Navigating the complex landscape of mental health can be challenging, especially when identifying conditions with overlapping symptoms. Bipolar is one of those conditions with a complicated clinical picture, presenting symptoms that can mimic those of Borderline Personality Disorder or ADHD. Moreover, even within its own spectrum, distinguishing between Bipolar I and Bipolar II remains puzzling. Adding to this complexity is the high incidence of co-occurring conditions such as autism and ADHD, which further blurs diagnostic lines.

In an effort to clarify this complexity, I’ve included Bipolar I and Bipolar II in my “DSM in Pictures” series. This article specifically addresses the DSM-5 criteria for Bipolar I Disorder. The DSM-5 serves as the definitive guidebook for mental health professionals, classifying Bipolar I Disorder within a structured framework that aids in understanding these conditions. It’s also important to note that many providers refer to the ICD-11, which offers criteria similar to the DSM-5 for diagnosing this disorder.

Jump to ....

Types of Bipolar Disorders

Bipolar disorders encompass a range of conditions as described in the DSM-5 that cause extreme fluctuations in a person’s mood, energy, and ability to function. These conditions impact daily living substantially. The term “bipolar” reflects the person’s experience of shifting between two emotional poles—highs and lows—with very little warning.

Categories of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorders are primarily categorized into three main types:

Bipolar I Disorder: Characterized by full manic episodes that include an intoxicating rush of euphoria and boundless energy, leading to both creative surges and impulsive behaviors. Depressive episodes may occur, bringing profound sadness and a disinterest in previously enjoyed activities, although their presence is not required for a diagnosis.

Bipolar II Disorder: Identified by patterns of longer-lasting depressive episodes and hypomania, but without the full manic episodes seen in Bipolar I. In contrast to Bipolar I, a diagnosis of Bipolar II requires the presence of a depressive episode.

Cyclothymic Disorder: Involves fluctuations between milder depressive symptoms and hypomania, with symptoms persisting for at least two years. (NIMH)

The Episodic Nature of Bipolar Disorders

Bipolar disorder is episodic, meaning individuals will experience symptomatic periods interspersed with stable phases which are often referred to as euthymia. The mood cycles can vary greatly—some people may experience rapid cycling, while others have more distinct and prolonged phases. Mixed episodes featuring characteristics of both mania and depression can also occur.

Prevalence and Impact

Current figures suggest that bipolar spectrum disorders affect around 2.4% of people worldwide (Merikangas et al., 2011, Rowland et al., 2018 ). In the U.S., it’s estimated that 2.8% of adults have Bipolar and around 4.4% of the population will experience it at some point in their life. (NIMH).

Bipolar disorder substantially compromises both mental and physical health, severely impacting life quality. Recognized as one of the most life-threatening mental health conditions, it reduces the life expectancy of those diagnosed by 9 to 13 years compared to the general population. Complicating matters further, it takes 10 years on average from the onset of first symptoms to achieve a diagnosis (Shen, 2018).

Age of Onset

Symptoms typically first emerge during adolescence or early adulthood; however, there is often a significant delay between the initial appearance of symptoms and the formal diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

The teenage years are marked by significant emotional and hormonal changes, complicating the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. During this period, it can be challenging to distinguish between the normal range of adolescent behaviors and the more pronounced mood fluctuations characteristic of bipolar disorder. While there has been an increase in the recognition of bipolar disorder in younger individuals, this trend is not without controversy. The main challenge lies in differentiating between typical adolescent mood variability and the distinct mood instability associated with bipolar disorder.

DSM 5 Bipolar 1 Disorder Criteria

Bipolar I Disorder

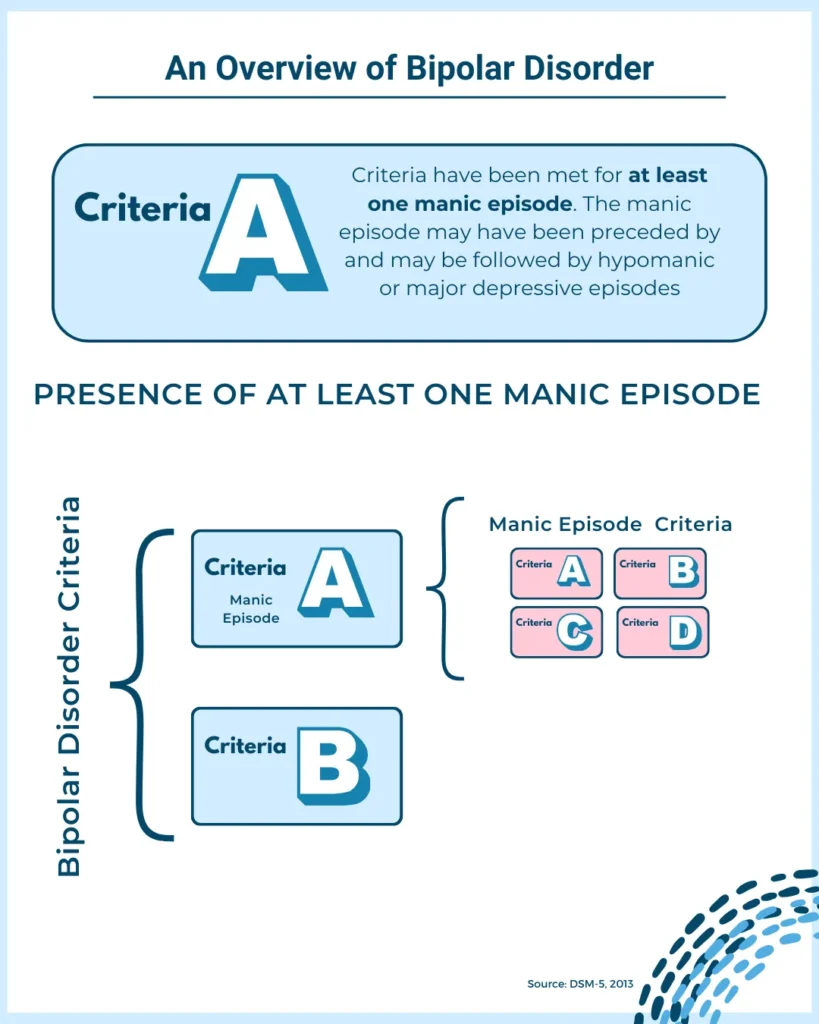

To be diagnosed with Bipolar I Disorder, an individual must meet the first and essential criterion known as Criteria A: the presence of at least one manic episode. This manic episode may occur independently or may precede or follow hypomanic or major depressive episodes; however, the occurrence of hypomanic or depressive episodes is not required for a diagnosis of Bipolar I Disorder.

What is a Manic Episode?

During manic phases, individuals with Bipolar I Disorder may experience an intoxicating high, characterized by feelings of euphoria and boundless energy. This heightened state can lead to creative surges and restless impulsivity.

Diagnostic Criteria for a Manic Episode

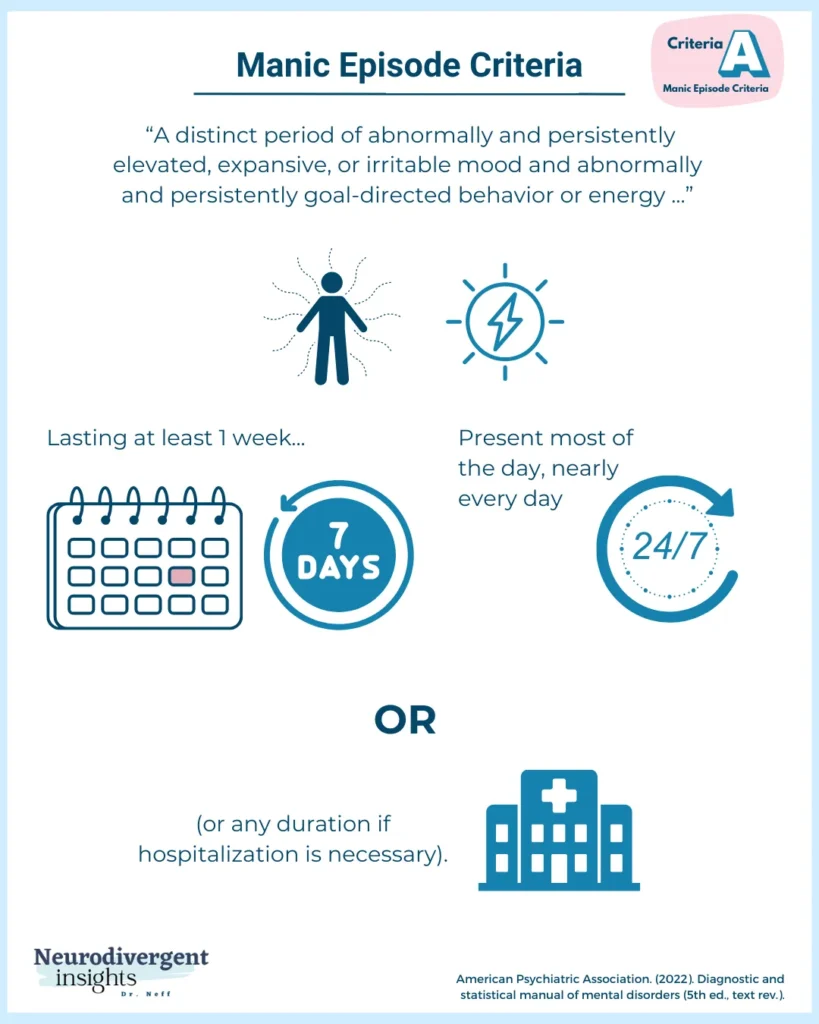

A manic episode is defined as a distinct period of abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood accompanied by increased activity or energy. The mood disturbances are so significant that they markedly disrupt the individual’s usual behavior and impair social or occupational functioning. These episodes typically last for at least one week, or less if hospitalization is required.

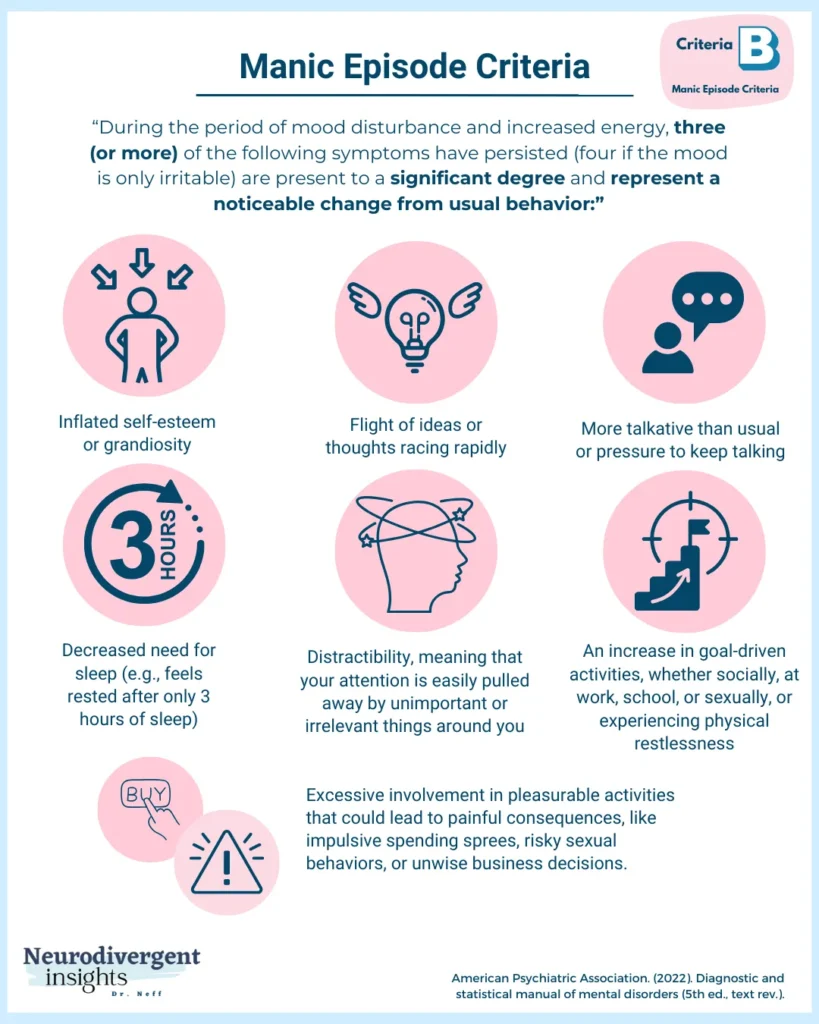

To meet the diagnostic criteria, the individual must exhibit at least three of the following symptoms during the episode (or four if the mood is predominantly irritable):

Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep)

More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking

Flight of ideas or the subjective experience that thoughts are racing

Easily distracted (i.e., attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant external stimuli)

Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or sexually) or physical restlessness

Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments) [NHS]

*During a manic episode a person may also experience psychotic symptoms, marked by a disconnection from reality. This can include hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that aren’t present) and delusions (holding strong beliefs that are not based in reality). Psychosis is present about 50% of the time in manic episodes (Keck et al., 2003).

Additional Considerations for Diagnosing a Manic Episode

For a manic episode to be diagnosed, the following criteria must also be met:

Persistence of Symptoms: The symptoms must be present most of the day nearly every day during the episode.

Deviation from Normal Behavior: The behavior must represent a noticeable departure from the individual’s normal behavior.

Severity: The mood disturbance must be severe enough to cause significant impairment in social or occupational functioning or necessitate hospitalization. If psychotic features are present or hospitalization is required, the episode is considered severe.

Exclusion of Other Factors: The symptoms must not be attributable to the physiological effects of substances (e.g., drug abuse, medication) or another medical condition.

Subjective Experience of Time During Mania

When people experience a manic episode their perception of time actually speeds up. So while it may seem to others that they are talking rapidly; their own perception is that others may be talking slowly. So the presence of mania actually influences how time itself is perceived and experienced! This can seem as if the world around them is frustratingly slow and sluggish, contributing to feelings of overwhelm and irritation (Northoff et al., 2018).

Impact on Daily Functioning

Mania profoundly affects daily functioning. Despite a surge in energy and heightened activity levels, the ability to manage day-to-day tasks is significantly impaired. This can disrupt personal relationships, work responsibilities, and overall quality of life. Without appropriate treatment, a manic episode can last anywhere from a week to several months, posing substantial long-term challenges in both personal and professional domains. What makes a manic episode distinct from a hypomanic episode is the disabling impact of the former.

Psychosis and Bipolar 1

Navigating bipolar disorder often involves confronting additional complexities, one of the most formidable being psychosis. This condition layers on significant challenges, with more than half of individuals with Bipolar I Disorder experiencing psychosis at some point. Psychotic symptoms, which include delusions and, less frequently, hallucinations are particularly pronounced during manic or mixed episodes. These episodes can profoundly distort reality, complicating interpersonal connections and making such interactions intensely challenging. While the presence of psychosis does not necessarily intensify the overall severity of bipolar disorder, it does introduce specific challenges, including:

Impaired insight into personal condition or behaviors

Increased agitation and hostility

Higher likelihood of hospitalization, particularly when psychotic features do not align with the mood state (mood-incongruent psychosis)

Despite these serious challenges, psychosis does not usually change the long-term overall course or outcomes of bipolar disorder. This underscores the complexity and diverse impacts of psychosis within the bipolar spectrum, emphasizing how crucial it is to tailor treatments carefully and to deeply understand the unique experiences of each person.

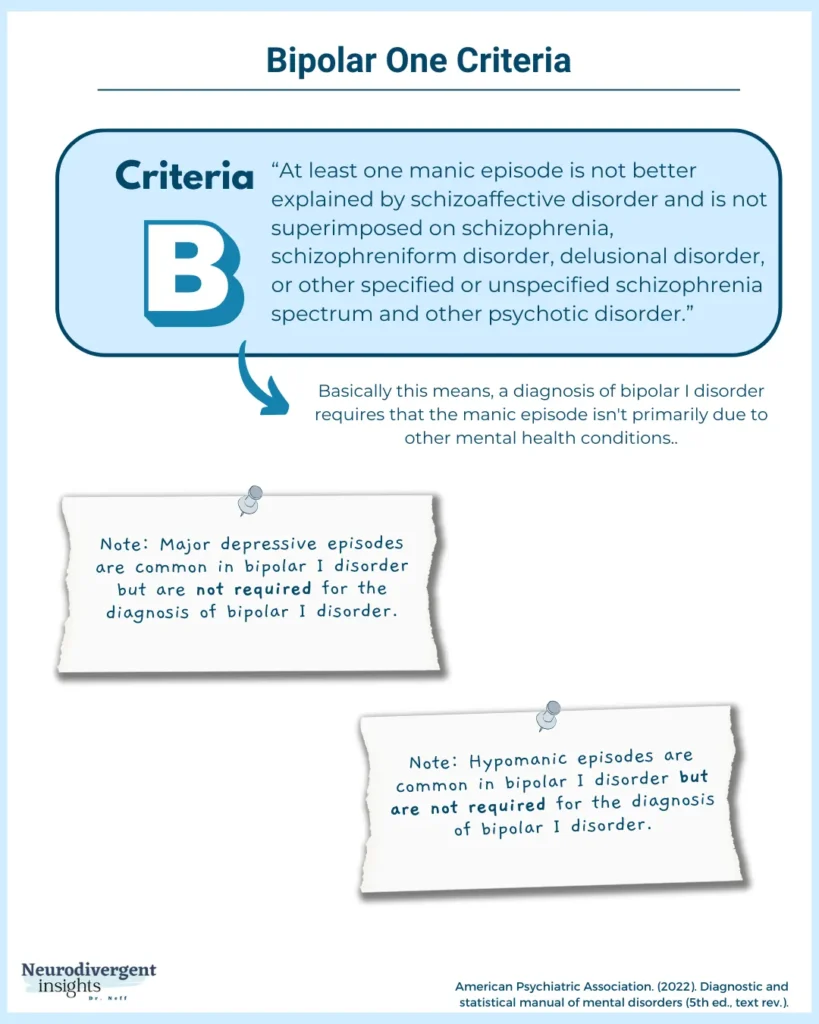

Exclusions: DSM Criteria B for Bipolar I Disorder

Criteria B for diagnosing Bipolar I Disorder specifies that the occurrence of at least one manic episode cannot be better explained by other mental health conditions, such as schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorders. This criterion ensures that the diagnosis is distinct and not confused with similar symptoms that might appear in these other disorders.

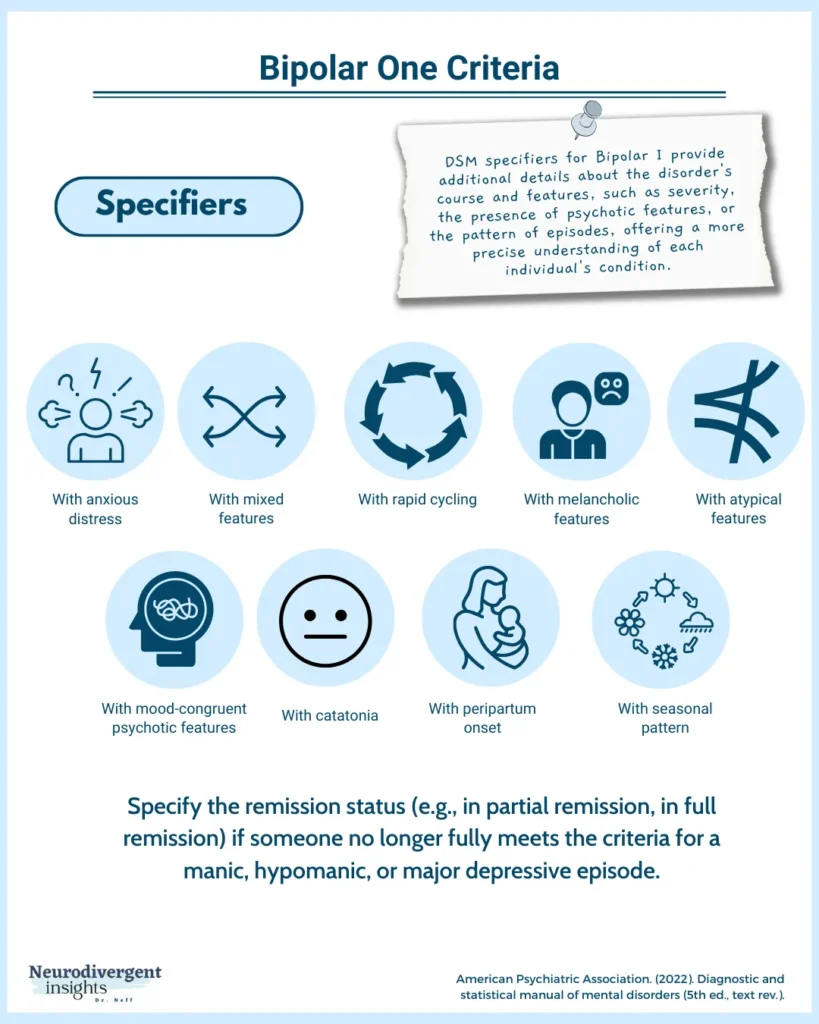

Specifiers

Specifiers provide additional details about the course and characteristics of Bipolar I Disorder, helping to tailor treatment plans and predict outcomes. Some of the key specifiers include:

With Anxious Distress: Indicates that significant anxiety or restlessness accompanies the mood episodes.

With Mixed Features: The individual experiences symptoms of both depression and mania/hypomania simultaneously.

With Rapid Cycling: Characterized by four or more mood episodes within a single year.

With Melancholic Features: Features severe anhedonia (loss of pleasure in nearly all activities) and profound despair.

With Atypical Features: Mood episodes exhibit atypical patterns

With Mood-Congruent Psychotic Features: Psychotic symptoms are consistent with the mood state, such as grandiosity during a manic episode or guilt during a depressive episode.

With Catatonia: Involves unusual motor behaviors that can range from complete lack of movement to excessive motor activity without purpose.

With Peripartum Onset: The onset of symptoms occurs during pregnancy or shortly after childbirth, significantly impacting the management and treatment approach.

Difference Between Bipolar 1 and 2 Disorder

The primary difference between Bipolar I and Bipolar II disorders lies in the severity of manic symptoms. Bipolar I Disorder involves at least one full-blown manic episode, characterized by extremely elevated or irritable moods that significantly impair functioning or require hospitalization, sometimes accompanied by psychotic symptoms such as delusions or hallucinations. These episodes are severe enough to significantly disrupt social and occupational functioning.

Conversely, Bipolar II Disorder is characterized by hypomanic episodes, which are less severe than full mania and do not typically necessitate hospitalization or cause significant functional disruption. However, Bipolar II also involves major depressive episodes, which are more prevalent and can be profoundly disabling. Hypomanic episodes, while milder, still mark a noticeable change from normal behavior but might be misunderstood as normal mood variations, leading to potential misdiagnosis.

This distinction is crucial as it affects treatment decisions and management of the disorder, with Bipolar II often involving longer periods of depression interspersed with shorter periods of hypomania.

Conclusion

Understanding Bipolar I Disorder involves recognizing the complexities of its symptoms and impacts. From the disabling nature of manic episodes to the subtleties of its diagnostic criteria, each aspect of Bipolar I presents unique challenges and demands specific approaches to treatment and management.

For those seeking a more visual and detailed exploration of Bipolar I Disorder, the “Bipolar 1 DSM in Pictures” series offers a visual look at these dynamics. The series is designed to provide a clearer understanding through visual aids and simplified explanations, making it a resource for both healthcare professionals and those experiencing Bipolar disorder. You can find the PDF here.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.).

Chakrabarti, S., & Singh, N. (2022). Psychotic symptoms in bipolar disorder and their impact on the illness: A systematic review. World journal of psychiatry, 12(9), 1204–1232. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i9.1204

Keck, P. E., Jr, McElroy, S. L., Havens, J. R., Altshuler, L. L., Nolen, W. A., Frye, M. A., Suppes, T., Denicoff, K. D., Kupka, R., Leverich, G. S., Rush, A. J., & Post, R. M. (2003). Psychosis in bipolar disorder: phenomenology and impact on morbidity and course of illness. Comprehensive psychiatry, 44(4), 263–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00089-0

Merikangas, K. R., Akiskal, H. S., Angst, J., Greenberg, P. E., Hirschfeld, R. M. A., Petukhova, M., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(5), 543. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543

Northoff, G., Magioncalda, P., Martino, M., Lee, H.-C., Tseng, Y.-C., Lane, T. (2018). Too fast or too slow? Time and neuronal variability in bipolar disorder—A combined theoretical and empirical investigation. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(1), 54–64.

Rowland, T. A., & Marwaha, S. (2018). Epidemiology and risk factors for bipolar disorder. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 8(9), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125318769235