Paragraph Lorem Ipsum

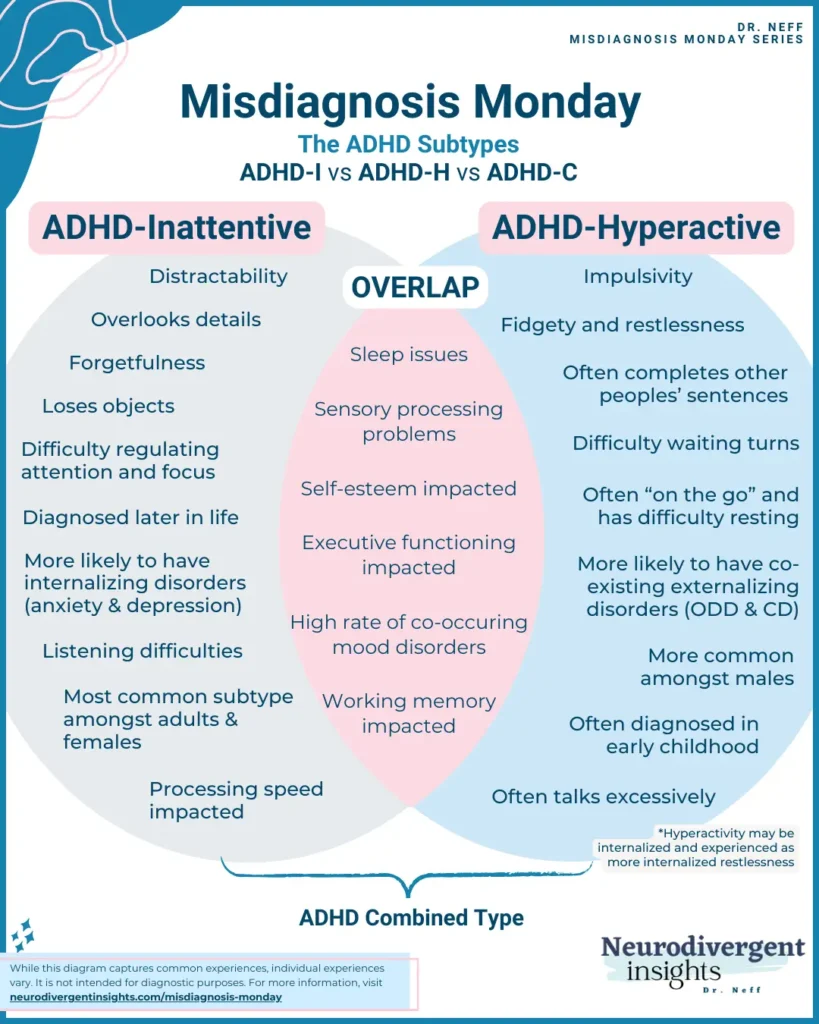

Did you know there are different forms of ADHD? In fact, there are three distinct types. When it comes to children, ADHD Hyperactive Type (ADHD-H) is the most recognized. In adults, ADHD Inattentive Type (ADHD-I) is more common. But what sets these types apart?

As a neurodivergent clinician specializing in working with neurodivergent adults, and someone diagnosed late in life with both ADHD and Autism, I understand the abundance of misinformation about various neurotypes. In this article, I will explore the different types of ADHD and how to distinguish between them. I’ve also included information on the diagnostic criteria for ADHD to help demystify the process of diagnosis.

Contents:

Overview of the ADHD Subtypes

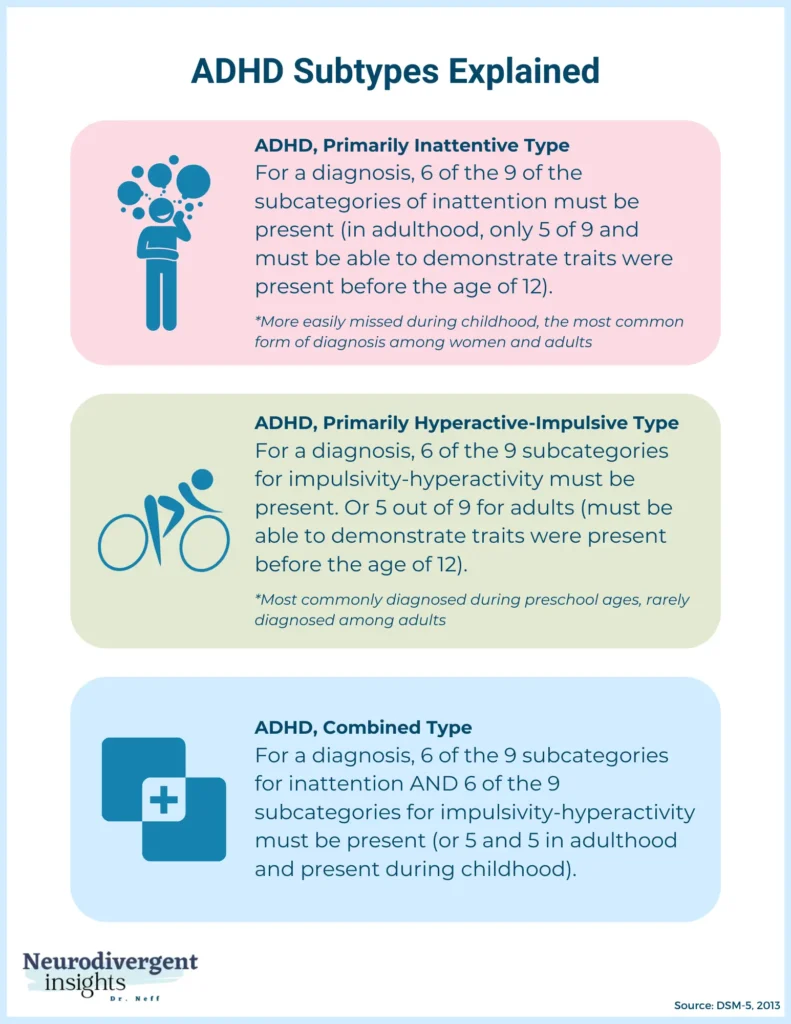

Before getting into the similarities and differences between the different ADHD types, let’s define them. There are three types: ADHD Inattentive type (ADHD-I), ADHD Hyperactive and Impulsive type (ADHD-H), and ADHD Combined type (ADHD-C).

ADHD-I is characterized by difficulties regulating attention

ADHD-H is characterized by impulsive and hyperactive behavior

ADHD-C is characterized by both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity

Let’s get into it.

ADHD Inattentive Type (ADHD-I)

ADHD-inattentive type (formally known as ADD) is marked by:

Difficulty regulating attention

A tendency to make careless mistakes

Overlooking details, distractibility

Difficulty organizing and finishing tasks

Forgetfulness

Difficulty listening

Difficulty sequencing events or following detailed instructions

Difficulty with routine chores.

Working memory and processing speed are often impacted in the context of ADHD-inattentive type (processing speed may not become impacted until too many tasks are placed on the person). This type is the most common type diagnosed among adults and females.

Inattentive ADHD does not look like the stereotypical presentation of ADHD. Most people think of a young child who is struggling to sit in their seat or running around tirelessly. However, ADHD-I can look like:

daydreaming quietly in class

feeling anxious or sad

difficulty listening (which may be attributed to being “spacey.”

shyness

people-pleasing

trouble maintaining friendships

picking at cuticles or skin

being a perfectionist

People with ADHD-I are more likely to have Sluggish Cognitive Tempo (SCT). SCT was described by Russel Barklay, and is characterized by dreaminess, mental fogginess, slow working memory, hypoactivity (less activity), staring frequently, inconsistent alertness, and excessive daydreaming. It is estimated that 30-63% of people with inattentive type ADHD also have SCT (Fassbender et al., 2015)

Inattentive ADHD may be the most difficult to diagnose as it is often dismissed as the person being “spacey”, or “apathetic”, or experiences are attributed to anxiety or a mood disorder. Even when diagnosed, they are less likely to receive medication for their ADHD. Willcutt, 2012 found that while ADHD-I was the most common subtype, people with ADHD-C were more likely to be referred for clinical services. This finding suggests that those with ADHD-I may need to take extra initiative and engage in self-advocacy to ensure they obtain the appropriate support and services.

ADHD Hyperactive and Impulsive Type (ADHD-H)

ADHD-Hyperactivity is the most common form of ADHD diagnosed in preschoolers. It is associated with behavioral difficulties in early childhood and co-occurs with Oppositional Defiance Disorder (ODD) and Conduct Disorder (CD) at high rates (Bendiksen et al., 2014). ADHD-H is characterized by the need for constant movement. Such folks often fidget, squirm, and get up from their seat to walk around or stand. Children with ADHD-H are often described as if they are “driven by a motor” (running around excessively). Hyperactivity may also show up as excessive talking, difficulty waiting their turn, and difficulty with self-control may lead to impulsive behaviors (blurting out answers, engaging in risky activities, and so forth). This type of ADHD is the most recognizable and thus diagnosed more readily than ADHD-I. It is more commonly diagnosed among children and men.

ADHD Combined Type (ADHD-C)

ADHD-C has a high prevalence rate and is the most common presentation among children.

Combined type ADHD is diagnosed when a person presents with six out of the nine symptoms of both inattention and hyperactivity. ADHD-C also co-occurs with externalizing disorders such as ODD and CD at high rates (Bendiksen et al., 2014). People with ADHD-C often have co-occurring internalizing disorders (anxiety and depression).

ADHD Screener: While we’re on the topic of the DSM and diagnosis, the ASRS is the most widely used screener for ADHD, and this instrument aligns closely with the DSM criteria.

DSM-5 Criteria for the ADHD Subtypes

ADHD-I

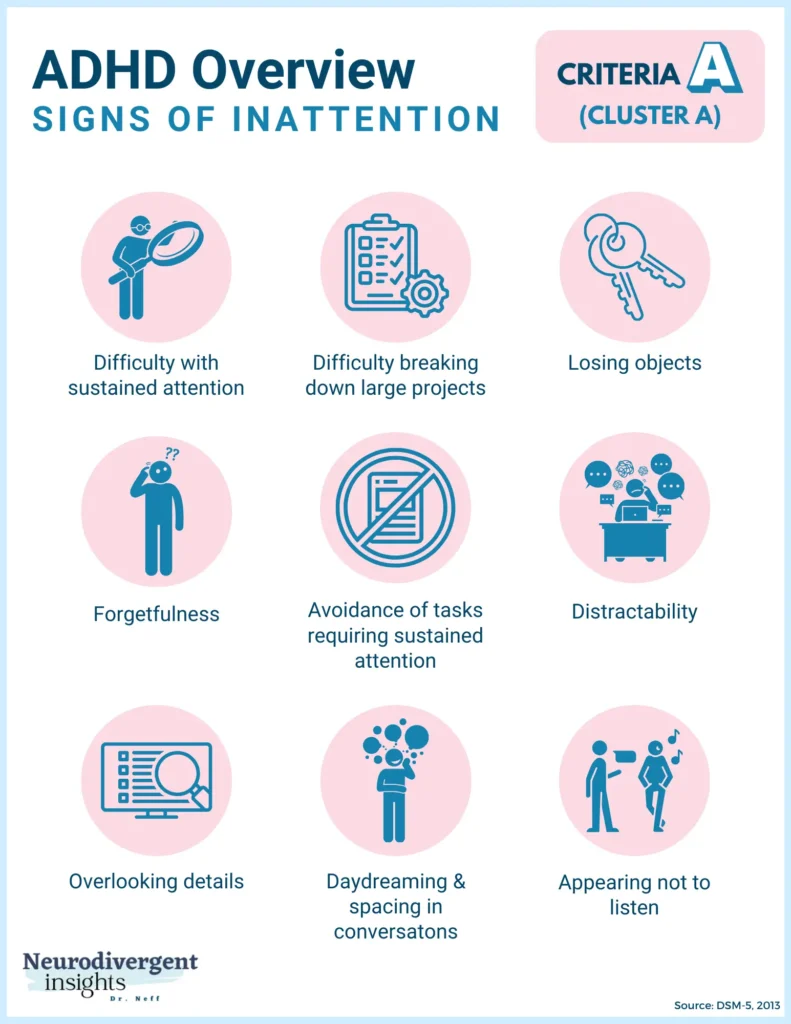

Here is how ADHD-I is diagnosed based on the DSM-5 criteria. Six of the following nine symptoms of inattention must be present for the last six months:

Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or during other activities (e.g., overlooks or misses details, work is inaccurate).

Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (e.g., has difficulty remaining focused during lectures, conversations, or lengthy reading).

Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly (e.g., the mind seems elsewhere, even in the absence of any obvious distraction).

Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.g., starts tasks but quickly loses focus and is easily sidetracked).

Often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities (e.g., difficulty managing sequential tasks; difficulty keeping materials and belongings in order; messy, disorganized work; has poor time management; fails to meet deadlines).

Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (e.g., schoolwork or homework; for older adolescents and adults, preparing reports, completing forms, reviewing lengthy papers).

Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).

Is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli (for older adolescents and adults, may include unrelated thoughts).

Is often forgetful in daily activities (e.g., doing chores, running errands; for older adolescents and adults, returning calls, paying bills, keeping appointments)

ADHD-H

To meet the criteria of ADHD-H, six of the following nine symptoms of hyperactivity must be present for the last six months:

1. Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet or squirms in seat.

2. Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected (e.g., leaves his or her place in the classroom, in the office or other workplace, or in other situations that require remaining in place).

3. Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is inappropriate. (Note: In adolescents or adults, may be limited to feeling restless.)

4. Often unable to play or engage in leisure activities quietly.

5. Is often “on the go,” acting as if “driven by a motor” (e.g., is unable to be or uncomfortable being still for an extended time, as in restaurants, meetings; may be experienced by others as being restless or difficult to keep up with).

6. Often talks excessively.

7. Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed (e.g., completes people’s sentences; cannot wait for turn in conversation).

8. Often has difficulty waiting their turn (e.g., while waiting in line).

9. Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations, games, or activities; may start using other people’s things without asking or receiving permission; for adolescents and adults, may intrude into or take over what others are doing).

ADHD-C

In order to be diagnosed with ADHD-C based on the DSM-5, one must meet at least six of the ADHD-I criteria of the ADHD-H criteria for the last six months.

Prevalence of the ADHD Subtypes

Given how the prevalence rates ebb and flow throughout the lifespan, it is helpful to think about these subtypes with a bit of fluidity. The diagnosis provided at one specific time may differ from that provided at another specific time in a person’s life. For example, a young child may be diagnosed ADHD-H, and in mid-childhood meet the full criteria for ADHD-C, and in adulthood, only meet the criteria for ADHD-I. Whether a person has ADHD or not, how the symptoms present at a given point in time or a given context has a great deal of flux, and thus it’s helpful to hold the framework of subsets with flexibility.

I found the breakdown of the prevalence throughout the lifespan quite interesting. In a comprehensive metanalysis of ADHD studies Willcutt, 2012 observed the following prevalence rates for ADHD subtypes:

ADHD-I

Preschool: 23% of children with ADHD

Elementary School: 45% of children with ADHD

Adolescence: 72% of teens with ADHD

Adult: 47% of people with ADHD–the most common subtype among adults

ADHD-H

Preschool: 52% of children with ADHD

Elementary: 26% of children with ADHD

Adolescence: 14% of children with ADHD

ADHD- C

Preschool: 25% of children with ADHD

Elementary: 29% of children with ADHD

Declined in samples of adolescents and adults

Similarities and Differences Across ADHD Subtypes

While their presentation differs in several ways–other characteristics are consistent across the board. Some have suggested ADHD-I be considered a separate condition; however, it appears that there is significant enough neuropsychological overlap that ADHD-I should not be treated as a separate disorder. It’s helpful to note that many of the topics below (executive functioning, processing speed) have a lot of variability within the research studies, which speaks to the complexity and variance of ADHD.

Similarities Across ADHD Subtypes

Executive Functioning

The studies on executive functioning (EF) and ADHD subtypes are inconsistent. In the late 1990s, Barkley (1997) hypothesized that ADHD-C and ADHD-H were associated with executive functioning deficits while ADHD-I was not (Geurts et al., 2005). However, this theory has largely fallen out of favor as there is a robust body of research that points to the likelihood that executive functioning challenges are similar across both groups.

(Geurts et al., 2005) studied a group of ADHD-C and ADHD-I children to see if they demonstrated differences in executive functioning and, thus, if they represented distinct disorders. Their findings suggest a similar impact on executive functioning, particularly impairment in inhibition, was noted in both groups.

In a study done by Bahçivan et al., 2015 found similar executive functioning between ADHD-I and ADHD-C on measures of inhibition, set-shifting, verbal fluency, cognitive flexibility, and planning; however, ADHD-I demonstrated significantly higher performances in verbal working memory and verbal category-shifting than children in the ADHD-C group. ADHD-I struggled more with indecision than ADHD-C.

In a study done by Nigg et al, 2002, they compared executive functioning among ADHD-I and ADHD-C and found that the groups did not differ on most domains (ADHD-C struggled with planning more, and motor inhibition was elevated among boys with ADHD-C).

While studies are mixed, it appears there is consensus that similar neuropsychological processes are at play within all subtypes of ADHD, and all experience executive functioning difficulties. However, these will vary from person to person and will likely be influenced by other factors (gender, temperament, presence of co-occurring conditions).

Auditory Processing

Auditory processing disorder is common among ADHDers. In a study done involving ADHD children and adolescence, no difference within auditory processing was found among subtypes (Ghanizadeh, 2009). ADHD children with co-occurring ODD had higher rates of auditorily processing problems and were more likely to under-register sound (hyp0sensitive) (Ghanizadeh, 2009).

Citations

Adalio, C. J., Owens, E. B., McBurnett, K., Hinshaw, S. P., & Pfiffner, L. J. (2018). Processing Speed Predicts Behavioral Treatment Outcomes in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Predominantly Inattentive Type. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 46(4), 701–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0336-z

Arnett AB, Pennington BF, Willcutt EG, DeFries JC, Olson RK. Sex differences in ADHD symptom severity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56:632–639. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12337. [PubMed]

Alloway, T., Elliott, J., & Holmes, J. (2010). The prevalence of ADHD-like symptoms in a community sample. Journal of attention disorders, 14(1), 52–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054709356197

Bahçivan Saydam, R., Ayvaşik, H. B., & Alyanak, B. (2015). Executive Functioning in Subtypes of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Noro psikiyatri arsivi, 52(4), 386–392. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2015.8712

Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological bulletin, 121(1), 65-94. https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0033-2909.121.1.65

Barkley, R. A. (1997). ADHD and the nature of self-control. Guilford press. Google Scholar

Bianchini, R., Postorino, V., Grasso, R., Santoro, B., Migliore, S., Burlo, C., … & Mazzone, L. (2013). Prevalence of ADHD in a sample of Italian students: a population-based study. Research in developmental disabilities, 34(9), 2543-2550.

Bendiksen, B., Svensson, E., Aase, H., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Friis, S., Myhre, A. M., & Zeiner, P. (2017). Co-occurrence of ODD and CD in preschool children with symptoms of ADHD. Journal of attention disorders, 21(9), 741-752.

Bröring T, Rommelse N, Sergeant J, Scherder E. Sex differences in tactile defensiveness in children with ADHD and their siblings. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:129–133. [PubMed]

Fassbender, C., Krafft, C. E., & Schweitzer, J. B. (2015). Differentiating SCT and inattentive symptoms in ADHD using fMRI measures of cognitive control. NeuroImage. Clinical, 8, 390–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2015.05.007

Ghanizadeh A. (2009). Screening signs of auditory processing problem: does it distinguish attention deficit hyperactivity disorder subtypes in a clinical sample of children?. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology, 73(1), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.09.020

Ghanizadeh A. (2011). Sensory processing problems in children with ADHD, a systematic review. Psychiatry investigation, 8(2), 89–94. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2011.8.2.89

Hellwig-Brida S, Daseking M, Petermann F, Goldbeck L. Intelligenz- und aufmerksamkeitsleistungen von jungen mit ADHS [Components of intelligence and attention in boys with ADHD] Zeitschrift Für Psychiatrie, Psychologie Und Psychotherapie. 2010;58:299–308. doi: 10.1024/1661-4747/a000040. [Google Scholar]

Hern KL, Hynd GW. Clinical differentiation of the attention deficit disorder subtypes: do sensorimotor deficits characterize children with ADD/WO? Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1992;7:77–83. [PubMed]

Hunt MG, Bienstock SW, Qiang JK. Effects of diurnal variation on the Test of Variables of Attention performance in young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24:166–172. doi: 10.1037/a0025233. [PubMed]

Kibby, M. Y., Vadnais, S. A., & Jagger-Rickels, A. C. (2019). Which components of processing speed are affected in ADHD subtypes?. Child neuropsychology : a journal on normal and abnormal development in childhood and adolescence, 25(7), 964–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2018.1556625

Nigg, J. T., Blaskey, L. G., Huang-Pollock, C. L., & Rappley, M. D. (2002). Neuropsychological executive functions and DSM-IV ADHD subtypes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(1), 59-66.

Nigg JT, Stavro G, Ettenhofer M, Hambrick DZ, Miller T, Henderson JM. Executive functions and ADHD in adults: Evidence for selective effects on ADHD symptom domains. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:706–717. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.706. [PubMed]

Mayes SD, Calhoun SL, Chase GA, Mink DM, Stagg RE. ADHD subtypes and co-occurring anxiety, depression, and oppositional-defiant disorder: Differences in Gordon Diagnostic System and Wechsler working memory and processing speed index scores. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2009;12:540–550. doi: 10.1177/1087054708320402. [PubMed]

Rossi ASU, de Moura LM, de Mello CB, de Souza AAL, Muszkat M, Bueno OFA. Attentional profiles and white matter correlates in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder predominantly inattentive type. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2015;6:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00122. [PubMed]

Turgay, A., & Ansari, R. (2006). Major Depression with ADHD: In Children and Adolescents. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township)), 3(4), 20–32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2990565/#B4

Weiss, M., Worling, D., & Wasdell, M. (2003). A chart review study of the inattentive and combined types of ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 7(1), 1-9.

Willcutt E. G. (2012). The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, 9(3), 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-012-0135-8