ADHD vs. Tourette Syndrome

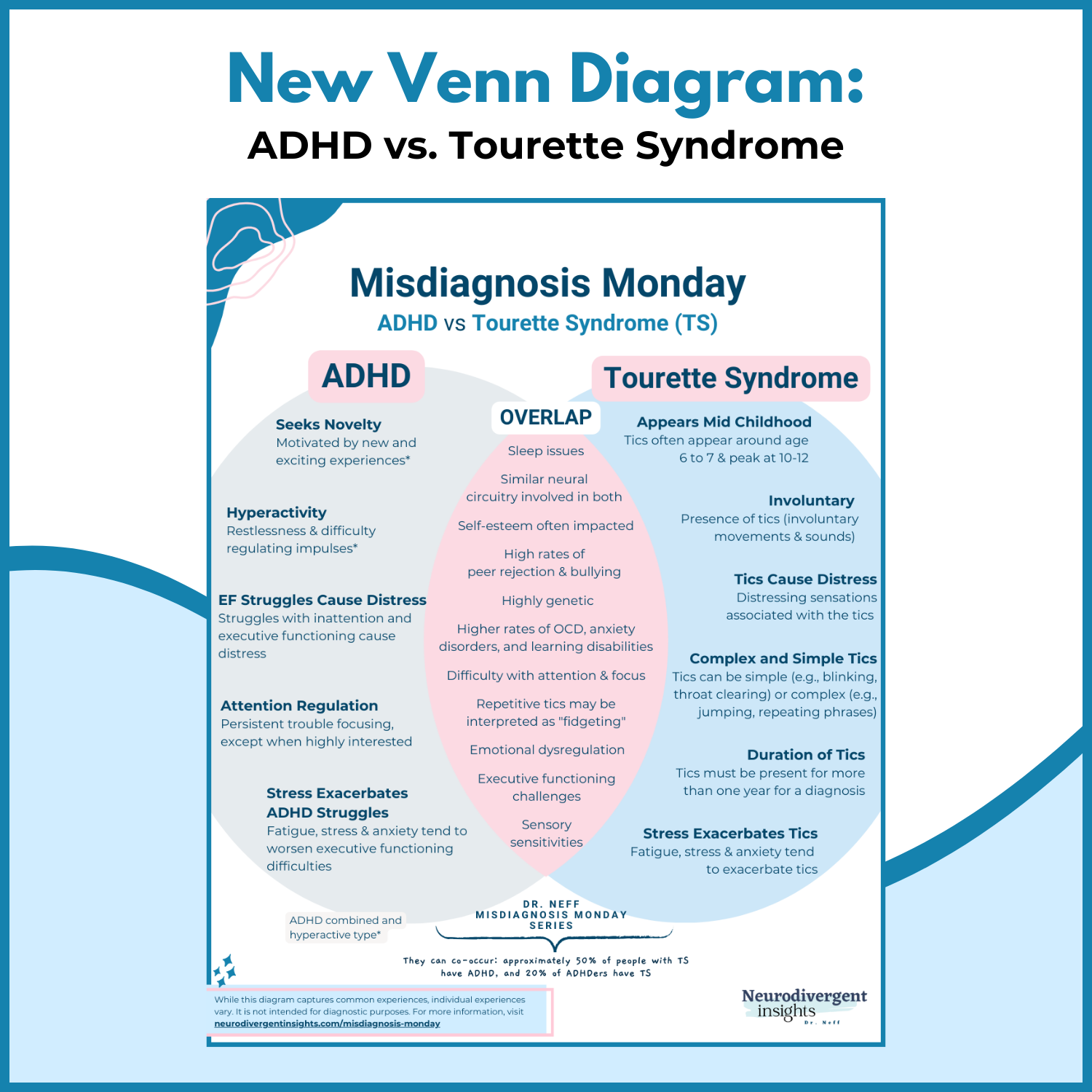

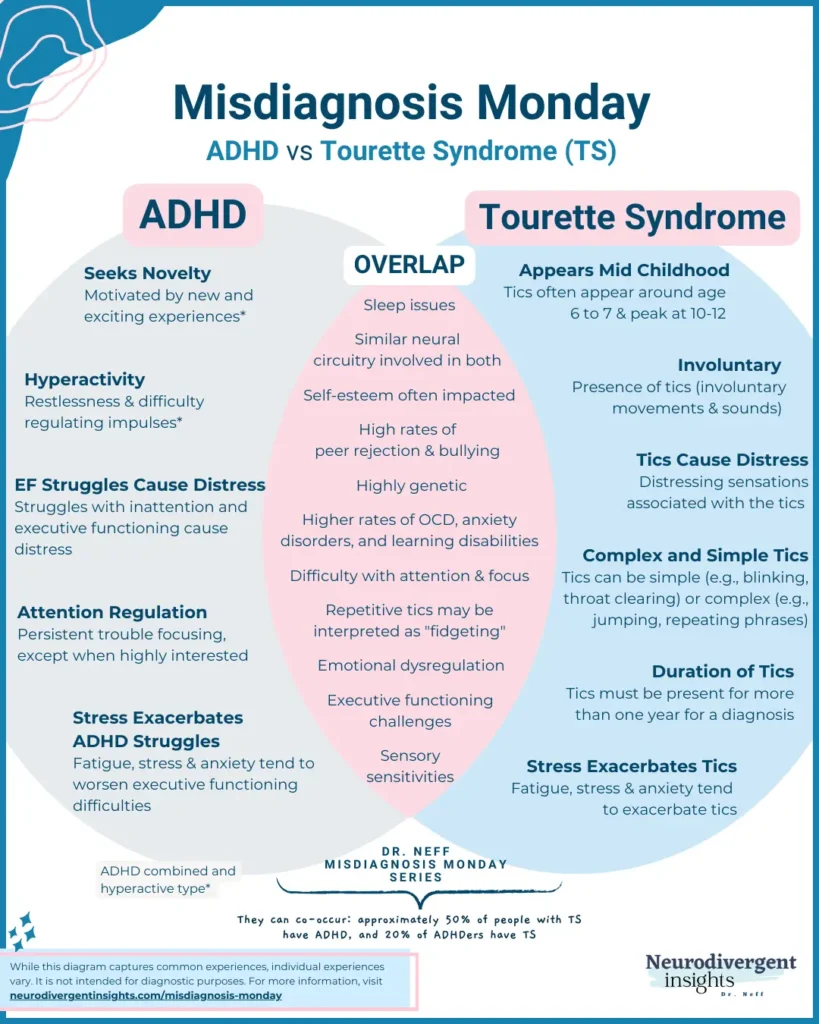

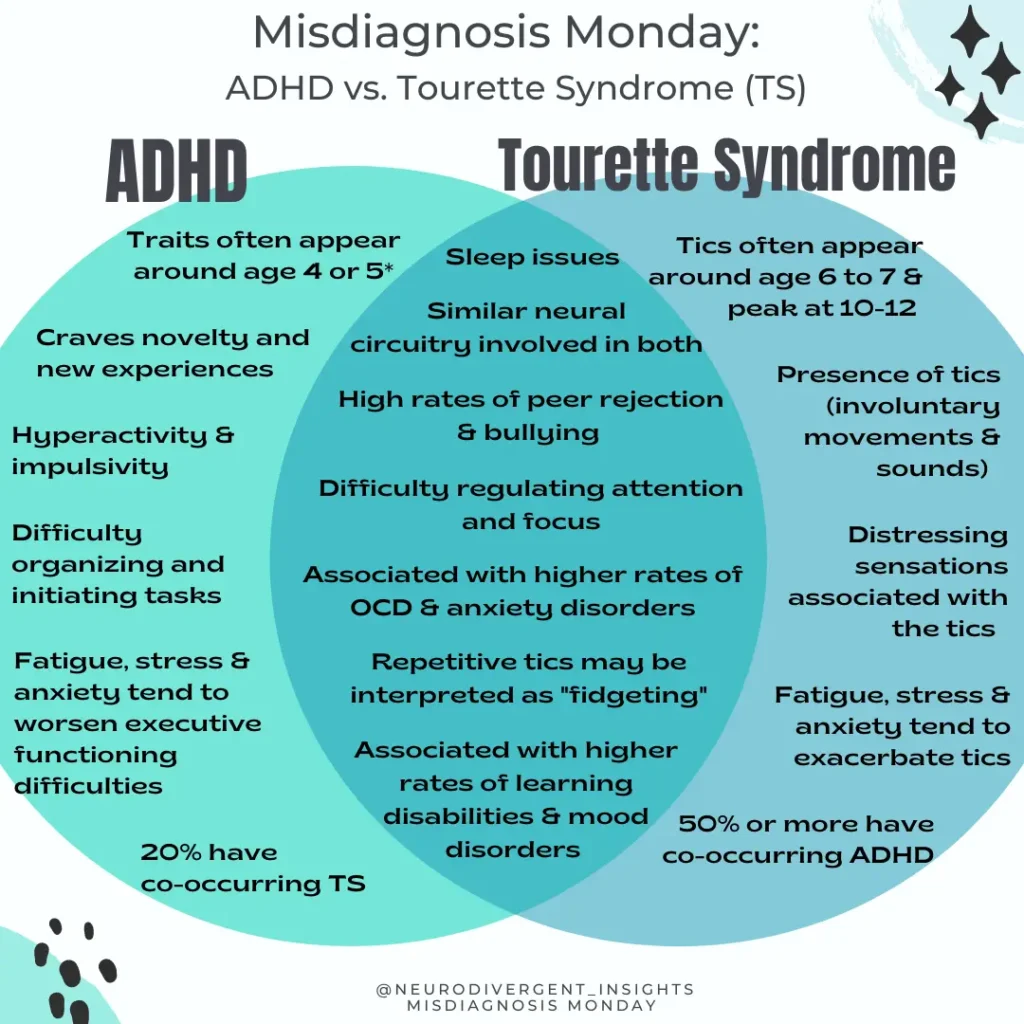

While I’m taking on the conversation of Tourette Syndrome and ADHD as part of my #MisdiagnosisMonday series, perhaps Tourette Syndrome and ADHD would be better discussed as part of a series on “co-occurring conditions”. While the overlap of these conditions may cause one diagnosis to be missed, or in some cases, TS may be misdiagnosed as ADHD, it is more common that these conditions co-occur.

Both are considered neurodevelopmental disorders and appear in childhood. TS is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by experiencing multiple chronic motor and vocal tics (non-voluntary or semi-voluntary sounds and movements). ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by difficulty regulating attention and focus, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Before diving into the overlap and the implications for co-occurrence, first, a brief overview of each condition (Feel free to skip the following two sections if you’re familiar with both conditions).

ADHD Overview

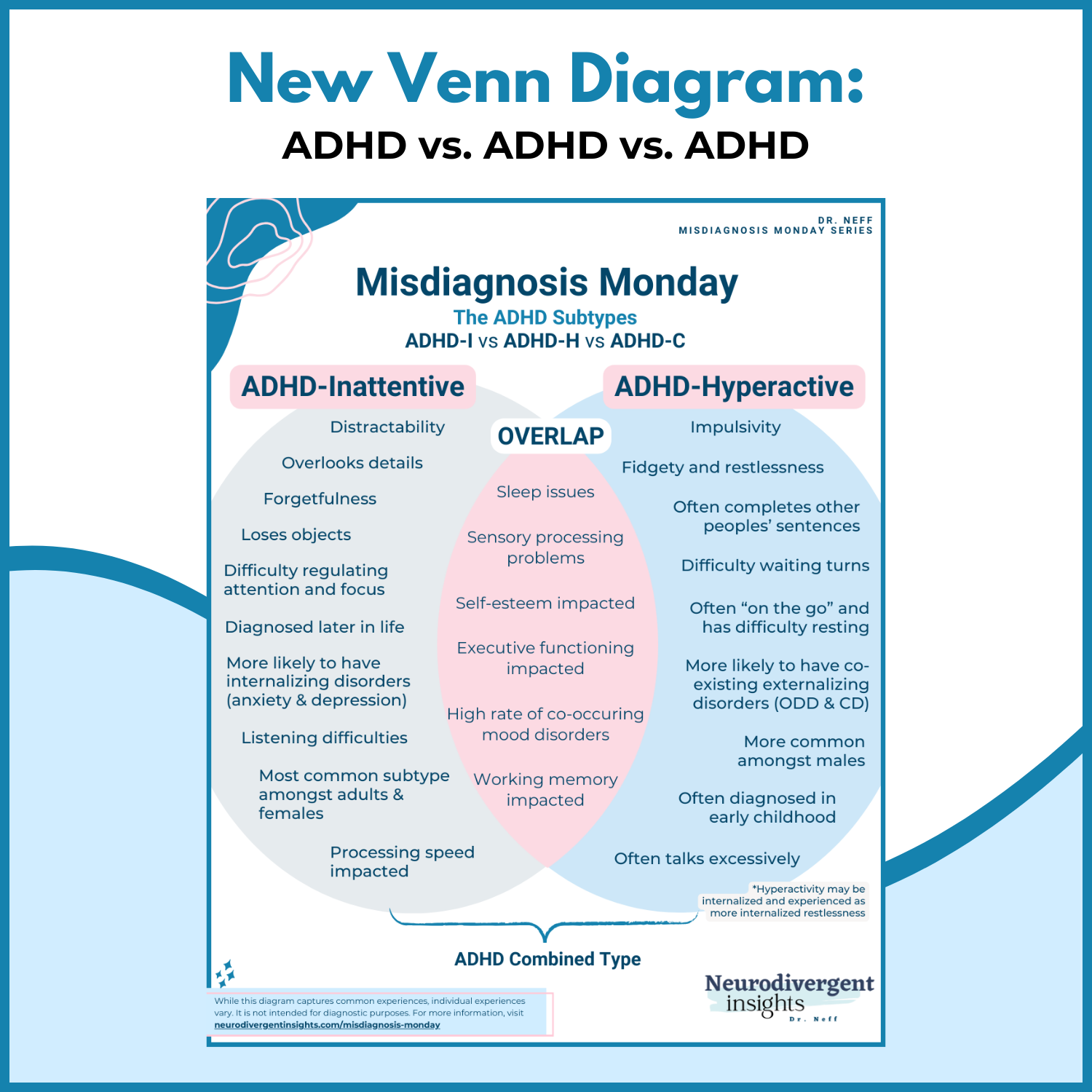

ADHD is classified as a neurodevelopment condition, meaning the onset occurs during the developmental period (typically early childhood) and has a strong genetic component. The parts of the brain that regulate emotions, attention, and focus are impacted in the context of ADHD. ADHD is characterized by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2015). There are three classifications of ADHD a person can be diagnosed with: ADHD-primarily inattentive type, ADHD-primarily hyperactive-impulsive, or combined type.

The Criteria for diagnosing ADHD include the presence of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity (or just inattention in the case of ADHD-inattentive type). These characteristics must interfere with daily functioning in at least two contexts (for example, home and school or work and home) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Some common traits of ADHD include:

difficulty focusing or staying on task

problems keeping track of materials

trouble following through on complex projects

distractibility and forgetfulness

appearing not to listen when spoken to

increased need to be up and moving

fidgetiness

impulsivity

tendency to interrupt other people

excessive talking

While present from birth, ADHD may not become apparent until demands exceed capacity. And many children develop sophisticated compensatory strategies to offset areas of struggle. In these cases, ADHD may not be recognized until late in life.

ADHD is the most common childhood psychiatric condition, with an estimated prevalence of 2% to 15% (Robertson, 2008). ADHD has a worldwide prevalence of 5.2 % among children and adolescents (Polanczyk et al. 2007). Based on the (CDC), current estimates estimate that 6.1 children in the U.S. are diagnosed with ADHD, approximately 9.4% of children, making ADHD one of the most commonly diagnosed developmental disorders in the U.S.

Tourette Syndrome Overview

Tourette syndrome is often portrayed in an exaggerated and unflattering way in media and culture, leading to misperceptions of TS. Unfortunately, this means it may go unrecognized and undiagnosed in many individuals (Contemporary Pediatrics).

TS is characterized by the presence of chronic motor and vocal tics. Tics are sudden, rapid, and often recurrent and non-rhythmic involuntary movements or vocalizations. Tics can be simple (one body part) or complex (involving several muscle groups). Examples include eye blinking, shoulder shrugging, head jerking, hand-clapping, neck stretching, mouth movements, head, arm, or leg jerks, and facial grimacing. Vocal tics, or phonic tics, are involuntary sounds; examples may include: clearing of the throat, repeating meaningless words, syllables or phrases, echolalia, or coprolalia (compulsive utterance of obscene words) (Oluwabusi et al., 2016).

Typical onset is around the age of 6-7, and the symptoms tend to peak between the age of 10-12 (Oluwabusi et al., 2016). (To see the typical clinical trajectory/timeline of TS, see this chart here). Tics naturally wax and wane over minutes, days, weeks, and even months. They often increase during times of stress, fatigue, and anxiety, and when individuals attempt to suppress tics over a prolonged period. Contemporary Pediatrics).

To be diagnosed with TS, a person must have both motor tics and one or more vocal tics; however, they do not need to be occurring concurrently. They must occur multiple times a day, nearly every day, or intermittently. They must have been present for over a year and cannot be induced by other substances or other medical conditions (such as Huntington’s disease).

Tic disorders and TS commonly co-occur with other conditions, including ADHD, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), learning difficulties, and sleep disorders Oluwabusi et al., 2016.

Co-occurrence of ADHD and Tourette Syndrome

ADHD and TS co-occur at high rates and have additional risks when both are present.

Prevalence

ADHD traits are reported in 35-90% of children with TS (Oluwabusi et al., 2016).

ADHD is the most common co-occurring condition with TS (Oluwabusi et al., 2016).

It is estimated that 1 in 5 or 20% of ADHD children will develop a chronic tic disorder. (Bloch, 2009).

Half or more of children with TS are also ADHD (Freeman, 2007).

Implications of Co-occurrence:

When they co-occur, signs of ADHD typically emerge before the onset of tics (Oluwabusi et al., 2016). This is one reason why the emergence of tics may have been falsely attributed to the use of stimulant medication for many years.

When a child has both, they may exert extra energy and attention, attempting to suppress their tics; this can exacerbate difficulties with regulating attention and focus (Contemporary Pediatrics).

ADHD children and TS children are both vulnerable to anxiety disorders and OCD. Children who are both ADHD and have TS have even high rates of OCD and generalized anxiety disorders than children with just one of the conditions. Complicating matters, those with anxiety disorders have additional risks of developing depression. Thus, monitoring for mood disorders and OCD should be routine when a child has both. (Contemporary Pediatrics).

Children with both ADHD and TS tend to have more psychosocial and behavioral difficulties than ADHD or TS-only groups (Oluwabusi et al., 2016).

Children with both conditions tend to have more social difficulties and are more likely to be bullied than those who have Tourette disorder alone and who have cognitive and other neuropsychiatric impairments. (Contemporary Pediatrics)

Children with both are more prone than children with TS alone to have anxiety and depression and to demonstrate more “maladaptive behaviors,” including “aggression and delinquency.” (Contemporary Pediatrics).

Overlapping Traits

In addition to co-occurring at high rates, several overlapping traits may result in one diagnosis being missed, or, on rare occasions, TS may be misdiagnosed as ADHD.

Sleep Issues

Sleep disorders and sleep issues are common among both groups. Sleep studies show approximately 80% of people with TS have sleep problems and an approximately 30% reduction in delta sleep (slow-wave sleep) and decreased REM sleep. (Sandyk et al., 1987). Similarly, high rates of sleep problems are reported among ADHDers. Approximately 25-50% of ADHDers struggle with circadian rhythm sleep disorders, insomnia, narcolepsy, restless leg syndrome, sleep-disordered breathing, and insomnia (Wajszilber et al., 2021). Nightmares and insomnia are also common among ADHD children (Grünwald and Schlarb, 2017). And up to 70% of children with ADHD have sleep difficulties (Sciberras, 2020).

Disinhibitory Circuits

Both TS and ADHD share similar genetic and neurological overlaps. For example, similar neural circuitry, which is involved in disinhibition, is involved in both conditions (Contemporary Pediatrics). For those interested in understanding the various neurological circuits involved, see the following excerpt from (Contemporary Pediatrics)

“Most specifically, impulsive actions in ADHD (sudden and unpremeditated, unfiltered behaviors often prompted by a sense of urgency) and tics (sudden stereotyped movements or noises usually prompted by unpleasant warning sensations) may suggest a neural circuitry “disinhibition,” or release, of undesired patterns of behavior linked to emotion, sensation, movement, and cognition.

The physiologic model of disinhibition centers largely on dysfunction in monoamine neurotransmitter systems in communications among the basal ganglia, the frontal and other cortex regions, and the thalamus. The mechanism has not been fully characterized, but ongoing epidemiologic, pathophysiologic, and genetic investigations support the relationship between ADHD and tics, as well as other related neurodevelopment disorders of disinhibition including obsessions and compulsions, anxiety, and “rage” attacks.”

Inattention

With tics, most children and adolescents can point to a sensation occurring right before the tic that serves as a sort of forewarning. These sensations are often described as urges, pressure, tension, or an itch. These tend to be distracting and unpleasant in nature (Contemporary Pediatrics). These uncomfortable sensations are relieved through engaging in the semi-voluntary tic. This can cause the child to become distracted by these sensations, resulting in difficulty regulating attention. Furthermore, if a child is trying to suppress tics, this takes a great deal of attention and can result in emotional stress and attention and focus difficulties. Thus a child with TS may present as inattentive, but it may be largely driven by the distraction of the physical sensations and efforts to suppress involuntary tics.

Fidgeting/Hyperactivity vs. Repetitive Tics

Tics can present as repetitive, and a person may have a series of single repetitive tics. This may present as fidgetiness or hyperactivity (Taylor, 2009)

While many children with TS do have ADHD, it is also possible that a child with TS may be mistakenly diagnosed with ADHD for the reasons identified above. In order to differentiate these conditions, it’s essential to understand the causes of inattention and be able to evaluate what attention and focus look like in the absence of tics.

Treatment Implications for Co-Occurrence

Management of TS Tends to Improve Quality of Life

Management of TS among ADHDers can improve quality of life and improve executive functioning difficulties. And vice versa—ADHD treatment can reduce overall stress and anxiety, which may reduce the prevalence of tics (Oluwabusi et al., 2016).

Treat ADHD First

Difficulties associated with ADHD typically lead to the most significant problems, so it is generally recommended to treat ADHD first. Effective treatments of ADHD may help reduce tic severity, as improvement in mental focus and attention may reduce stress, anxiety, and worry. On rare exceptions, it’s beneficial to treat TS first. Children whose tics are leading to significant interference with attention and focus are experiencing pain or whose tics threaten self-injury would benefit from immediate intervention targeting tic reduction (Contemporary Pediatrics).

Consider Co-Occurring Conditions

Clinicians should be aware of other frequent co-occurring conditions such as aggression, oppositional behavior, mood disorders, specific learning disabilities, and sleep disturbances. These common co-occurring conditions can strain the child, resulting in increased executive functioning difficulties, leading to more challenging behaviors, such as more aggression and opposition (Contemporary Pediatrics).

Medication Considerations

As Oluwabusi et al., 2016 observed: “There is a misperception that stimulants are contraindicated in patients with tic disorders due to the potential to cause or exacerbate tic. However, the role of stimulants in the treatment of TS, when the benefits outweigh the risks, cannot be over-emphasized.”

Historically there has been the perception that stimulant medication exacerbates or causes tics, causing many providers to be cautious about prescribing stimulant medication for children with both. However, upon further study, these suspicions have been proven to be largely unfounded (Contemporary Pediatrics). Beginning in the 1980s, several rigorous, well-controlled studies, despite the conventional idea that stimulants caused tics these studies consistently failed to demonstrate a reliable association Contemporary Pediatrics). Recent studies report that short-term use of stimulant medications, especially methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta), seems to be safe and well-tolerated in ADHD children with TS (CHADD)

Follow-up Resources

Below are a few helpful resources for TS; in addition to these, the Tourette Syndrome Association (www.tsa-usa.org) and Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (www.chadd.org) are two organizations that provide several helpful resources that cover the topic of self-advocacy, supporting education needs and medical care.

Citations

Bloch MH, Panza KE, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Leckman JF. Meta-analysis: treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with comorbid tic disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009; 48(9):884-893.

Freeman RD; Tourette Syndrome International Database Consortium. Tic disorders and ADHD: answers from a world-wide clinical dataset on Tourette syndrome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(suppl 1):15-23. Erratum in: Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(8):536.

Grünwald, J., & Schlarb, A. A. (2017). Relationship between subtypes and symptoms of ADHD, insomnia, and nightmares in connection with quality of life in children. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 13, 2341–2350. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S118076

Oluwabusi, O. O., Parke, S., & Ambrosini, P. J. (2016). Tourette syndrome associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The impact of tics and psychopharmacological treatment options. World journal of clinical pediatrics, 5(1), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v5.i1.128

Robertson M. M. (2000). Tourette syndrome, associated conditions and the complexities of treatment. Brain : a journal of neurology, 123 Pt 3, 425–462. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/123.3.425

Sandyk, R., Bamford, C. R., & Iacono, R. P. (1987). Sleep disorders in Tourette’s syndrome. The International journal of neuroscience, 37(1-2), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.3109/00207458708991801

Scriberras, E. (2020) How Can We Help Children with ADHD Get a Better Night’s Sleep? CHADD retrieved at: https://chadd.org/attention-article/how-can-we-help-children-with-adhd-get-a-better-nights-sleep/

Taylor E. Sleep and tics: problems associated with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(9):877-878.

Wajszilber, D., Santiseban, J. A., & Gruber, R. (2018). Sleep disorders in patients with ADHD: impact and management challenges. Nature and science of sleep, 10, 453–480. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S163074