Some links in this post may be affiliate links, which means I earn a small commission if you make a purchase through those links at no additional cost to you

I know a thing or two about demand avoidance! My inclination to sidestep demands manifests in many subtle ways. For instance, I dislike making plans with others—whether it’s scheduling a coffee outing, a walk, or even a brief phone call. I much prefer spontaneous socializing. Once I commit to meeting someone, what was once a simple arrangement transforms into a demand, burdening me with a sense of obligation (even if it is someone I enjoy and genuinely want to see!). My demand avoidance contributes to my hesitancy to embrace new commitments. The thrill of starting a novel project can quickly morph into a demand, dampening the initial excitement.

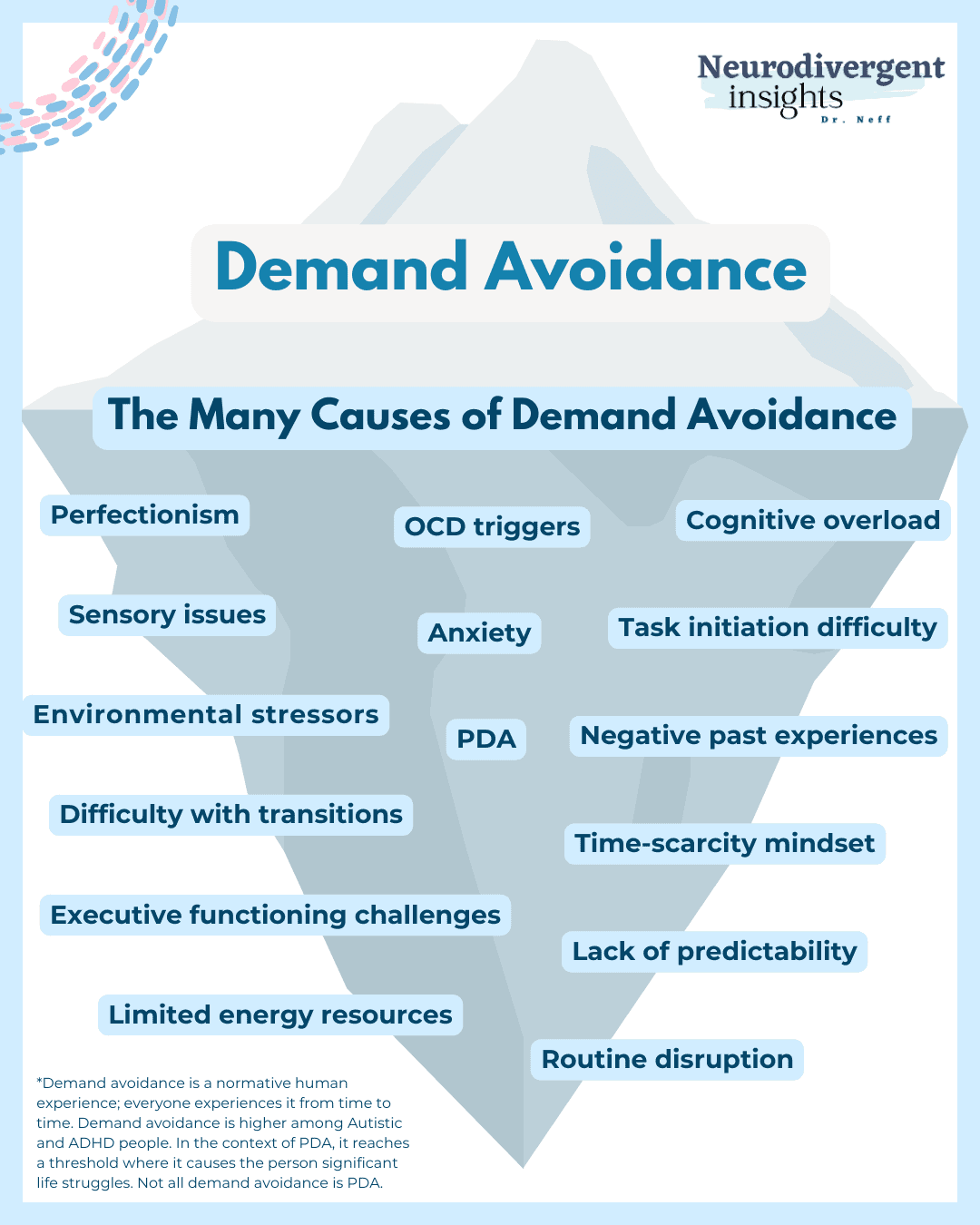

Demand avoidance is a sneaky thing that can wreak havoc in our lives. This holds especially true for people with Pathological Demand Avoidance* (PDA), wherein demand avoidance escalates to a level that many would label as “pathological” (although the term isn’t my preference; more on language in a minute). In such cases, demand avoidance leads to significant distress, casting a shadow over daily life — making the simplest of tasks difficult to accomplish. While demand avoidance is most closely associated with PDA, this blog post aims to transcend the boundaries of PDA and delve into demand avoidance on a broader scale. More precisely, it explores the nuanced distinction between normative or neurodivergent demand avoidance and PDA-related demand avoidance.

I have observed an emerging trend on social media and other platforms — the conflation of demand avoidance with PDA. It’s becoming increasingly common to assume that if an individual, be it an adult or a child, exhibits demand avoidance, they inherently fall under the PDA umbrella. While this assumption might hold true in some instances, it’s important to recognize that demand avoidance can arise due to a range of factors beyond PDA. So, while it’s wise to consider PDA when encountering persistent struggles with commonplace demands, exercising caution in labeling every instance of demand avoidance as PDA is equally essential.

In today’s article, I will untangle these two distinct experiences. Drawing from both research, clinical work, and my own lived experience as a parent of a PDAer and an Autistic-ADHDer with pronounced demand avoidance (though not identifying as PDA). Here’s what we’ll cover today:

✦ An overview of PDA

✦ Demand avoidance defined

✦ The demand avoidance iceberg (factors contributing to demand avoidance)

✦ The difference between PDA and demand avoidance

✦ Follow up resources and where you can learn more about PDA

So, let’s dive in!

Understanding PDA

PDA, or Pathological Demand Avoidance (or the preferred term Pervasive Drive for Autonomy), is a term primarily recognized within the United Kingdom and has not yet received formal classification in the United States. The term was coined by Elizabeth Newson, a British developmental psychologist, in the 1980s to describe the profile of a group of children she had seen for assessment.

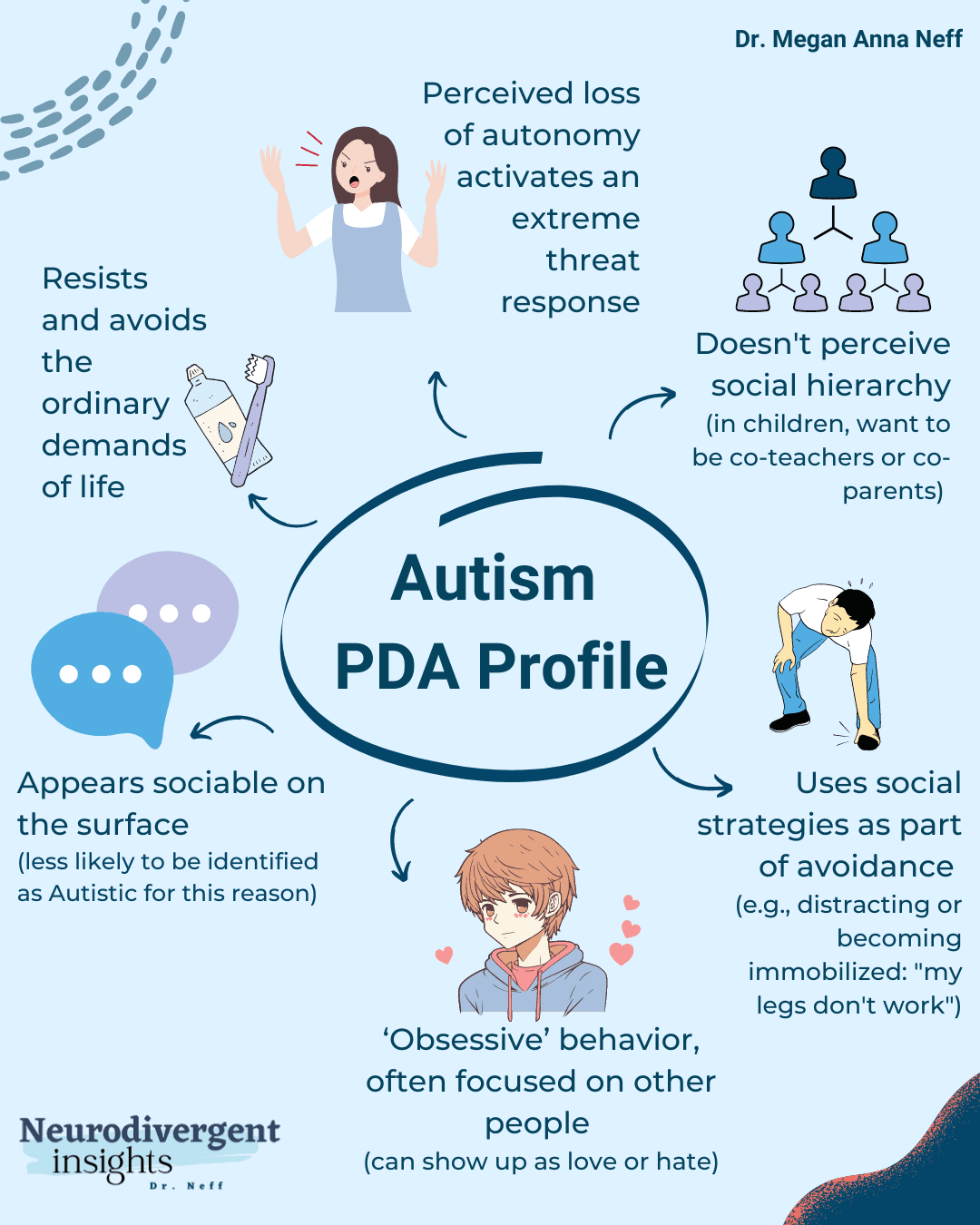

This concept falls under the autism spectrum and is a subtype of autism. It is characterized by a constellation of attributes marked by a strong inclination to resist and evade demands, even when the individual may actually wish to do them. At its core, the primary drive behind demand avoidance in PDA is the protection of an individual’s autonomy. There are seven fundamental characteristics often associated with PDA:

Exploring the Core Traits of PDA

The core traits of PDA include:

1. Evading Everyday Demands: This encompasses a significant aspect of PDA—individuals with PDA tend to resist and steer clear of even routine or seemingly insignificant demands (such as brushing teeth, taking a shower, putting shoes on, and doing work in class).

2. Autonomy Protection: The intense desire for autonomy and the simultaneous avoidance of external control are pivotal in PDA. This profound urge for independence can trigger heightened anxiety, sometimes to the point of panic attacks or meltdowns, when this autonomy is threatened.

3. Utilizing Social Strategies: A noteworthy facet of PDA is the strategic use of social tactics as a means of avoiding demands. This includes employing various techniques such as distraction, making excuses, outright refusal, or even engaging in role-playing to circumvent demands. This is often misinterpreted as manipulative for the people around the PDAer.

4. Concealed Social Communication Struggles: Despite challenges in allistic social interaction and comprehension, people with PDA often have a strong use of language which enables them to blend in more. They often exhibit relatively strong surface-level social communication skills. When they have a sense of autonomy and control, they are often described as charming and witty. This can mask underlying difficulties in understanding and processing non-autistic communication cues.

5. Intense ‘Obsessive’ Behaviors: A common feature of PDA is the manifestation of ‘obsessive’ behaviors, which can be directed toward others or even focused on performance-related demands. These behaviors often stem from acute anxiety.

6. Flourishing in Role Play: Individuals with PDA tend to thrive in role-playing and pretend scenarios. Their comfort in these imaginative contexts can sometimes be taken to an extreme, shaping their interactions and relationships.

7. Social Hierarchy: Difficulty perceiving social hierarchy (this is an Autistic trait), paired with a value of equality (also an Autistic trait), paired with a high need for autonomy, means that issues around social hierarchy can be particularly pronounced. For example, a child may wish to be a “co-teacher” or “co-parent” to the adults in their life.

The intricate nature of these traits can lead to confusion among parents and healthcare professionals, often resulting in misdiagnoses. It’s crucial to acknowledge that while demand avoidance stands as a hallmark of PDA, there is a constellation of traits that contribute to the overall profile. The profile is much bigger than demand avoidance. PDA should not be identified or diagnosed based on demand avoidance alone.

What is Demand Avoidance?

Now that we have briefly explored PDA let’s take a closer look at what normative Demand Avoidance is. Demand avoidance is characterized by a strong aversion to perceived demands. There are many reasons a person may experience demand avoidance, PDA just being one of those reasons. In fact, every human, at some point in their life, will experience demand avoidance. It is a normative human experience that occurs on a spectrum.

Neurodivergent Demand Avoidance

Demand avoidance in autism and ADHD is quite common. The majority of Autistic and ADHD people have a high degree of demand avoidance for reasons other than PDA. From executive functioning struggles to sensory issues to the stress of navigating a neurotypical world, there are hundreds of reasons that neurodivergent demand avoidance is a common experience. I’m going to walk you through some of the factors that contribute to my own personal demand avoidance as an Autistic ADHDer.

Demand Avoidance From the Inside

I have a long history of demand avoidance and of figuring out hacks to work around my demand avoidance! For me, demand avoidance is connected to the following factors:

A Scarcity of Time Mindset

I am frugal with my time. Perhaps due to my existential nature or the fact that I have limited energy or the fact that I am impatient and HATE wasting time, I am fiercely protective of my time. I live with the experience of never having enough of it. Unless I see the value in the task, demands that demand my time cause a great deal of internal agitation and irritability.

Unpredictable Energy

Due to chronic fatigue and chronic pain (experiences common among neurodivergent people), I never know what sort of energy I will wake up with. This makes me cautious about committing to future activities and fuels my time-scarcity mindset.

Unpredictable Interest

Unpredictable Interest

Due to ADHD’s interest-based nervous system, I never know where the dopamine will lead me. I have learned I am much more efficient when I follow the dopamine, and I’ve created my life in such a way that I can mostly do that. When I schedule things ahead, I don’t know that the interest (thus the dopamine) will be there.

Perfectionism, Comprehensiveness, and Bottom-Up Processing

The consistent feedback I’ve received from supervisors/employers is that my work is thorough (sometimes too much so). I don’t know how to do simple–I do complex. My work and projects always grow (for example, every month when I make a workbook for my membership area, I tell myself—”This month it will be a 30-page workbook,”—and each month, the content grows and grows and becomes a 100-page workbook!). According to search engines, an ideal blog post is about 1,000 words; most of mine are regularly 3,000-4,000 because I struggle to simplify the thing!

I like to be thorough; I like to be comprehensive and nuanced. It feels like I am lying if I offer the surface-level answer to a thing. And once my brain sees connections or information, I can’t NOT SAY it (again, it feels like I’m lying or being less than honest to say less). This means that projects I commit to take more time. If someone asks me to speak, write an article, or do a podcast, I will inevitably put in many more hours of preparation than the average person. In short, demands that may be simple for others are complex for me. I make them complex because my brain doesn’t know how to do simple.

People Pleasing

This one is a bit of a paradox. It isn’t very people-pleasing of me to say no to requests. But it is my intense people-pleasing that makes demands so hard for me. When I do commit to something, I want to do it well and fear disappointing others. This then triggers my perfectionism and rejection sensitivity dysphoria.

Sensory Sensitivities

The majority of social events are too overwhelming for me. In a group larger than 5 or 6, I often low-grade dissociate as a response to the sensory overload. I don’t like crowds, bright lights, noise, or small talk. All of these are experienced as sensory demands, which I work hard to avoid! We live in a society where many of the everyday demands involve high sensory exposure (going to the grocery store, picking kids up from school, going to a restaurant or coffee shop, a wedding or graduation, or more). Typically, I avoid these demands for sensory reasons.

Executive Functioning

While my executive functioning works decently when I’m genuinely interested in something, it doesn’t work so well on a day-to-day basis and works quite terribly when I am navigating complex and logistical tasks. Other times, I struggle to know how to start a task and break it down, especially if it is new. I also struggle with task initiation (common among people with executive functioning challenges). These all make responding to demands more difficult for me.

Task Initiation and Transition Struggles

This is connected to the above section. Task initiation tends to be more difficult for Autistic and ADHD people. This is sometimes referred to as “Autistic inertia” and is related to our brain wiring (which is both hyper and hypo-connected), making it harder to transition between tasks. Difficulty initiating new tasks or stopping a current task can lead to significant demand avoidance for me. This is why when I am deeply focused on a piece of writing and a child asks me for something I have a hard time switching my focus to respond to my child’s request.

A Desire for Autonomy

I value my autonomy A GREAT DEAL. I like helping people if it is my idea, but I don’t like feeling obligated to people. This is something I used to feel a great deal of shame about. I care deeply about humanity and helping others, and I simultaneously can feel the most intense irritability when my autonomy is being infringed upon. And yes, I realize this sounds like PDA. However, my drive for autonomy feels more aligned with the normative Autistic drive for autonomy vs. the PDA drive for autonomy (see the section on teasing apart PDA and demand avoidance for more thoughts on the difference).

Stress

As mentioned above, demand avoidance occurs on a spectrum, and it tends to spike during times of stress. This is certainly true for me and is connected to anxiety. When I’m stressed, my time-scarcity mindset kicks in even more, my fight-flight system is running right under the surface, and I struggle, and my need for a predictable routine is heightened. Incoming demands can trigger any of these sensitivities and make me more prone to have a negative reaction around an incoming request or demand, especially if it involves a schedule change or a time-involved task.

Anxiety and OCD

While thankfully, anxiety and OCD don’t play a big part in my life anymore, they historically have. Anxiety and avoidance go hand in hand (we avoid the things we’re anxious about, which inevitably strengthens the anxiety–it’s a vicious loop!). I used to avoid weekly demands like going to the grocery store, medical visits, or other demands because they were anxiety or OCD triggers.

Lack of Predictability

If the request or demand is not precise and clear and introduces an unpredictable schedule or event into my life, I am much more likely to pass. For example, I get a lot of requests from fellow professionals to “hop on a call.” I rarely, if ever, say yes to these sorts of requests a) because it’s social, but more so because what the person has proposed is highly unpredictable. I don’t know what they want to talk about, what the frame of the conversation is, how long it will be, and more. Routine Disruption

If the request or demand is not precise and clear and introduces an unpredictable schedule or event into my life, I am much more likely to pass. For example, I get a lot of requests from fellow professionals to “hop on a call.” I rarely, if ever, say yes to these sorts of requests a) because it’s social, but more so because what the person has proposed is highly unpredictable. I don’t know what they want to talk about, what the frame of the conversation is, how long it will be, and more. Routine Disruption

When I wake up, I have an idea of how the day will go. I am okay if the routine changes at my will, but I feel very differently if it changes for reasons outside of my control. Any incoming request or demand threatening to disrupt my routine causes irritation. The protection of my routine will often result in the avoidance of incoming requests and demands.

Other reasons for demand avoidance

There are many other reasons for demand avoidance. Negative past experiences can heighten our reluctance to participate in certain activities, while difficulties in regulating our emotions can hinder engagement with tasks invoking intense feelings. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) may lead to avoidance of routine places and activities due to triggers. Additionally, social and communication differences might cause us to evade tasks involving interacting with allistic and neurotypical people. Moreover, our surroundings also play a role; an overly chaotic or demanding environment can intensify demand avoidance.

Demand Avoidance in the Context of PDA

In the context of PDA, the person will struggle with demand avoidance for the above reasons AND struggle for a much more fundamental reason — demands invoke a perceived threat to one’s autonomy. In PDA, demand avoidance is conceptualized as an extreme nervous system response (the body goes into fight-or-flight in response to a demand and becomes immobilized).

PDA Demand Avoidance vs. Neurodivergent Demand Avoidance

Because someone with high-demand avoidance and someone with PDA may look similar on the outside, it can be tricky to tease apart the difference. Here are some considerations when working to tease apart normative or neurodivergent demand avoidance from PDA demand avoidance.

What is the Cause of the Avoidance?

In the context of PDA, the majority of demand avoidance will be associated with autonomy threats. The person may not have language for this, and it may be experienced as simply “because it is a demand.” In the context of normative demand avoidance, you can often identify a cause for the avoidance. It may be sensory reasons, executive functioning struggles, task initiation difficulty, or something else.

Consider the Nervous System

People with PDA have an “ice-thin” window of tolerance. This means their stress response is easily activated, and they chronically go into fight-flight or freeze-fawn mode. PDAers may not be able to articulate what it feels like to be within a regulated window of tolerance because their nervous systems are constantly activated. While Autistic people and ADHDers also have more sensitive nervous systems, this aspect will be more pronounced in a PDAer than a non-PDAer.

Consider Developmental History

While there is much we’re still learning about PDA, current thinking is that this is a genetic neurotype a person is born with. When I reflect back on my daughter’s early years, I recall how difficult nursing was. Nursing is not an autonomous activity! It involves a high level of coordination and dependence on another human being. Beginning at a young age, nursing began to feel like a battle for control. Not having the lens of PDA (or autism), I was deeply confused by why our nursing relationship did not echo the maternal stories I had heard (that nursing was a magical bonding experience). I also didn’t realize how different this experience was until I had my son three years later and experienced nursing with a non-PDAer. Beyond nursing, there are a hundred ways I can see demand avoidance from 9 months on with my PDA child. While PDA can be internalized, you would typically expect to see early signs of PDA in children.

Avoidance Tactics

One core feature of PDA is “avoidance tactics,” and the people around them often experience these as manipulative. However, we need to remember that this is coming from an extreme fight-flight response and is not intended to be manipulative; rather, it is derived from a drive for safety.

In the context of PDA, the strategies employed for avoiding tasks can often demand more energy than the tasks themselves. This aspect used to frustrate me as a parent before I fully comprehended the situation. Elaborate avoidance behaviors, like the long-winded arguments used to avoid fetching a glass of water or the intensifying meltdowns over demands, would drain the family’s time and energy considerably more than the actual task. This paradox seemed entirely illogical.

These tactics can also be intricate and veiled, sometimes even occurring unconsciously. For instance, a child might assert, “My legs won’t work, so I can’t do that.” It’s crucial to understand that while a parent could interpret this as a deliberate manipulation or lie, the child’s body might genuinely be responding with physical incapacity (an unconscious mechanism triggered to further aid demand avoidance or an extreme fight-flight-freeze reaction).

For someone with normative demand avoidance, there may still be avoidance tactics. However, they won’t be as disproportionate. For example, I will avoid writing a report by instead writing a blog post I am more interested in. Or I will clean my house rather than write a blog post. I may also try to find ways to get out of social events, but these are calculated decisions, and the avoidance strategy doesn’t cost me more energy than simply doing the thing. While demand avoidance causes stress in my life, the avoidance tactics do not. In the context of PDA, the avoidance tactics themselves can become a source of stress.

Drive For Autonomy

While PDA technically stands for “Pathological Demand Avoidance,” I prefer the term “pervasive drive for autonomy,” coined by Tomlin Wilding. At the heart of demand avoidance for a PDAer is autonomy. You will see this drive for autonomy show up in a multitude of ways. For example, when I watch television with my daughter, she holds the remote. This is partly because she has more sensitive auditory processing but also because of the need for autonomy, and this gives her control over when the show is stopped, paused, or the volume.

Before I had a PDA lens, this used to be an area where we would try to encourage her to be more flexible. I now understand that for her to feel safe enough to watch television with me or the family, she needs control of the television, and this is a reasonable accommodation for her PDA. There are a hundred other ways we have adapted to cultivate autonomy. Families with PDAers will also likely experience these “thousand little things.” Moments in the day that may seem like “no big deal” hold a lot of significance when you can see them through an autonomy lens.

While Autistic people do tend to be more protective of our autonomy than non-Autistic people, the intensity will not be the same. For example, I am perfectly comfortable watching TV with my daughter and letting her have the remote. However, when I am dependent on someone to a point where my routine and schedule are dependent on them or to where they are intruding with a request or asking a demand of me that is not self-initiated I have a strong Autistic response (this taps into my need for routine, predictability and a dislike of people placing expectations on me). So, while I have a stronger drive for autonomy than the average person, I have a greater tolerance for loss of autonomy than a PDAer, which does not cause as much difficulty in my life.

Intensity of Demand Avoidance

Traditionally, PDA was distinguished from autistic demand avoidance based on the severity or “pathology.” The name “Pathological Demand Avoidance” arose because the threshold of demand avoidance reached what was considered pathological levels. If you know my work or have been around Neurodivergent Insights for a while, you know I don’t love terms like “pathology.” So, let’s recontextualize this concept. With PDA, demand avoidance causes the person suffering and distress. For example:

✦ They want to brush their teeth, but they can’t because it’s a demand.

✦ They may want to get up and get a glass of water to quench their thirst, but they can’t because it’s a demand.

✦ They may want to go to martial arts class, but they can’t because it’s a demand.

✦ They may want to do the OT or PT exercises that they know will make them feel better, but they can’t because it’s a demand

To consider PDA, the level of distress around the person’s demand avoidance needs to be significant to where it impacts their day-to-day life.

Where Can I Learn More About PDA?

There are some fantastic PDA resources emerging. Whether you suspect you are parenting a PDAer, are PDA yourself, or are a therapist working with PDA families, here are some resources that can provide deeper learning and support:

✦ Check out the Master Class Dr. Donna Henderson and I did on PDA to understand the PDA profile better!

✦ Amanda Diekman (Author of Low Demand Parenting and PDAer) is hosting a 2024 Low Demand Parenting summit with a great lineup of speakers! It’s free if you attend live, or you can purchase an All Access Pass to watch at a leisurely pace.

✦ Check out our recent Divergent Conversations on the topic of PDA and demand avoidance.

✦ Dr. Donna Henderson has a great article on what PDA is Not What You Think it is!

✦ The Declarative Language Handbook is a great resource for learning more about declarative language use.

✦ The PDA Society has an informative article about approaches with PDA

✦ PDA: A Guide for Parents and Carers (a fantastic resource for parents and adults who work with children with PDA).

✦ A must-have Book on Low-Demand Parenting by Amanda Diekman (you can also check out my blog post on low-demand parenting here)

✦ The Low-Demand Parenting Summit provides loads of parenting advice and information for parenting children through a low-demand lens.

✦ Can I tell you about Pathological Demand Avoidance syndrome? (Told from the perspective of an 11-year-old. Good for pre-teens and teens)

✦ Kristy Forbes, an adult PDAer and parent, has fantastic resources and courses for parents.

✦ The Family Experience of PDA

✦ Pretty Darn Awesome: Divergent not Deficient: Understanding Pathological Demand Avoidance on the Autism Spectrum (told from the perspective of a child)

✦ For those on social media, AuDHD_Therapist is an Autistic-ADHD, PDA therapist who regularly shares their lived experience with PDA.

PDA Master Class

If you’re looking for a deep dive, Dr. Donna Henderson and I have partnered to create a fantastic MasterClass. As a parent, I found Dr. Henderson’s training to be incredibly helpful in understanding the core features of PDA and how to support my child effectively.

Dr. Henderson, author of Is This Autism?, is widely recognized as one of the leading assessors in the United States for Autistic girls and individuals with PDA. So if you want to understand PDA from a clinician’s point of view, this is a great resource! You can use the coupon code PDA10 to get $10.00 off the Master Class.

Conclusion

To summarize, PDA (commonly called pathological demand avoidance or pervasive drive for autonomy) is a profile of autism characterized by a need for autonomy. When autonomy is threatened, this invokes a fight-flight-freeze response. While extreme demand avoidance is a core PDA trait, PDA encompasses much more than demand avoidance.

Demand avoidance is a normative human experience and occurs on a spectrum. Neurodivergent demand avoidance refers to the fact that demand avoidance occurs more frequently in people with autism and ADHD. A person may experience demand avoidance for many reasons, including sensory issues, executive functioning challenges, task initiation struggles, and more. It is important that demand avoidance not be automatically equated with PDA. To tease apart the difference, it is important to consider things such as the reason behind the avoidance, the presence or absence of other PDA traits, the developmental history, the relationship to autonomy, and the person’s nervous system experience.

To learn more about PDA, consider checking out the Master Class with Dr. Hendreson, the Divergent Conversations podcast on the topic, or The PDA Society. I also encourage you to listen to lived experience voices such as AuDHD_Therapist (an Autistic-ADHD PDA therapist who openly speaks about their experience of PDA), Kristy Forbes (she is an adult PDAer who is also parenting PDA children and has several parenting strategies), or check out Amanda Diekman’s book.

* At times throughout this article I refer to PDA as Pathological Demand Avoidance, I use the term in this article for educational purposes and for clarity because it is the most widely known term. At other times throughout this article I use the term coined by Wilder “Pervasive Drive for Autonomy,” This is also the preferred term by many within the Autistic community and among PDAers. It is a more neurodivergent-affirming way of conceptualizing PDA.