. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2017.1354029. Epub 2017 Aug 11. PMID: 28705096.