How Connected are Autism and Anxiety, and Does it Impact Autistics More?

Earlier this year, I found myself seeking some much-needed sunshine on a trip to California with my youngest child. One day, as we enjoyed the small backyard pool, I noticed electrical wires overhead. A stormy scenario unfolded in my mind: the wires breaking during a storm, snapping and landing in the water, threatening to electrocute us both. The scene played out so vividly that it was like watching a movie. As the wind began to pick up, I instinctively told my child, “I think we should get out of the pool.” Realizing the source of my fear, I added, “I think that’s anxiety talking.” Familiar with the contours of anxiety themselves, my child agreed, “Yes, that’s the anxiety.”

My brain is inherently creative—it thrives on “what ifs.” This kind of creativity is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it has fueled the creation of my business, Neurodivergent Insights, by channeling my curiosity and creativity into productive pursuits. On the other hand, it means I’m frequently bombarded by vivid, often catastrophic scenarios.* This ongoing internal melodrama of anxiety isn’t unique to me; it’s a shared experience among many Autistic people.

In exploring the Autistic experience, it becomes clear that we are more prone to anxiety and experience it more intensely than our neurotypical peers. This article aims to delve into the reasons behind this heightened vulnerability and discuss the impact.

Autism and Anxiety

Anxiety is notably prevalent among Autistic people and stands as one of the most common psychiatric conditions among us, particularly among those without co-occurring intellectual disabilities (Casa & Mazurek, 2015; Nimmo-Smith et al., 2020). A striking 69% of Autistic children aged 9-13 were found to have clinically significant anxiety, according to a 2021 study (Kerns et al., 2021). However, prevalence rates of anxiety among Autistic people vary widely in research, ranging from 42% to 79% across different ages.

In Autistic adults, recent studies have found that about 27% currently experience some form of anxiety disorder, while the lifetime prevalence—meaning the chance of having an anxiety disorder at any point in their lives—reaches about 42% (Hollocks et al., 2019).

For Autistic children, the rate is higher, with 49% having an anxiety diagnosis. Intriguingly, 96% of these children, particularly those who are highly masking and verbally fluent without intellectual differences, qualified for at least two anxiety disorders. The onset of anxiety tends to occur at a younger age in Autistic children, but the research results are mixed regarding the influence of gender and whether anxiety increases with age. However, there is consistent evidence that higher IQ in Autistic children is associated with increased rates of anxiety.

Why Are Autistic People More Prone to Anxiety?

Autistic people often experience anxiety more intensely and differently than our neurotypical peers. This heightened susceptibility can be attributed to several unique factors.

First, many Autistic people encounter “atypical anxiety”, which includes things like overwhelm, fear of change, sensory-based anxiety, and other anxiety-like experiences that extend beyond the conventional symptoms of anxiety. For a deeper exploration of atypical versus typical anxiety, you can read more on this topic here.

Research indicates a genetic predisposition among Autistic people and their families towards anxiety disorders, suggesting a hereditary component (Nimmo-Smith et al., 2020). Additionally, Autistic nervous systems tend to be less flexible, making them more sensitive and prone to shifting into states of hyperarousal (overdrive) or hypoarousal (shutdown), which are often experienced as anxiety.

Navigating a world designed for neurotypical individuals adds another layer of complexity and increases the potential for anxiety. Autistic people frequently face challenges such as deciphering allistic social-communication patterns, managing sensory differences (whether overload or under-stimulation), and overcoming executive functioning hurdles. The lack of understanding and empathy from others can exacerbate these difficulties, contributing to increased daily stress and anxiety.

The Impact of Masking on Anxiety

The act of masking—or camouflaging Autistic traits to align with neurotypical expectations—also significantly contributes to anxiety in Autistic people. This phenomenon is especially prominent among those with advanced verbal abilities. Individuals with greater verbal skills often experience heightened levels of anxiety. This correlation may stem from the increased expectations to utilize these verbal skills to navigate complex social landscapes more effectively.

For Autistic people, possessing high verbal abilities can amplify the pressure to perform socially, consistently mask Autistic traits, and adhere to neurotypical standards, all of which can intensify anxiety. These enhanced verbal skills can make individuals more attuned to social nuances and the potential repercussions of social errors, thus increasing their vigilance and anxiety concerning social interactions.

Increased verbal communication in Autistic individuals often indicates a higher tendency to mask. This ongoing adjustment demands vigilant self-monitoring and adaptation across a variety of social interactions. When masking, Autistic people meticulously manage their body posture, facial expressions, tone of voice, and choice of words to conform to the expected social norms.

This process extends beyond superficial changes in behaviors; it involves a profound, psychological effort to avert social missteps, react ‘correctly’ to perceived judgments, and continuously revise behavioral strategies to prevent repeating errors. Such relentless self-monitoring and its mental burden naturally escalate anxiety, making everyday interactions a source of significant stress. Over time, this sustained effort to conform to societal norms can perpetuate anxiety experiences and contribute to the development of anxiety disorders.

Social Anxiety and Autism

Social anxiety is notably prevalent among Autistic people. Given its prevalence, I recommend that when social anxiety is detected, screening for autism should also be considered. Studies indicate that up to 50% of Autistic people experience social anxiety (Maddox & White, 2015; Spain et al., 2016).

The high rates of social anxiety among Autistic people can likely be attributed to several key factors. First, navigating communication differences between neurotypes presents considerable challenges. Autistic individuals often perceive and process social cues differently than their allistic peers, which can lead to misunderstandings and increased anxiety in social situations.

Additionally, the effort required for Autistic people to engage successfully in social interactions with allistic people can be substantial. This often involves adapting their natural communication styles and behaviors to fit allistic expectations, a process that can be both exhausting and anxiety-inducing.

Another contributing factor is the need to manage unpredictable environments. Social settings often vary greatly in terms of sensory inputs and social dynamics, which can be particularly difficult for Autistic people who do best with predictability and routine. The need to adjust frequently to new social rules and settings can exacerbate feelings of anxiety.

Anxiety is an Epidemic

Beyond the Autistic experience, anxiety in general is on the rise. Anxiety disorders overall are the most common mental health disorders. They cover the whole life span and 11 is the average age of onset.

Before the pandemic, about 8% of teenagers between the ages of 13 and 18 experienced anxiety. However, research conducted after the pandemic shows that this number has increased to include approximately one-third of all teenagers.

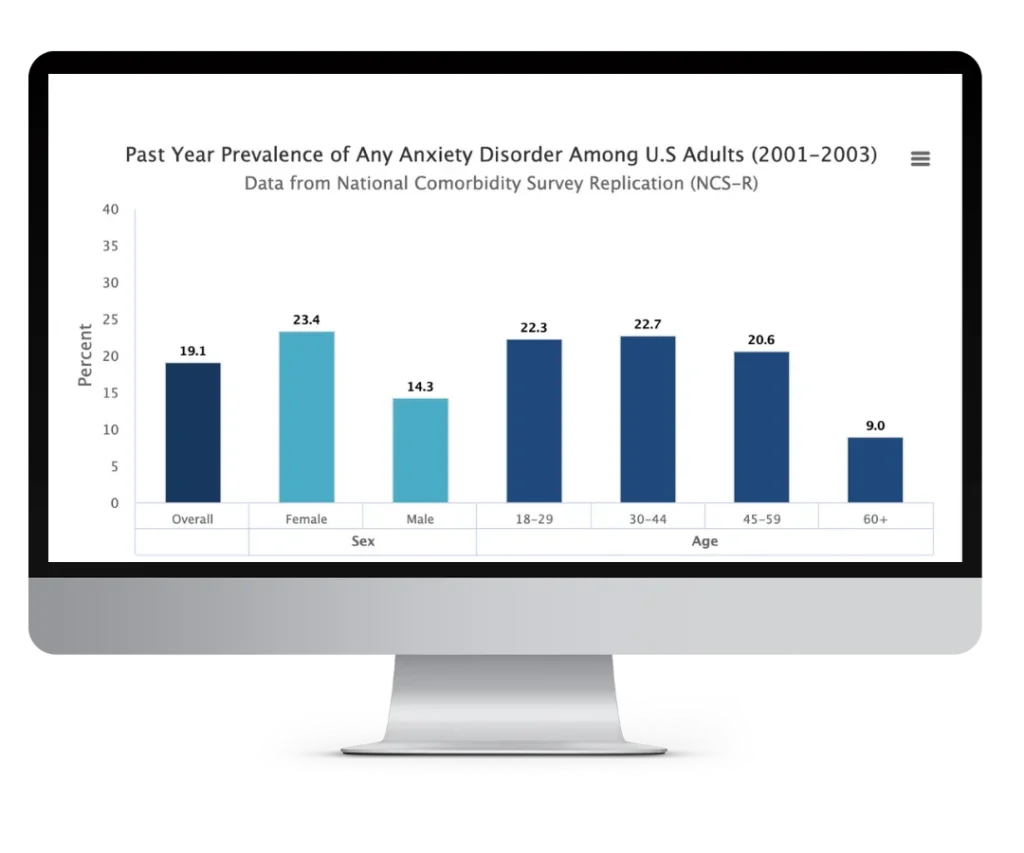

Adult anxiety has increased as well. Early 2000 studies found that 19% of adults experienced an anxiety disorder in a given year, and we know rates have significantly increased since 2000.

Anxiety rates are high across the board and continue to rise. It remains one of the most common mental health conditions and is also one of the easiest to treat—provided individuals seek help (Dalton, 2023).

What Constitutes an Anxiety Disorder?

Anxiety manifests through a variety of physical and cognitive symptoms, which can vary significantly from person to person. Physically, individuals may experience a racing heart, tense muscles, shaky hands, or a restless mind. Some might encounter an upset stomach, lose their appetite, feel lightheaded, or even fear they are about to faint. Others may have difficulty breathing or experience sensations that mimic a heart attack.

Cognitively, anxiety often presents as persistent worry, rumination, or catastrophic thinking, where individuals anticipate the worst possible outcomes in various scenarios. These mental symptoms can dominate a person’s thinking, making it difficult to focus on anything else.

Adaptive Vs. Disordered Anxiety

Anxiety is a natural human response designed to protect us by heightening our awareness and readiness to face potential threats. This “adaptive anxiety” can be beneficial, sharpening our senses and preparing us for challenges, such as performing in a high-stakes environment or reacting quickly to avoid an accident. In these situations, anxiety is proportionate to the situation and helps improve performance or ensure safety.

However, when anxiety becomes disproportionate and persistently interferes with our ability to function in daily life, it transitions into disordered anxiety. Disordered anxiety is characterized not just by its intensity but by its persistence and the significant distress it causes.

For example, while adaptive anxiety might cause temporary nervousness during a public speech, disordered anxiety could lead to overwhelming fear weeks before the event, affecting a person’s ability to prepare or even prompting them to avoid the situation entirely.

The distinction between adaptive and disordered anxiety hinges on functionality and proportionality. Disordered anxiety is marked by its chronic nature and its tendency to disrupt normal activities and emotional well-being, even in ordinary circumstances. This could mean that a person, while able to go to work, might struggle significantly with daily interactions or decision-making due to persistent worry or fear.

This level of anxiety emphasizes that, unlike adaptive anxiety, disordered anxiety lacks any protective or beneficial role. Instead, it causes significant harm and suffering.

Understanding this distinction is crucial for recognizing when anxiety has crossed the line from being a helpful, evolutionary alert system to a debilitating disorder that is causing harm.

Types of Anxiety Disorders

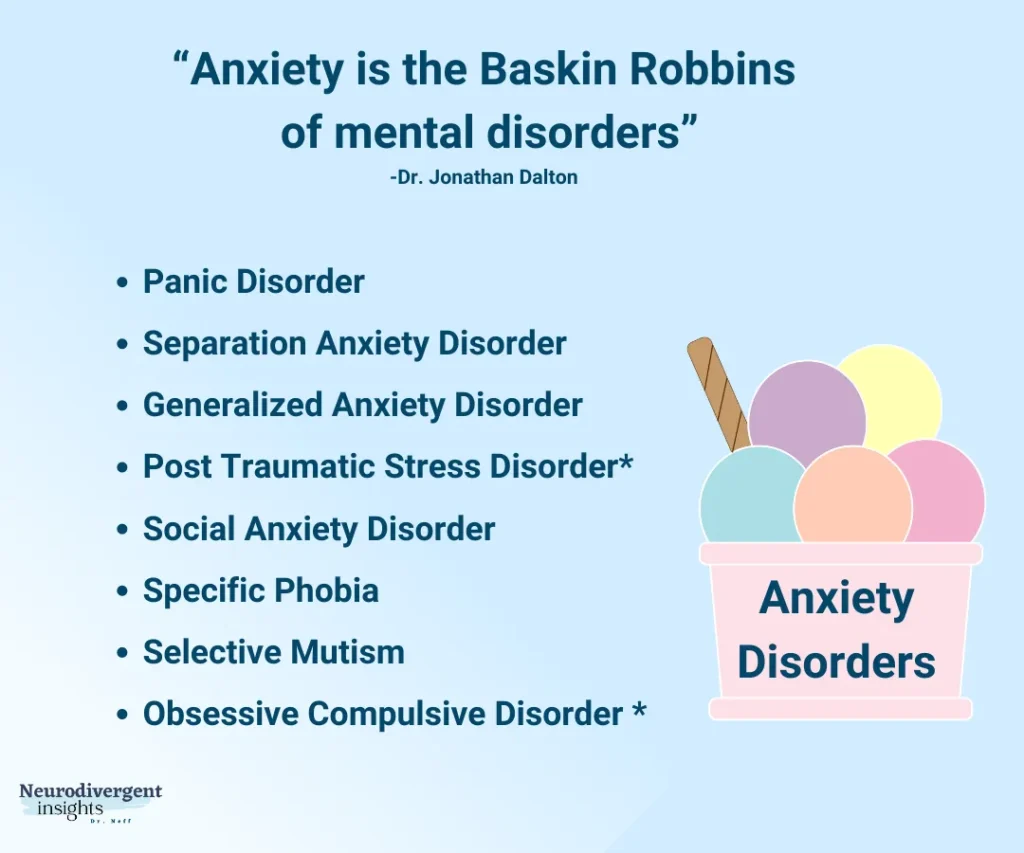

As Dr. Jonathan Dalton notes, anxiety is the “Baskin Robbins” of mental disorders—it comes in many shapes and sizes!

Included in the anxiety disorders category are:

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Specific Phobia

Social Anxiety Disorder

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)*

Panic Disorder

Separation Anxiety Disorder

Selective Mutism

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)*

*Note: Although OCD and PTSD are no longer classified strictly as anxiety disorders in the latest diagnostic manuals, they are often included due to their overlapping features with anxiety disorders.

Autistic people experience all of these at higher rates but the most common in Autistic children and teens are obsessive compulsive disorder, specific phobia, and social anxiety. Generalized anxiety disorder becomes more common in the Autistic individual with age.

Why Treating Anxiety in Autism is Important

Addressing anxiety is crucial for Autistic people and those within the broader neurodivergent community. Anxiety isn’t just an isolated issue; its importance lies in the widespread and debilitating effects it can have if not treated. Untreated anxiety can severely disrupt daily life, potentially leading to situations where a person’s life tends to shrink—becoming smaller and smaller. They might avoid school, work, or even stepping outside their home. Moreover, there is a well-documented link between untreated anxiety disorders and higher rates of substance abuse. Anxiety, when left untreated, can also evolve and metastasize into depression, which is typically more complex and challenging to treat (Dalton, 2023).

For Autistic people, the stakes are even higher. Anxiety amplifies the already-higher challenges of daily activities, contributing significantly to exhaustion. The hyperarousal associated with anxiety can increase the likelihood of meltdowns, as it intensifies the already overwhelming sensory environments that many Autistic people navigate. Additionally, anxiety can be a contributing factor to Autistic burnout, adding another layer of difficulty to interactions in a predominantly neurotypical world.

Treating anxiety in Autistic people goes beyond just addressing a mental health condition. It’s really about helping people reclaim their everyday lives and improving their overall quality of life. When anxiety is managed effectively, it can pave the way for more stable daily routines, richer social interactions, and a more satisfying life overall. That’s why it’s so important to prioritize interventions that are both prompt and tailored to the distinct needs of Autistic people.

Conclusion

As we’ve seen, anxiety is quite prevalent among the Autistic community and can wreak havoc on our lives. Throughout this blog post series, you’ll discover how neurodivergent anxiety differs significantly from neurotypical anxiety and why it requires specialized approaches to treatment. Stay tuned for our next installment on Autistic anxiety, coming next week, where we’ll dive deeper into these differences and strategies for management.

Interested in learning even more? Join us for a workshop with Dr. Jonathan Dalton, where we discuss these topics in greater detail. You can purchase the recording here.

Footnotes

*The dual nature of “what if” thinking as both a creative strength and a source of anxiety is discussed by Dr. Dalton in his talk “Understanding Anxiety: A Strength-Based Perspective.”

References

Dalton, J. (2023) Understanding anxiety: A strength-based perspective. [Presentation]. Neurodivergent Insights Masterclass.

Nimmo-Smith, V., Heuvelman, H., Dalman, C., Lundberg, M., Idring, S., Carpenter, P., … & Magnusson, C. (2020). Anxiety Disorders in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Population-Based Study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(1), 308-318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04234-3

Vasa, R. A., & Mazurek, M. O. (2015). An update on anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28(2), 83-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000133

Kent, R., & Simonoff, E. (2017). Prevalence of anxiety in autism spectrum disorders. In Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (pp. 5-32).

Kerns C.M., Winder-Patel B., Iosif A.M., Nordahl C.W., Heath B., Solomon M., Amaral D.G. Clinically significant anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder and varied intellectual functioning [published correction appears online ahead of print, J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol, Mar 27, 2020] J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2021;50:780–795.

Hollocks, M. J., Lerh, J. W., Magiati, I., Meiser-Stedman, R., & Brugha, T. S. (2019). Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 49(4), 559-572. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718002283

Maddox, B. B., Miyazaki, Y., & White, S. W. (2016). Long-term effects of CBT on social impairment in adolescents with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1-11.

Spain, D., Blainey, S. H., & Vaillancourt, K. (2017). Group cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for social interaction anxiety in adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 41, 20-30.