Rethinking Autistic Communication

What if everything we thought we knew about Autistic communication was wrong? Traditionally, Autistic communication has been labeled a social deficit, and communication breakdowns attributed to shortcomings within the Autistic individual. However, emerging perspectives challenge this notion, recognizing autism as a difference rather than a deficit. Autistic people have their own distinct culture and ways of communicating, which are often misunderstood by non-Autistic individuals, and vice versa. This mutual misunderstanding is encapsulated in Dr. Damian Milton’s concept of the “double empathy problem,” where both Autistic and non-Autistic people struggle to understand each other’s perspectives.

These encounters, which I refer to as cross-neurotype interactions, occur when people of different neurologies come together. Research has shown that communication breakdowns happen more frequently in mixed neurotype groups than in groups composed solely of Autistic or non-Autistic individuals. This supports the idea that Autistic communication struggles are not rooted in a lack of social skills but in differing communication styles. Autistic people don’t lack social skills; they simply have specific, different ones. Understanding and embracing these differences is key to fostering better communication and connection across neurotypes.

This is why I often liken cross-neurotype interactions to cross-cultural interactions. Just as different cultures have their own norms and practices, different neurotypes have their own communication styles and social expectations. For example, when I lived in Malawi, I learned that it is considered rude to shake hands with the left hand, as the left hand is traditionally used for tasks considered unclean. Offering my left hand in a handshake would be seen as deeply disrespectful. There are countless norms like this to navigate when interacting across different cultures, and it’s not about one culture being right and another wrong—it’s about understanding that each culture operates within its own context, with its own reference points and meanings.

The same principle applies when we communicate across neurotypes. What may be considered polite, clear, or appropriate communication in one neurotype might be interpreted very differently in another. And of course, many of us navigate both neurological and cultural differences simultaneously, further complicating our interactions! Recognizing these differences and approaching them with curiosity can allow for more meaningful and empathetic connections.

If you’re like me, however, you might be thinking, “Sure, this sounds nice in theory, but is there proof?” I’m so glad you asked. In fact, Dr. Catherine Crompton, based in the UK, and her research team have explored this topic deeply, conducting several studies that shine a light on how communication dynamics unfold between Autistic and non-Autistic individuals. In the next section, we’ll review some of these key studies and what they reveal about the complexities and nuances of cross-neurotype communication.

Studies on Cross-Neurotype Interactions

Dr. Catherine Crompton and her research team have explored cross-neurotype interactions, effectively testing Dr. Milton’s double empathy theory. Their findings have been quite revealing, shedding light on how communication unfolds—or breaks down—when Autistic and non-Autistic individuals interact.

The Telephone Study Game

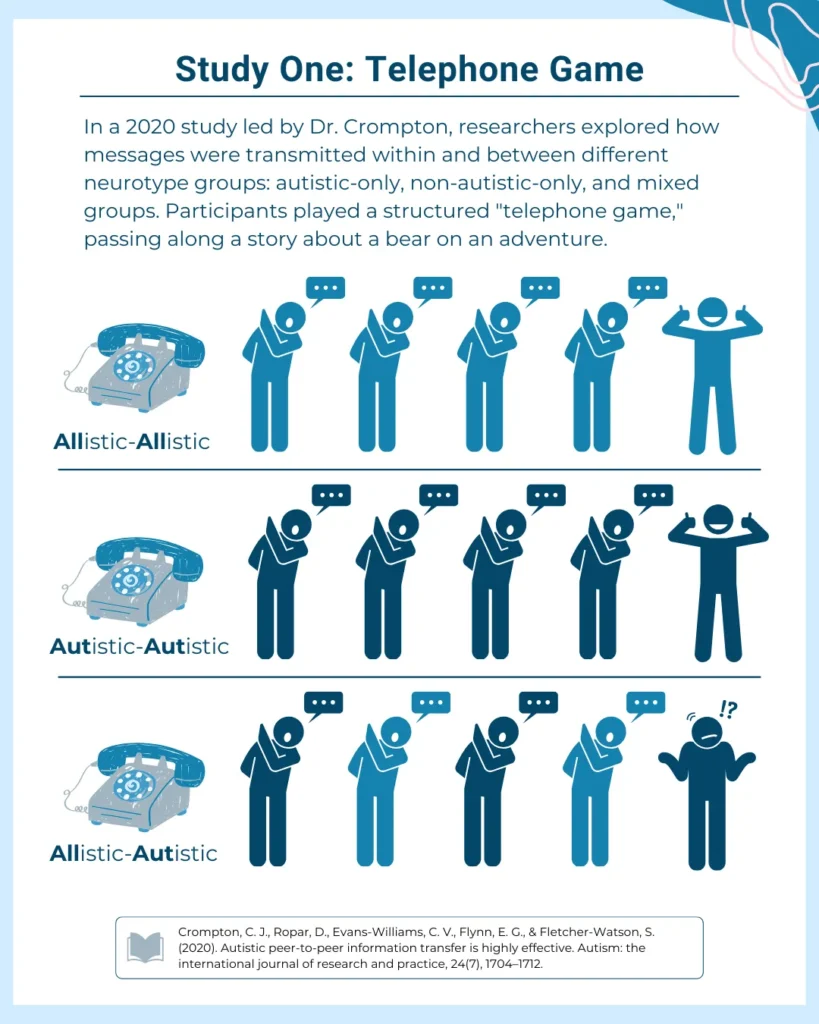

In one particularly insightful study led by Dr. Crompton and her colleagues (2020), the researchers explored how effectively messages were transmitted within and between various neurotypes. Participants were divided into three groups: those composed solely of Autistic individuals, solely of non-Autistic individuals, and mixed groups of both Autistic and non-Autistic individuals.

The test was an information chain task, reminiscent of the “telephone game” many of us played as children, but in a more structured and controlled environment. Each participant in the chain received a story and then passed it to the next person, with the final participant recounting the story aloud. In the mixed neurotype groups, participants alternated between Autistic and non-Autistic individuals in the chain, ensuring that each interaction was cross-neurotype.

The story used in these chains was about a bear on a surreal adventure—designed to be unpredictable and lacking in inherently social aspects, requiring participants to pay close attention and accurately transmit the details to maintain the story’s coherence.

As the story moved down the chain, the researchers observed and recorded where the message began to break down and how accurately it was transmitted to the final participant.

The results were telling: In groups of only one neurotype–either only Autistic individuals or only non-Autistic individuals–the story tended to remain relatively intact for a longer period. However, in the mixed neurotype groups, the story fell apart much more quickly, becoming significantly altered or even unintelligible by the time it reached the final participant. This rapid breakdown in mixed groups highlighted the unique challenges in cross-neurotype communication.

If communication challenges were solely or even primarily due to deficits within Autistic individuals, one would expect the worst performance to be in the autism-only group.. That wasn’t the case; communication breakdowns occurred sooner and more frequently in mixed-neurotype groups compared to same-neurotype groups. Misunderstandings occurred not because Autistic people can’t communicate effectively, but because their communication styles differ from those of non-Autistics. In similar-neurotype groups, shared styles kept the story intact, while mixed groups faced quicker and more substantial communication breakdowns.

Neurotype Matching Study

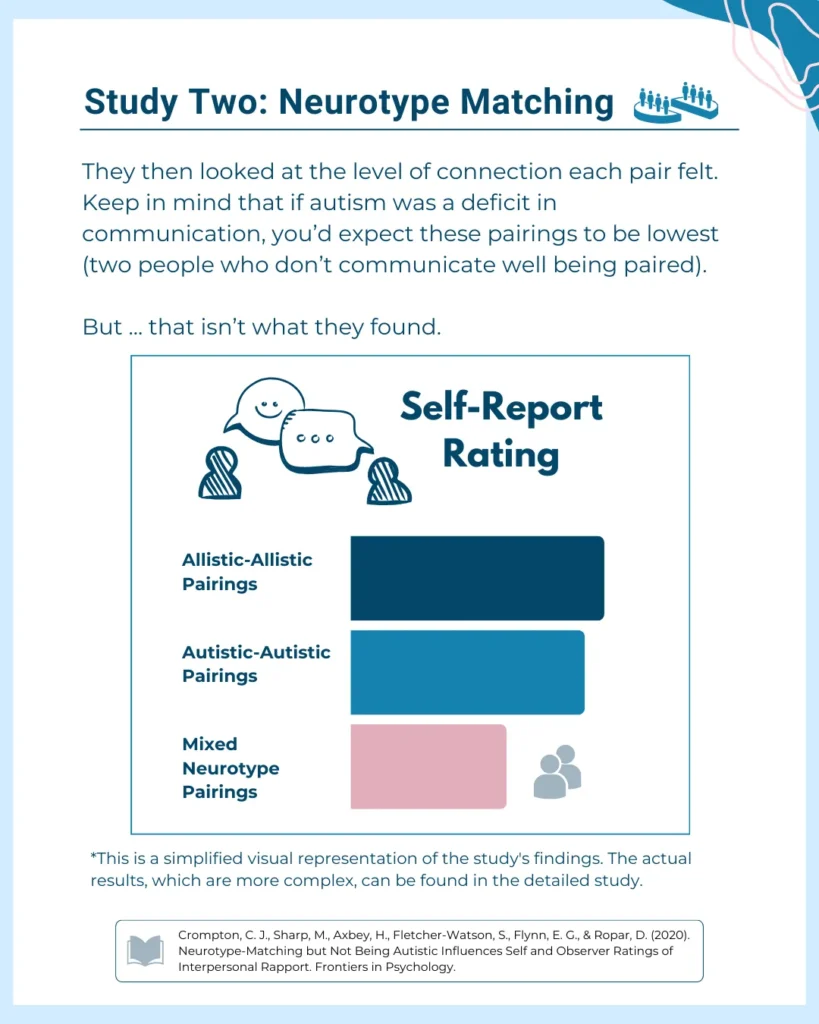

In another study, also led by Dr. Crompton in 2020, individuals were paired into groups of two to perform various tasks. The 12-group study included Autistic pairings, allistic (non-Autistic) pairings, and mixed-neurotype groups. Participants in each group completed three semi-structured tasks with their partners and then rated their rapport—how well they felt they connected—after each activity.

The results, based on the participants’ self-reported experiences, were quite revealing:

Non-Autistic pairings reported the highest level of rapport.

Autistic pairings reported the second-highest level of rapport.

Mixed neurotype pairings had the lowest level of rapport.

The researchers also required that 80 observers watch recordings of the interactions and rate their level of connection. The observers didn’t know the neurological makeup of the pairings; they simply watched the interactions. Surprisingly, the observers rated Autistic pairings as having the highest rapport, followed by allistic pairings, with mixed neurotype pairings again rated lowest.

If autism were truly a social-communication deficit, we would expect the worst performance from Autistic pairings, since it would be two “socially inept” people interacting. However, the study found the opposite; neurological matching mattered more than whether or not a person was Autistic.

Reframing Autistic Communication and Its Implications

One of the key challenges in cross-neurotype interactions is that neurodivergence is often invisible, making communication misunderstandings harder to recognize. People often aren’t even aware they’re engaged in a cross-neurotype exchange, which can lead both to content and meaning misinterpretations. These differences are then misattributed to character flaws rather than differences in communication styles.

For example, Autistic people tend to communicate directly and literally and may not experience hierarchy and authority in the same way non-Autistic (allistic) individuals do. This difference can easily lead to misunderstandings. Imagine an Autistic employee giving straightforward feedback to a manager, who sees this directness as rudeness or a challenge to their authority. In reality, while it may or may not be a challenge to their authority, it’s actually a communication disconnect between two neurotypes.

These findings challenge the long-held belief that Autistic people inherently lack social skills. Instead, they reveal that Autistic communication is not deficient but different, requiring mutual adaptation and understanding. This perspective shift is similar to how we approach cross-cultural interactions, where differing communication styles are acknowledged and respected.

Recognizing these differences as legitimate and valuable ways of connecting highlights that the responsibility for adaptation should not fall solely on Autistic individuals. There is a pressing need for greater awareness and understanding of diverse communication styles across neurologies and this emerging paradigm encourages more inclusive and empathetic relationships.

Implications:

Here are some of the implications and takeaways from these findings:

Treat Cross-Neurotype Interactions Like Cross-Cultural Ones: Rather than seeing communication differences as deficits, we should approach cross-neurotype interactions with the same respect and curiosity we bring to cross-cultural exchanges.

Reframe Social Skills Training for Autistic Individuals: When we teach Autistic children ‘social skills,’ it’s important to be clear that they’re learning allistic (non-Autistic) social skills. These can be helpful in certain situations, but they’re just one way to communicate—not the ‘right’ way or the only way.

Embrace Autistic Communication Styles: By embracing our natural ways of communicating, we create space for genuine, meaningful connections. It’s about recognizing that our communication is valid and valuable just as it is.

4. Challenge the Deficit Narrative: The idea that Autistic people lack social skills is outdated. These findings show that Autistic communication isn’t deficient; it’s different. What we need is mutual understanding and adaptation, not correction.

5. Increase Awareness and Encourage Adaptation: We all benefit from a deeper awareness of how communication styles differ across neurotypes. This understanding can lead to more inclusive and empathetic interactions, helping to reduce misunderstandings when different neurotypes come together.

Summary

The double-empathy problem and recent empirical studies on cross-neurotype interactions challenge the long-held belief that Autistic people inherently lack social skills. Instead, the findings suggest that Autistic social skills are not deficient but different.

A significant paradigm shift is underway as we begin to recognize that Autistic communication is not a deficit but a difference that requires mutual adaptation and understanding. Without this mutual understanding, differing communication styles can lead to confusion and misunderstandings. Rather than placing the onus solely on Autistic individuals to undergo “social skills training,” this new perspective emphasizes the importance of increasing awareness and understanding of diverse communication styles across neurotypes.

By embracing this approach, we can better bridge the communication gaps that often arise in mixed-neurotype interactions. This shift will not only foster more inclusive and empathetic relationships but also pave the way for a more nuanced understanding of neurodivergent communication as a legitimate and valuable way of connecting with others.

Crompton, C. J., Ropar, D., Evans-Williams, C. V., Flynn, E. G., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2020). Autistic peer-to-peer information transfer is highly effective. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 24(7), 1704–1712.

Crompton, C. J., Sharp, M., Axbey, H., Fletcher-Watson, S., Flynn, E. G., & Ropar, D. (2020). Neurotype-Matching but Not Being Autistic Influences Self and Observer Ratings of Interpersonal Rapport. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 586171.

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the ‘double empathy problem.’ Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887.