Disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through these links, I will earn a commission at no extra cost to you.

Do you feel overwhelmed and anxious, like you’re constantly on edge and ready to fight or flee? This experience is all too familiar for those of us with an overactive fight or flight response, which is particularly common among neurodivergent individuals and those who have experienced trauma. You may already be familiar with the fight or flight response—a simplified term for how humans and many other animals respond to threats. The fight or flight response is a natural survival mechanism that helps us protect ourselves from danger, but when it’s constantly activated, it can lead to physical and emotional stress, difficulty sleeping, and other health problems.

During my 20s, I experienced an overactive fight or flight response, especially when my children were young and I wasn’t getting enough sleep. My body was frequently in a state of sympathetic dominance, which left me feeling overwhelmed and anxious. It wasn’t until I began my training to become a clinical psychologist that I learned about nervous system regulation and how to find greater balance in my body.

Learning about nervous system regulation had a profound impact on me, and it’s now one of my favorite topics to talk about. In this article, we’ll discuss how the fight or flight response is an evolutionary adaptation that helps us deal with immediate threats. However, in today’s world of chronic stressors, this response can become less helpful and more damaging to our health and well-being. We’ll also explore six practical ways to calm your fight or flight response, so you can find greater ease and resilience in your daily life.

What Is The Fight-or-Flight

Response?

The fight or flight response is a natural response to acute threats that prepares the body to react or retreat. Evolutionarily, this response made sense for early humans who lived outdoors and were more likely to encounter threats from predators.

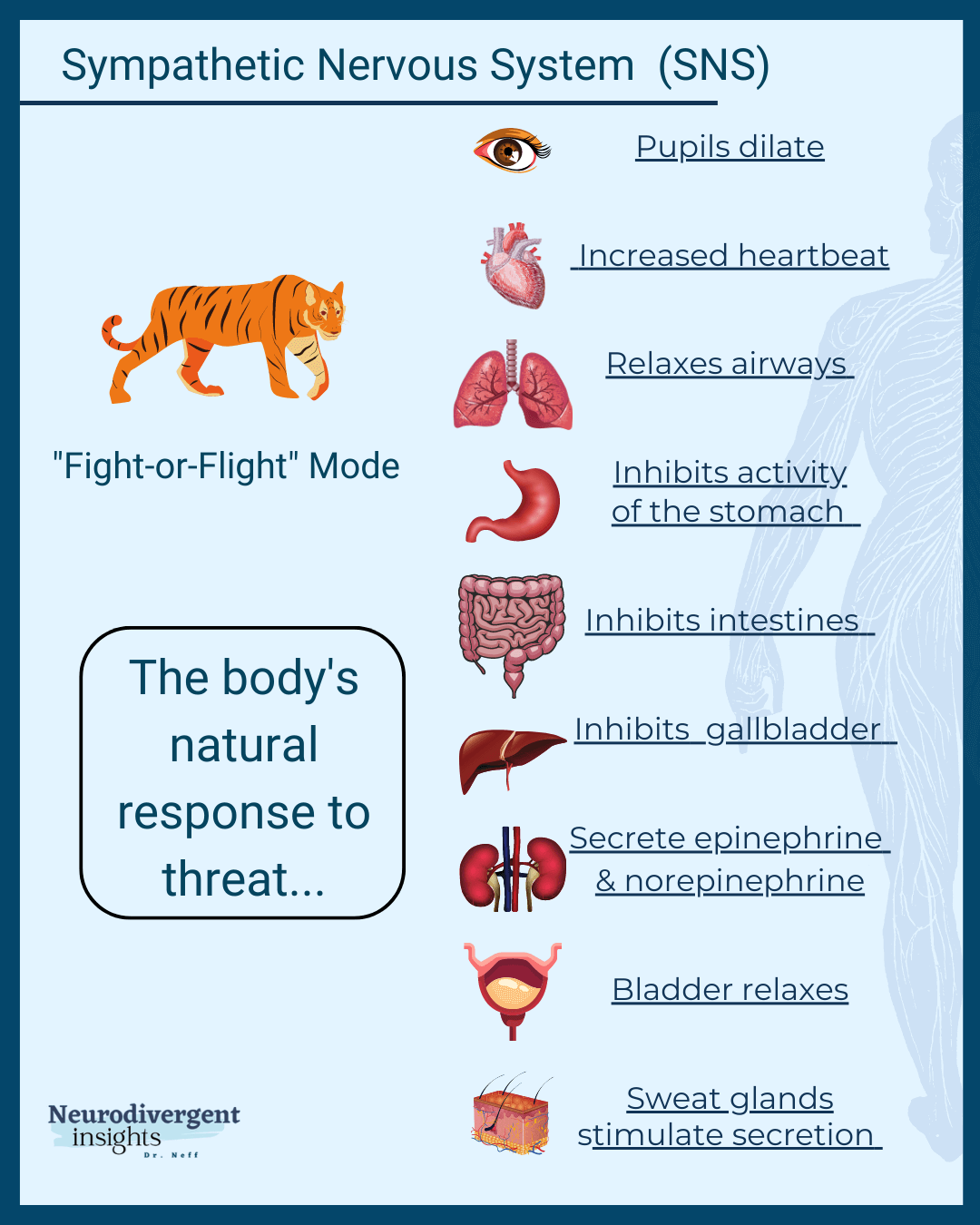

Stress hijacks our nervous systems in these moments. When we’re stressed, our bodies go into the hyper-alert mode, which triggers several physical changes all at once:

✦ Pupils dilate to take in more information

✦ Heart rate increases to pump blood to our muscles faster

✦ Cortisol and adrenaline increase to make us faster and stronger

✦ Digestive system slows to prioritize energy

As you can see, stress is a full-body experience! While these bodily changes can be helpful in situations where we need to react quickly to a threat, they can be less helpful in modern times. In the next section, we’ll explore why the fight or flight response can be problematic in our current society and what we can do to manage it.

How Do We Experience Fight or Flight in The Modern World?

Despite living in a modern society with fewer physical threats, our nervous systems haven’t evolved to keep up with the stressors of the 21st century. As a result, even minor stressors can activate the fight or flight response, preparing our bodies for action.

In today’s world, many perceived threats are not physical but rather cognitive. For example, job interviews, social media pressure, or even running late for a meeting can trigger the same physical response as being chased by a predator. This can lead to heightened sympathetic nervous system activity, causing symptoms of anxiety and making it difficult to manage stress effectively.

For instance, if you are about to give a speech in front of a room full of people, you may feel nervous. Your heart rate and breathing are likely increasing, and you may not feel like eating anything. Your body is preparing to fight or flee, even though it’s not a life-threatening situation.

While the fight or flight response is a natural and adaptive response that has helped us survive as a species, in modern times, this response can be more harmful than helpful. In the next section, we’ll discuss practical ways to calm the fight or flight response and help you manage stress more effectively.

6 Ways to Calm Your Fight or Flight Response

Stress is a full-body experience, which means we need to intervene at the body level to regulate and return to a state of balance. Here are six practices that can help to calm down the fight or flight response:

1. Deep Breathing

Methods for counteracting the fight or flight response generally involve actively doing the opposite of what your sympathetic nervous system automatically triggers. For example, while the sympathetic nervous system increases respiratory rate and breathing becomes shallow in times of stress, researchers have found that we can actively counteract the fight or flight response by taking slow, deep abdominal breaths (Perciavalle et al., 2017). Taking slow, deep abdominal breaths can counteract the fight or flight response by slowing down the respiratory rate and calming the nervous system.

2. Notice Patterns, Map Your Nervous System

Pay attention to when your fight or flight response is more active. This can help you become more aware of your own stress and anxiety levels and take proactive steps to manage them.

For example, maybe you notice that you are more likely to be on edge and jittery, or you may notice your breathing becomes more rapid or your thoughts more anxious. Identifying the early signs of the fight or flight response can be beneficial for a number of reasons.

✦ By identifying the early signs of the fight or flight response, you can become more aware of your stress and anxiety levels. This can help you take steps to address your stress before it becomes more intense or unmanageable (it is much harder to soothe our nervous system when it’s at a 10 vs. when it’s at a 6 or 7 stress).

✦ It can help you take proactive steps to prevent a full-blown stress response: Once you’re aware of the early signs of stress, you can take proactive steps to prevent a full-blown stress response. This might include engaging in relaxation techniques, reaching out for social support, or finding healthy ways to cope with your stress.

By identifying the early signs of the fight or flight response, you can take control of your stress and find greater balance and well-being in your life. One of the most effective tools for noticing and mapping patterns is nervous system mapping. You can learn how to map your nervous system in my post on it here.

3. Acceptance

Accepting the sensations of the fight or flight response as normal can go a long way towards reducing them. Worrying about your fight-or-flight response while it is happening sends more signals to the brain that you are in danger, with the result of increasing or prolonging the response. This can be seen in the case of panic attacks, where people think their panic attack will harm them, and as a result, the attack continues. Perhaps counterintuitively, accepting the sensations of the fight-or-flight response as normal can go a long way towards reducing them (Levitt et al., 2004).

While psychological acceptance of distressing experiences have been shown to be helpful on a variety of levels, this is also particularly difficult for neurodivergent people. There are several reasons why acceptance of emotions may be more difficult for neurodivergent individuals:

✦ One reason is that neurodivergent individuals are more prone to struggle with alexithymia or the ability to identify and label their emotions accurately. This can make it difficult to understand and make sense of their emotions, leading to avoidance of them or difficulty accepting them.

✦ Many neurodivergent people have experienced societal or cultural stigma surrounding their emotions. For example, they may have been told that certain emotions are “bad” or “wrong” and should be suppressed. This can lead to a lack of validation and acceptance of their emotions, making it more difficult to accept and express them.

✦ Many neurodivergent individuals have experienced trauma or other negative experiences that have impacted their ability to process and regulate their emotions. This can lead to difficulty accepting and managing their emotions, especially in situations that may trigger memories of these experiences.

Overall, acceptance of emotions may be more difficult for neurodivergent individuals due to a combination of factors. Our difficulty with accepting emotions means we are more vulnerable to flipping into panic and spirals when experiencing uncomfortable feelings. Working with a neurodivergent-affirming and informed therapist can help you work through some of these additional vulnerabilities.

4. Exercise

Studies have shown that exercise can be effective in reducing anxiety (Salmon, 2001). While the exact mechanisms are still being studied, one theory is that the mild stress of exercise helps improve our resilience to stress in general. Other theories suggest that exercise can reduce sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity (Curtis & O’Keefe, 2002).

It’s important to note that for neurodivergent individuals, sticking to a regular exercise routine can be challenging due to executive functioning challenges, fatigue, and sensory and coordination issues. However, with planning and support, it’s possible to find activities that are enjoyable and manageable. Rather than focusing on traditional exercise, it can be helpful to find pleasurable forms of movement and pair them with enjoyable activities, such as walking while listening to a favorite book, podcast, or music. By prioritizing movement that feels good, you can reap the benefits of exercise while also enjoying the activity itself.

5. Practice Mindfulness

Mindfulness is the practice of being present and fully engaged in the moment. By focusing on the present and not worrying about the past or future, mindfulness can help to reduce stress and anxiety.

One way to practice mindfulness is by focusing on your breath or a mantra. You can also engage in mindfulness activities such as coloring or journaling. By directing your attention to the present moment and tuning out anxious thoughts that may be amplifying the fight-or-flight response, mindfulness can help you find a sense of calm and balance. Try to focus on the sensations in your body, the sounds around you, or any other sensory experience that can ground you in the present moment.

6. Rule Out Medical Conditions

It is important to rule out medical conditions that could be contributing to an overactive fight or flight response. While mental health issues are a common cause, other medical issues could also be at play. For example, heart arrhythmias can create a sense of panic or dysautonomia, and other nervous system-based dysregulations can contribute to underlying issues with the fight-or-flight response. Neurodivergent individuals may be more susceptible to Dysanatonia conditions such as POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome) which can make them more vulnerable to nervous system reactivity.

In addition, certain medications can activate the HPA axis and create a sense of panic. If you frequently experience panic symptoms or fight-or-flight activation, it is crucial to rule out any medical or body-based causes. Make sure to consult with a healthcare professional to address any underlying medical issues that may be contributing to your overactive fight or flight response.

Summary: How to Calm Fight or Flight Response

In today’s fast-paced world, our bodies are often subject to various stressors that activate our fight or flight response. While this response is beneficial in short bursts, chronic activation can lead to a range of physical and mental health problems. The good news is that there are ways to manage this response and prevent it from negatively impacting our lives. By understanding and managing our fight or flight response through mindfulness, exercise, and identifying triggers, we can prevent it from negatively impacting our mental and physical health. It’s also important to rule out any medical conditions that may be contributing to an overactive response. With the right tools and support, we can find balance and live a more peaceful and fulfilling life.

References

✦ Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2019, August 12). Fight-or-flight response. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/fight-or-flight-response