Depression vs. ADHD

Depression and ADHD co-occur at high rates. As Goodman and Thase, 2009 observed: “A significant proportion of adults with mood disorders have comorbid ADHD, and a significant proportion of adults with ADHD have comorbid mood disorders.”

Adults who have escaped diagnosis in childhood will often present to medical providers and therapists with a mood disorder (Daviss and Bond, 2016), as ADHDers who receive late treatment or no treatment have an increased risk of developing a mood disorder. Similar to ADHD and anxiety, ADHDers experience a double vulnerability to depression. On the one hand, there is increased genetic vulnerability to depression, and on the other hand, there is increased environmental vulnerability. Due to experiencing social rejection, peer victimization, and difficulties with school and work, a person may be more vulnerable to developing depression.

In addition to a high level of co-occurrence, the symptoms of one can mimic each other making it difficult to detect the underlying ADHD. Or alternatively, co-occurring depression may be missed as symptoms of depression may be mistaken for ADHD. Treatment for ADHD (stimulants) may cause sleep and appetite changes which can mimic depression, making it difficult to tease out medication side effects vs. depression in children. When both are present, they can exacerbate symptoms of each other; in fact, ADHDers with depression tend to have more prolonged and intensive episodes of depression. Before we delve into the co-occurrence rates, overlapping traits, and implications, below is an overview of depression and ADHD (feel free to skip these two sections if you have a sense of both conditions).

Contents:

ADHD Overview

ADHD is classified as a neurodevelopment condition, meaning the onset occurs during the developmental period (typically early childhood) and has a strong genetic component. The parts of the brain that regulate emotions, attention, and focus are impacted in the context of ADHD. ADHD is characterized by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association 2015). There are three classifications of ADHD a person can be diagnosed with: ADHD-primarily inattentive type, ADHD-primarily hyperactive-impulsive, or combined type.

The Criteria for diagnosing ADHD include the presence of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity (or just inattention in the case of ADHD-inattentive type). The traits must interfere with daily functioning in at least two contexts (for example, home and school or work and home) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some common symptoms of ADHD include:

difficulty focusing or staying on task

problems keeping track of materials

trouble following through on complex projects

distractibility and forgetfulness

appearing not to listen when spoken to

increased need to be up and moving

fidgetiness

impulsivity

tendency to interrupt other people

excessive talking

While present from birth, the symptoms of ADHD may not become apparent until demands exceed capacity. And many children develop sophisticated compensatory strategies to offset areas of struggle. In these cases, even later in life, the person’s ADHD is recognized.

ADHD has a worldwide prevalence of 5.2 % among children and adolescents (Polanczyk et al. 2007). Based on the (CDC), current estimates estimate that 6.1 million children in the U.S. are diagnosed with ADHD, approximately 9.4% of children, making ADHD one of the most commonly diagnosed developmental conditions in the U.S.

Overview of Depression

Depression is characterized by a deep and persistent feeling of sadness and despair. Depression can make it difficult to continue going to work, school, and get up in the morning. A person meets the criteria for clinical depression when five or more of the following symptoms are present during the same 2-week period. This also must mark a significant change from the person’s baseline. And one of the symptoms must include either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure. Symptoms that are attributed to a separate medical condition or substance use are not included (Source: DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective report (e.g., feels sad, empty, hopeless) or observation made by others (e.g., appears tearful). (Note: In children and adolescents, can be irritable mood.)

Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day (as indicated by either subjective account or observation).

Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (e.g., a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month), or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day. (Note: In children, consider failure to make expected weight gain.)

Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day.

Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (observable by others, not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down).

Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day.

Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick).

Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others).

Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide.

To be classified as depression, these symptoms must not result from a significant loss (bereavement, natural disaster, or so forth). Depressive symptoms that came after a tragedy, are proportional to the loss, would better be classified as an adjustment disorder or bereavement. If symptoms are beyond the experiences expected after such a loss, a diagnosis of depression may also be considered in such situations.

Co-Occurrence of ADHD and Depression

Within the medical field, there is growing awareness that ADHD is commonly associated with depression. The depressive symptoms often have a later onset (Riglin et al., 2020). While prevalence rates vary, all studies demonstrate an increased risk of depression among ADHDers. Below is a summary of some of the findings:

Nearly half of ADHD adults had re-occurrent depression (Riglin et al., 2020).

Riglin et al., 2020 found that ADHD increases the risk of depression later in life.

In a study including ADHD children, 41.96% met the criteria for co-occurring anxiety, and 21.43% met the criteria for co-occurring depression (Mitchison & Njardvik, 2019).

There is an estimated 6.5-fold increase in risk for depression within the first year of ADHD diagnosis (Riglin et al., 2020).

Researchers from the University of Chicago found teens who were diagnosed with ADHD between ages 4-6 were 10 times more likely to develop depression than those without ADHD (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2010)

In a study of adults Bron et al. 2016 found that while the prevalence for ADHD was .4 among healthy controls, the prevalence rate went up to 5.6 among those with remitted depression and was as high as 22.1% among adults currently experiencing depression. ADHD rates also significantly increased with severe and chronic depression. And ADHD rates were higher among adults with earlier age of onset of depressive symptoms.

Children diagnosed with ADHD were approximately six times as likely to have depression within one year of ADHD diagnosis and twice as likely within five years, compared to children without ADHD (Gundel et al., 2018)

Implications of Co-Occurring ADHD and Depression

Social and academic impairment is worse among children with ADHD and Depression, but conduct problems were not (Blackman et al., 2005).

When depression co-occurs with ADHD, the depressive episodes tend to be more prolonged and severe (than when not paired with ADHD) and are more likely to include suicidal behaviors and hospitalizations (Daviss and Bond, 2016).

Risk Factors of Co-occurrence

Various risk factors make a person with ADHD more vulnerable to developing co-occurring depression:

Gender

Being female or non-cis increases the chances of co-occurring depression (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2010).

ADHD Inattentive Type

Among (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2010) longitudinal study of early diagnosed ADHD children, those with ADHD-Inattentive type were more likely to have co-occurring depression (also more likely to have co-occurring anxiety).

Undiagnosed/Untreated ADHD

ADHDers had a 20% lower rate of depression when receiving ADHD medication compared to when they were not. Suggesting ADHD medication is associated with a decreased long-term risk of depression (Chang et al., 2016).

Maternal Depression

When mother (or trans-father) were depressed during pregnancy, higher rates of depression, ADHD, and co-occurrence of both were found (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2010).

Early-Onset ADHD

Earlier onset ADHD is associated with an increased risk of depression later in life (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2010).

“Complex” ADHD'

One study found that having co-occurring conditions in childhood (ODD/conduct disorder) was associated with an increased risk of developing depression in teenage years than children with “uncomplicated ADHD” (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2010).

Etiology of co-occurrence

There appears to be considerable genetic overlap between ADHD and depression (Riglin et al., 2020). Genetics play a role in the high co-occurrence rate between ADHD and depression. Among twin studies, the co-occurrence of ADHD and depression demonstrated significant genetic factors (approximately 70%) (Faraone and Larsson, 2019).

Riglin et al., 2020 found that the association between adult ADHD and depression was not driven by childhood depression but rather was better explained by the continuation of ADHD into adulthood.

Earlier pharmacological treatment of ADHD is associated with a reduced risk of MDD (Daviss et al., 2008).

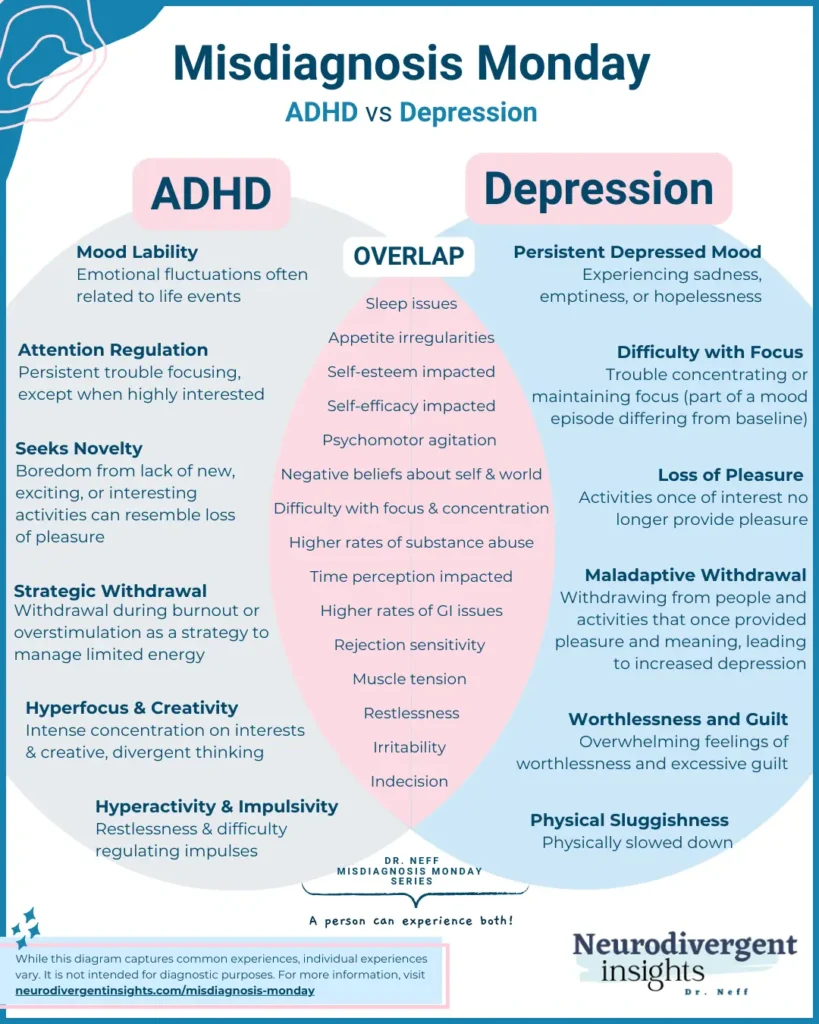

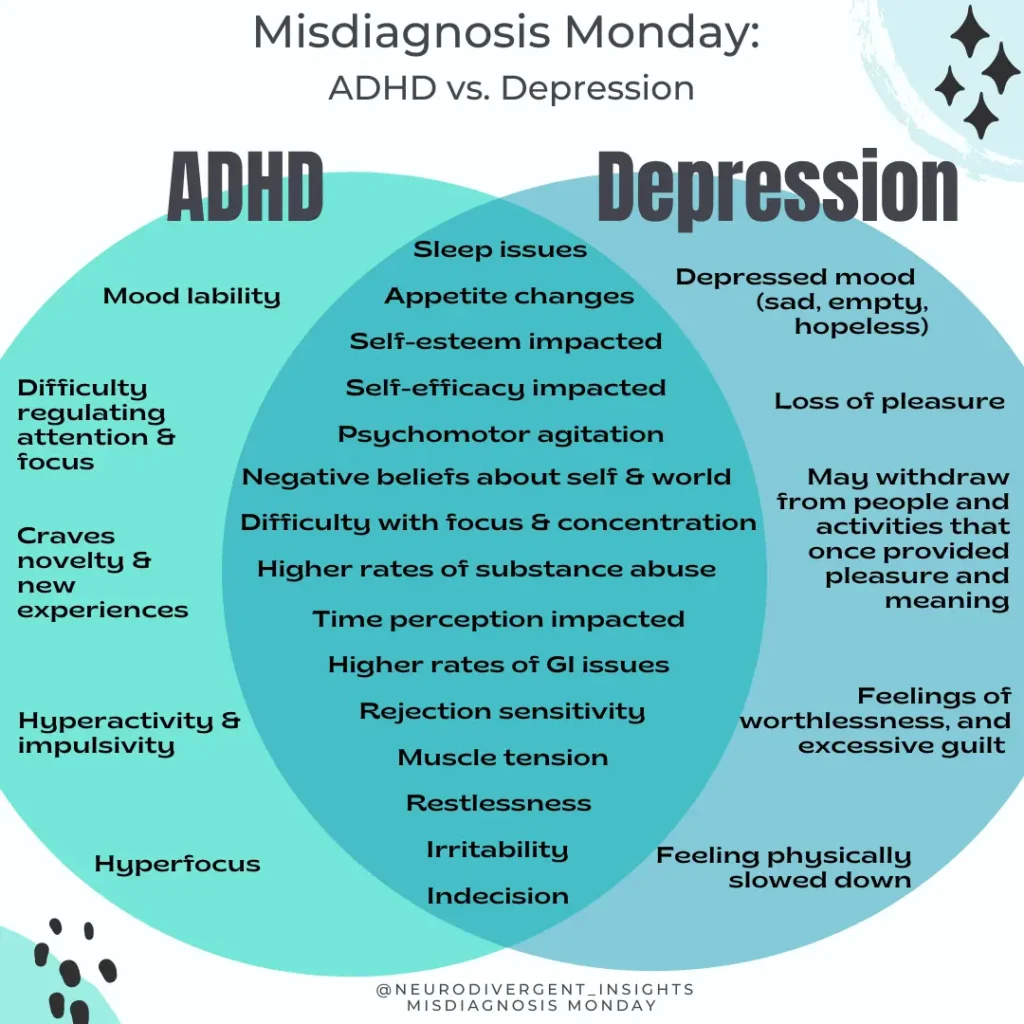

Overlapping Traits

Focus and Concentration

Difficulty with focus is common among ADHDers. Difficulty with focus and concentration is also a feature of depression.

Motivation Difficulties

Due to an interest-based nervous system, many ADHDers struggle with regulating motivation for routine tasks. Motivation is also impacted in the context of depression and simple tasks may feel tedious and difficult to initiate and complete.

Appetite

ADHD and medication for ADHD can cause disruptions to appetite and eating patterns. Changes to appetite, and eating patterns are also core features of depression.

Self-Esteem/Self-Worth

A key feature of depression is a loss of self-esteem and a sense of worthlessness. Many people with ADHD also struggle with self-esteem issues because they receive more negative feedback, and many experiences more challenge and struggles in daily tasks. To distinguish ADHD self-esteem from depression worthlessness, the clinician would want to understand whether the current experience is similar to the person’s baseline sense of self.

Mood

It is common for ADHDers to experience mood lability. Mood lability is more likely to be in reaction to an external stressor (experiencing social rejection or performing poorly in school or work). With depression, the person will experience a pervasive and consistent period of depression lasting at least two weeks. There often is not a concrete external stressor that causes the depressed mood (such as in the case of mood lability).

Sleep issues

People with ADHD commonly have co-occurring sleep issues. Despite being fatigued, people with depression frequently experience co-occurring sleep issues. It is common to experience insomnia and early waking in the context of depression. Poor sleep will also impact executive functioning skills (focus, concentration, decision-making), making it more challenging to tease out the difference.

Executive Functioning Difficulties

When depressed, a person’s executive functioning is often impacted. The ability to make decisions, focus, access motivation, and more are impacted in the context of depression (Fossati et al., 2002). These are key features of ADHD.

Agitation and Irritability

Agitation, irritability, and increased difficulty regulating intense emotions are commonly associated with ADHD (Eyre et al., 2017). Agitation and irritability are less known characteristics of depression. Balbuena et al. (2016) suggested that mood instability and irritability should be considered as core symptoms of depression and should be included in clinical assessment for depression. Eyre et al. 2017 further found that irritability rates were highest amongst ADHD children with co-occurring mood disorders.

Working Memory

Working memory is often inconsistent in the context of ADHD. Depression was also associated with a distinct cognitive profile and can negatively impact working memory (Christopher and MacDonald, 2005).

How to Spot the Difference

1) For adults: when diagnosing depression, particularly severe, chronic, and treatment-resistant depression, do a careful and thorough childhood history to rule out the possibility of undiagnosed ADHD. As Daviss and Bond, (2016) note:

“Adults with ADHD often present with chief complaints of mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders, rather than ADHD. The key to diagnosing ADHD in patients who have depression is to carefully consider their childhood history to determine whether symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity were evident before the depression.” Daviss and Bond, 2016).

2) When diagnosing children: According to Daviss and Bond, (2016) the symptoms the best distinguish depression from ADHD are the presence of

Depressive cognitions (e.g., guilt, worthlessness, hopelessness, morbid or suicidal thoughts)

Severe anhedonia

Psychomotor retardation (slowing of bodily movements).

While symptoms such as irritability, poor concentration, anergia, sleep problems, and psychomotor or appetite changes are less helpful because they overlap with ADHD, the side effects of ADHD medications (Daviss and Bond, 2016).

3) Consider routinely screening for both (although be aware the presence of one may cause false elevations on the screener for the other, especially items that have about concentration, focus, restlessness, and sleep). So consider using routine screeners and interpreting them contextually.

Patient Health Questionnaire (Screener for depression)

Treatment

Following are some treatment considerations when considering co-occurring depression and ADHD.

Riglin et al., 2020 suggest it is vital clinicians be aware that up to 50% of adults with ADHD have co-occurring depression as this may remain undiagnosed at high rates.

Treatment of ADHD decreases the risk of co-occurring depression, and earlier pharmacological treatment of ADHD is associated with a reduced risk of MDD (Daviss et al., 2008).

Stimulant pharmacotherapy is generally the first-line treatment for uncomplicated ADHD (Daviss and Bond, 2016), and psychotherapy and an SSRI (anti-depressant) are typically first-line treatments for depression.

A combination of medications (stimulants or non-stimulant medication for ADHD), antidepressants (for depression), psychotherapy, and executive functioning coaching can help reduce the suffering and difficulties associated with both conditions.

Treating ADHD will often help reduce the stress associated with ADHD, which can help improve mood. And vice versa treating depression will help improve executive functioning and motivation difficulties associated with ADHD.

Vitamins that can support ADHD and Depression (always recommended to check with a medical provider and do your own research before starting a new vitamin regimen): Fish Oil, Rainbow Light Brain and Focus supplement, Hemp Gummies, Melatonin (to help with sleep).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Balbuena, L., Bowen, R., Baetz, M., & Marwaha, S. (2016). Mood Instability and Irritability as Core Symptoms of Major Depression: An Exploration Using Rasch Analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 7, 174. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00174

Blackman, G. L., Ostrander, R., & Herman, K. C. (2005). Children with ADHD and depression: a multisource, multimethod assessment of clinical, social, and academic functioning. Journal of attention disorders, 8(4), 195-207.

Bron, T. I., Bijlenga, D., Verduijn, J., Penninx, B. W., Beekman, A. T., & Kooij, J. J. (2016). Prevalence of ADHD symptoms across clinical stages of major depressive disorder. Journal of affective disorders, 197, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.053

Chang, Z., D’Onofrio, B. M., Quinn, P. D., Lichtenstein, P., & Larsson, H. (2016). Medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk for depression: A nationwide longitudinal cohort study. Biological Psychiatry, 80(12), 916–922. PubMed

Christopher, G., & MacDonald, J. (2005). The impact of clinical depression on working memory. Cognitive neuropsychiatry, 10(5), 379-399.

Chronis-Tuscano, A., Molina, B. S., Pelham, W. E., Applegate, B., Dahlke, A., Overmyer, M., & Lahey, B. B. (2010). Very early predictors of adolescent depression and suicide attempts in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 67(10), 1044–1051. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.127

Daviss, W. B., & Bond, J. B. (2016). Comorbid ADHD and depression: assessment and treatment strategies. Psychiatr Times, 33(9).

Daviss WB, Birmaher B, Diler RS, Mintz J. Does pharmacotherapy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder predict risk of later major depression? J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2008;18:257-264.

Eyre, O., Langley, K., Stringaris, A., Leibenluft, E., Collishaw, S., & Thapar, A. (2017). Irritability in ADHD: Associations with depression liability. Journal of affective disorders, 215, 281–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.050

Faraone, S. V., & Larsson, H. (2019). Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Molecular psychiatry, 24(4), 562–575. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0070-0

Fossati P, Ergis AM, Allilaire JF (2002). Executive functioning in unipolar depression: a review. L’encephale, 2: 97-107. PMID: 11972136.

Goodman, D. W., & Thase, M. E. (2009). Recognizing ADHD in adults with comorbid mood disorders: implications for identification and management. Postgraduate medicine, 121(5), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2009.09.2049

Gundel, L. K., Pedersen, C. B., Munk-Olsen, T., & Dalsgaard, S. (2018). Longitudinal association between mental disorders in childhood and subsequent depression – A nationwide prospective cohort study. Journal of affective disorders, 227, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.023

Mitchison, G. M., & Njardvik, U. (2019). Prevalence and gender differences of ODD, anxiety, and depression in a sample of children with ADHD. Journal of attention disorders, 23(11), 1339-1345.

Polanczyk, G., de Lima, M. S., Horta, B. L., Biederman, J., & Rohde, L. A. (2007). The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. The American journal of psychiatry, 164(6), 942–948. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942

Riglin, L., Leppert, B., Dardani, C., Thapar, A., Rice, F., O’Donovan, M., . . . Thapar, A. (2021). ADHD and depression: Investigating a causal explanation. Psychological Medicine, 51(11), 1890-1897. doi:10.1017/S0033291720000665