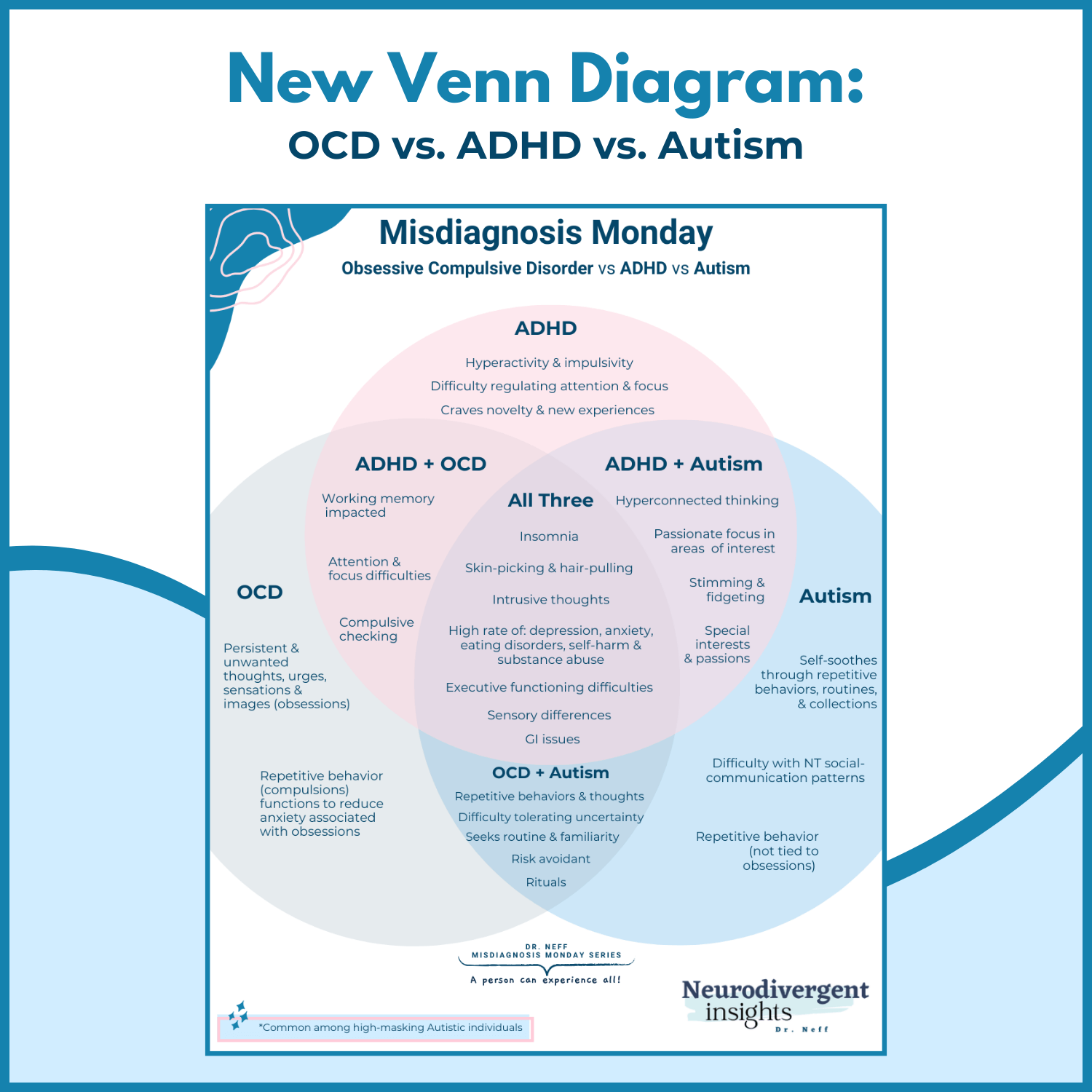

OCD VS. Autism

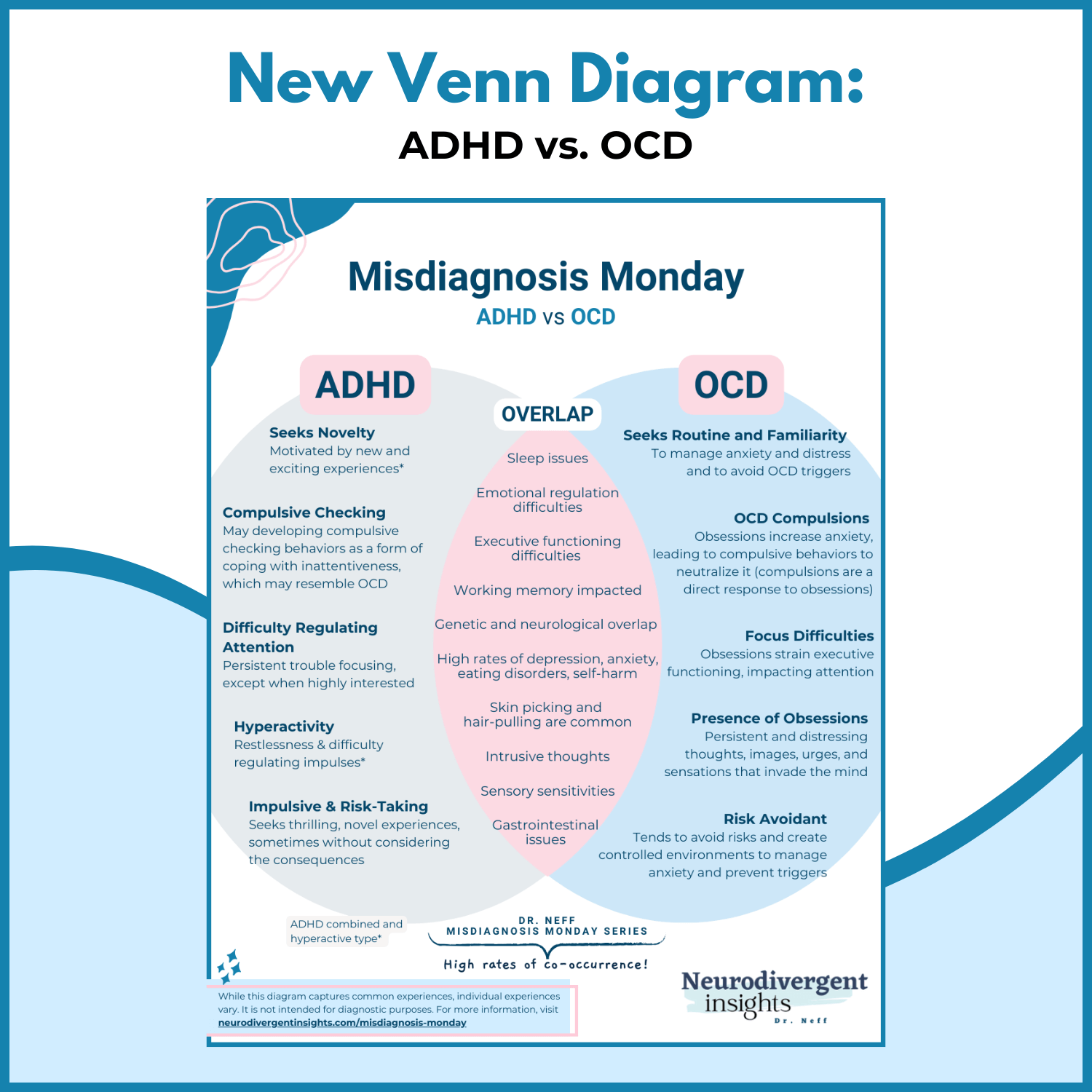

This week I’m tackling another misdiagnosis that may be better situated as an “And” conversation. OCD and Autism go together quite frequently. While there is undoubtedly characteristic overlap (Autistic repetitive behavior can look like OCD compulsions and rituals and vice versa), there is increasing evidence that these conditions are

a) distinct from one another

b) co-occur at high rates.

Based on emerging research, there is reason to believe there are many people with OCD who likely have undiagnosed Autism. Hence, it’s certainly still a relevant conversation to this misdiagnosis series.

Given the significant overlap, it can be challenging to tease out the difference (and co-occurrence). This raises the risk of being diagnosed with one while the other condition goes undiagnosed and untreated/unsupported (Yuhas, 2019).

Contents:

Co-Occurrence of OCD and Autism

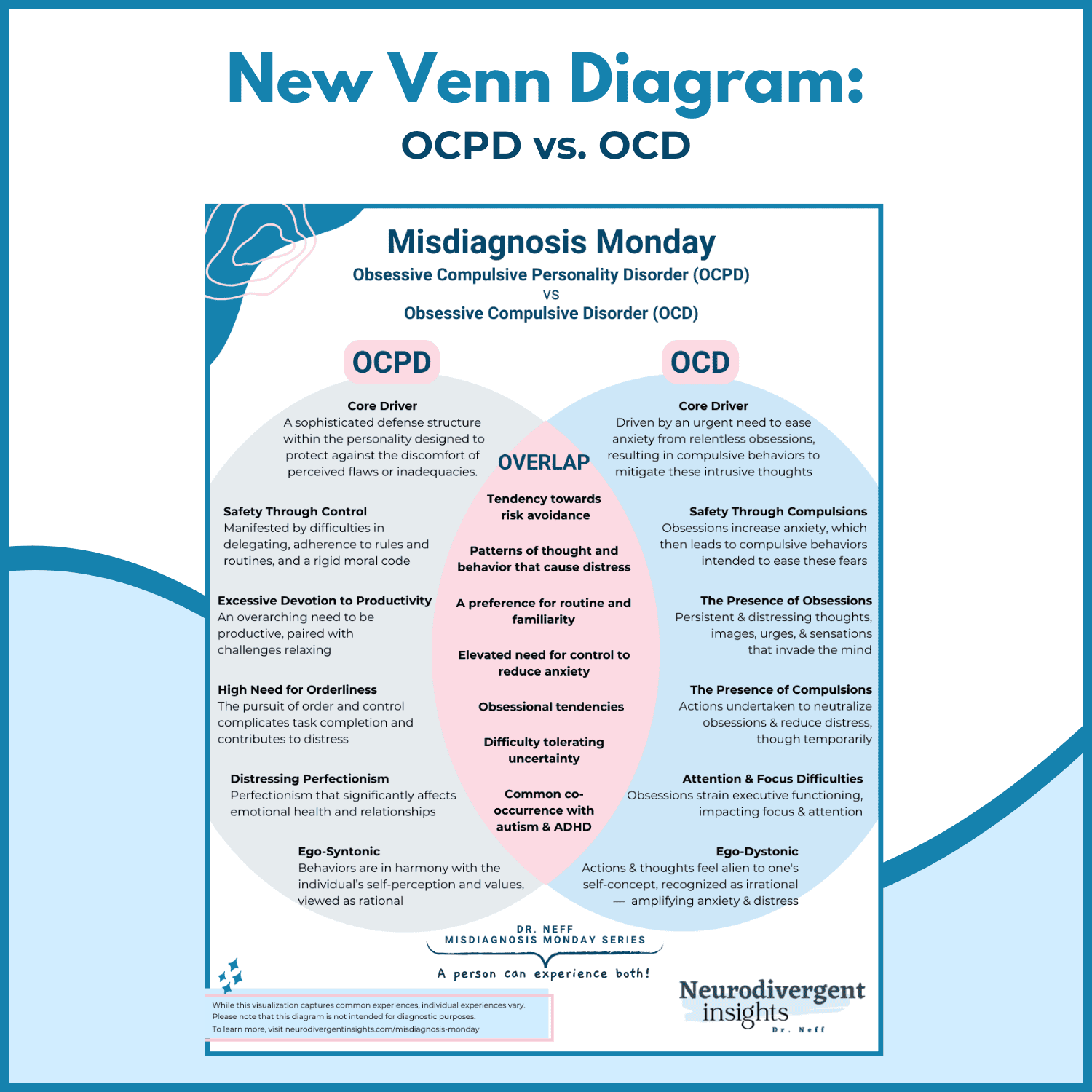

OCD is characterized by persistent distressing thoughts, ideas, or sensations that cause significant fear and anxiety (obsessions), followed by specific behaviors such as handwashing and door checking (compulsions) intended to reduce the obsessions. It must impact daily functioning and take up significant portions of a person’s life (one hour) (American Psychiatric Association).

Obsessive and intrusive thoughts tend to cluster around similar themes. Some common obsessions include:

Fear of contamination

Worries about having left appliances on or doors unlocked

Fear of acting in shameful or humiliating ways

Discomfort with things being out of order

Sexual imagery

Hypochondriac and health anxiety

Excessive thoughts regarding religion/guilt/shame and purity

Some common compulsions include:

Excessive cleaning and handwashing,

Repeating checking doors, locks, appliances

Rituals designed to ward off contact with superstitious objects

Arranging and rearranging objects

Using prayers or chants to prevent bad things from happening

Hoarding

Source Brem et al., 2014

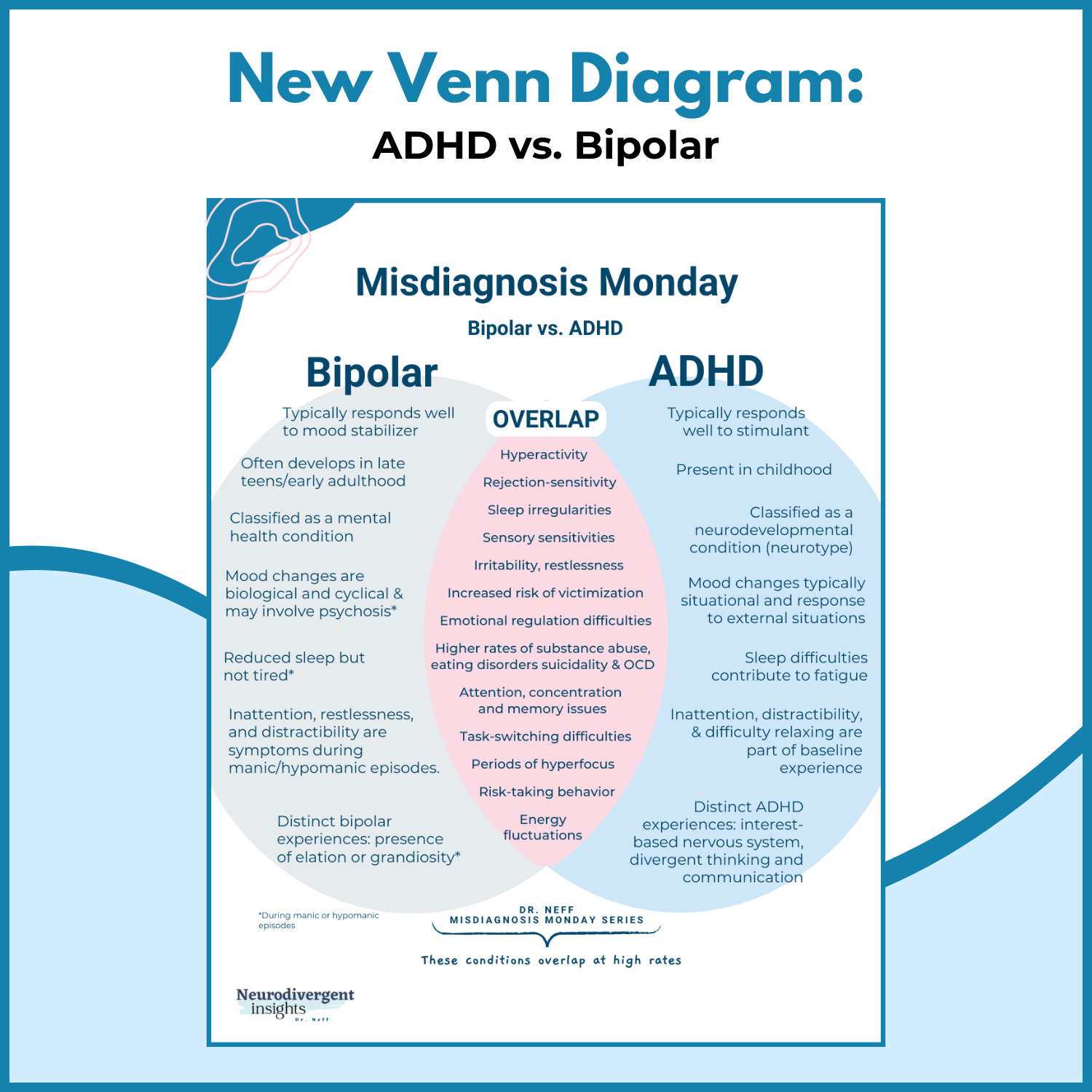

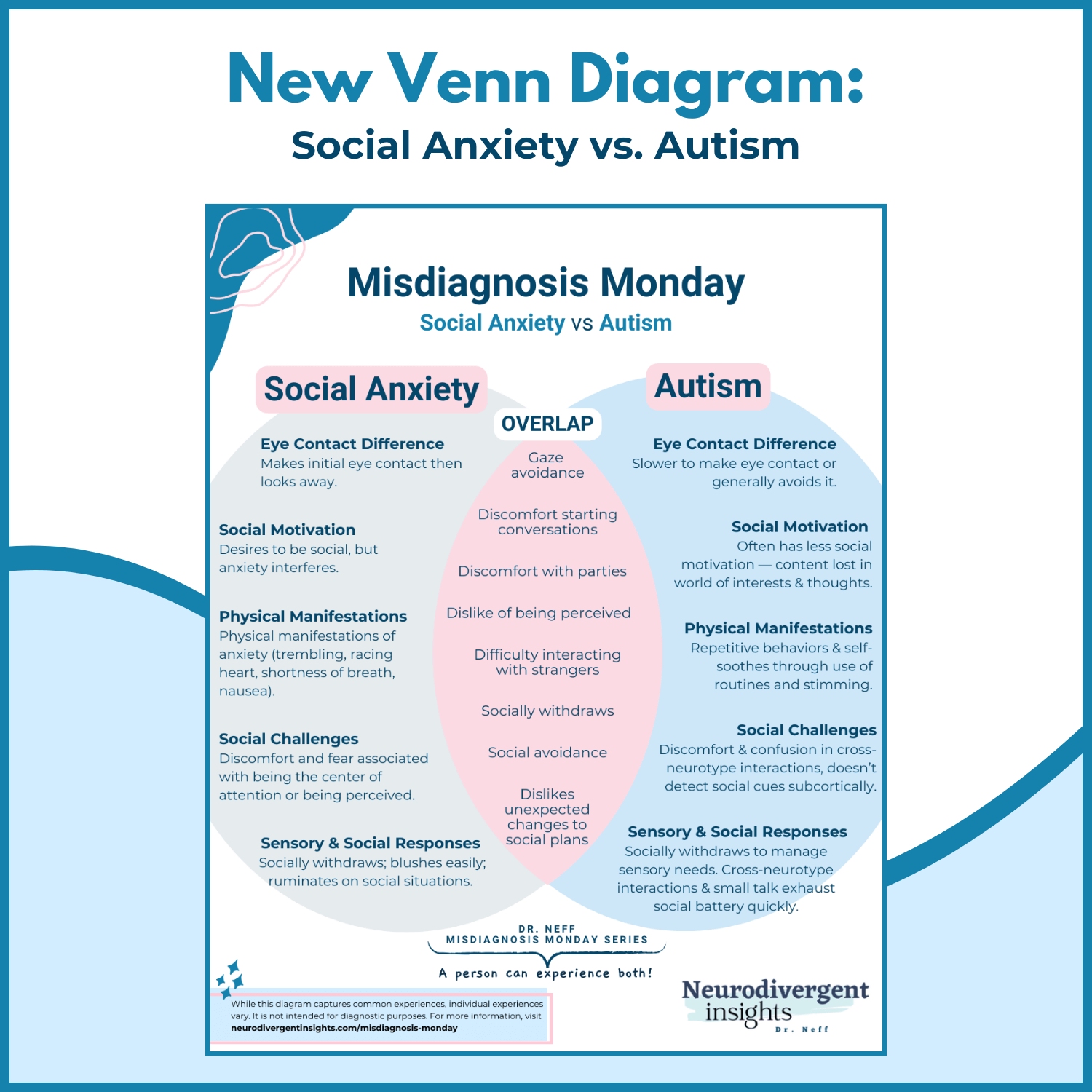

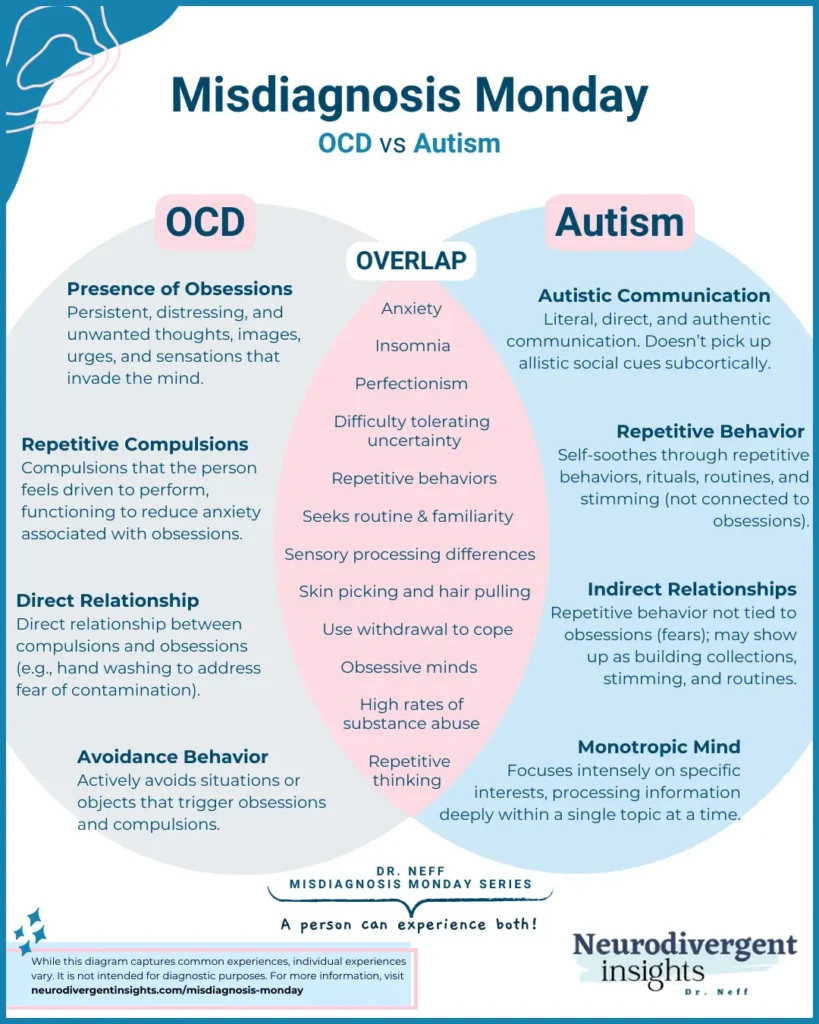

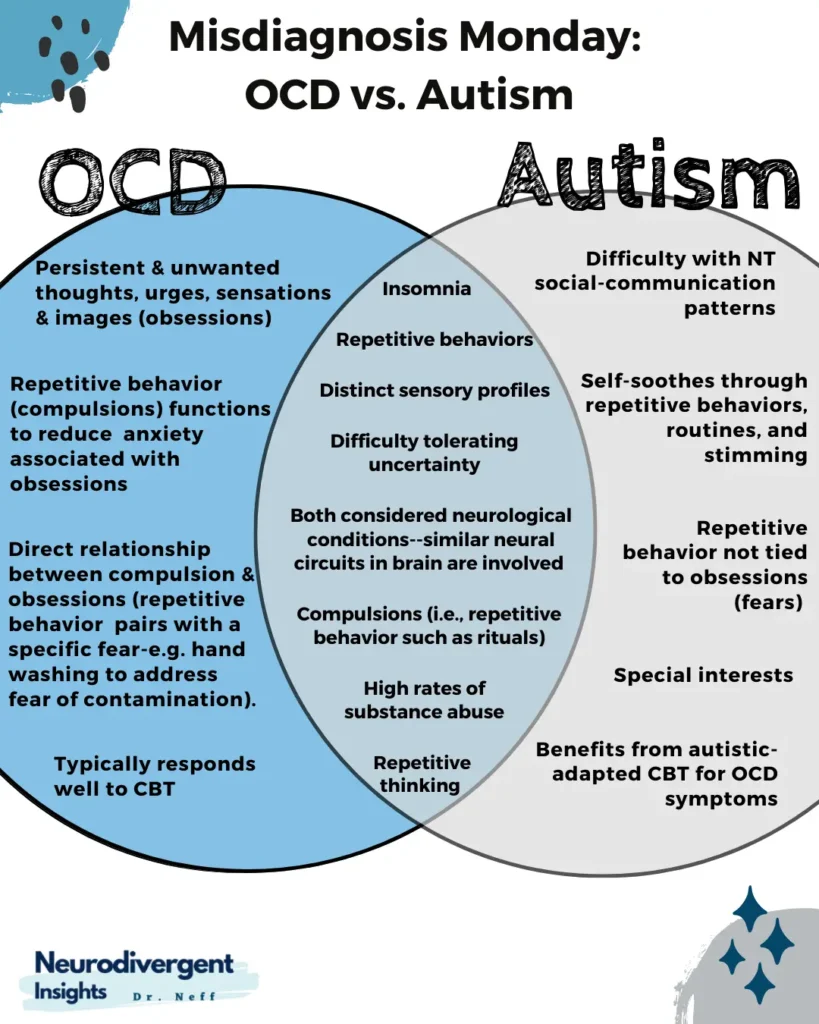

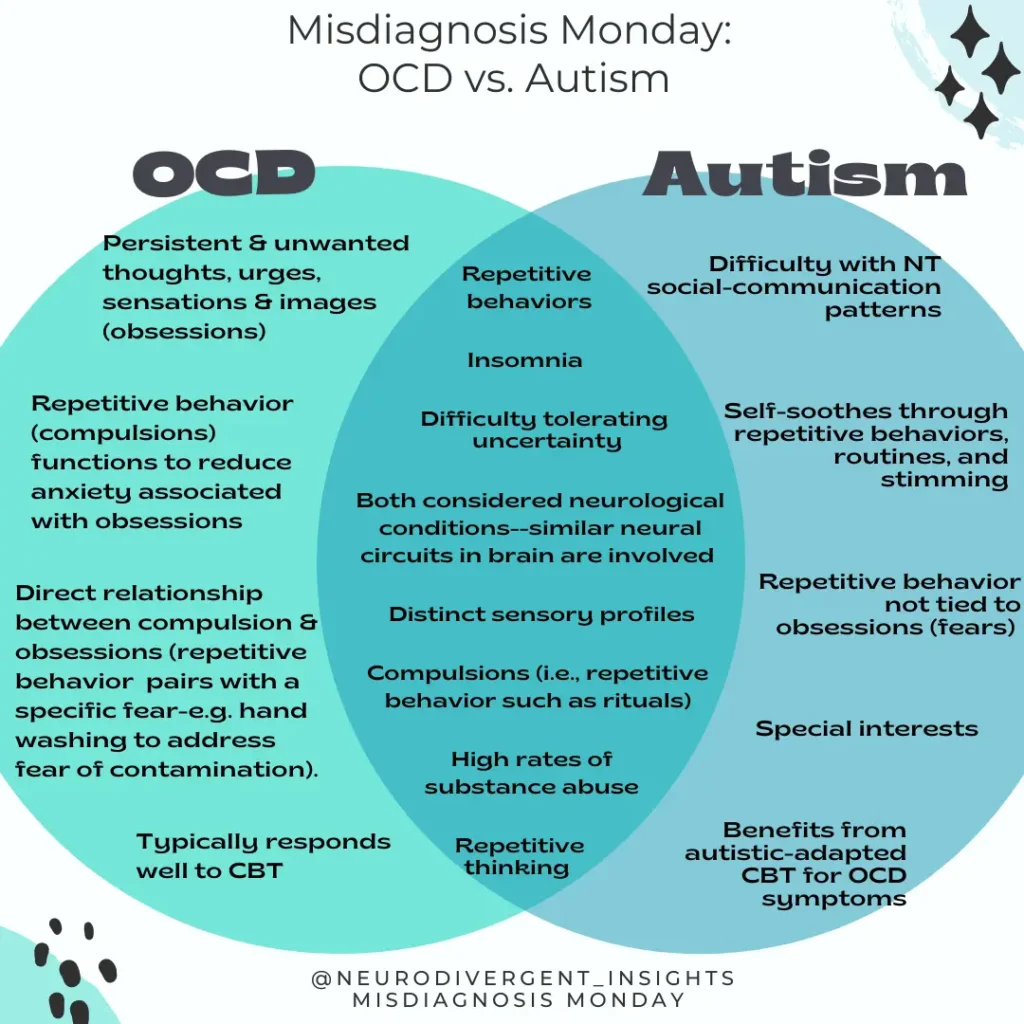

OCD and Autism Overlap

Until recently, OCD was classified as one of the anxiety disorders. Anxiety conditions are one of the most common co-occurring conditions among Autists, with as many as 40% of us meeting the criteria for at least one co-occurring anxiety disorder (specific phobia, generalized anxiety, OCD, etc.) (Van Steensel et al.). Following are some recent research findings regarding co-occurrence:

Van Steensel et al., 2011 meta-analysis found that 17% of Autistic young people also had OCD.

It is speculated that a larger proportion of people with OCD are Autistic. A population-based study in Denmark found familial links between OCD and Autism. They found that people diagnosed with Autism were 2x as likely to be diagnosed with OCD later in life. And people diagnosed with OCD were 4x more likely to be diagnosed with Autism later in life (Meier et al., 2015).

A study in the UK (Wikramanayake et al., 2018) involving 73 adult outpatient patients with OCD measured autistic traits using the Autistic Quotient (AQ) and found that 47% scored above the clinical threshold, 27.8% met full diagnostic criteria for Autism. It is speculated that a larger proportion of people with OCD may also be Autistic.

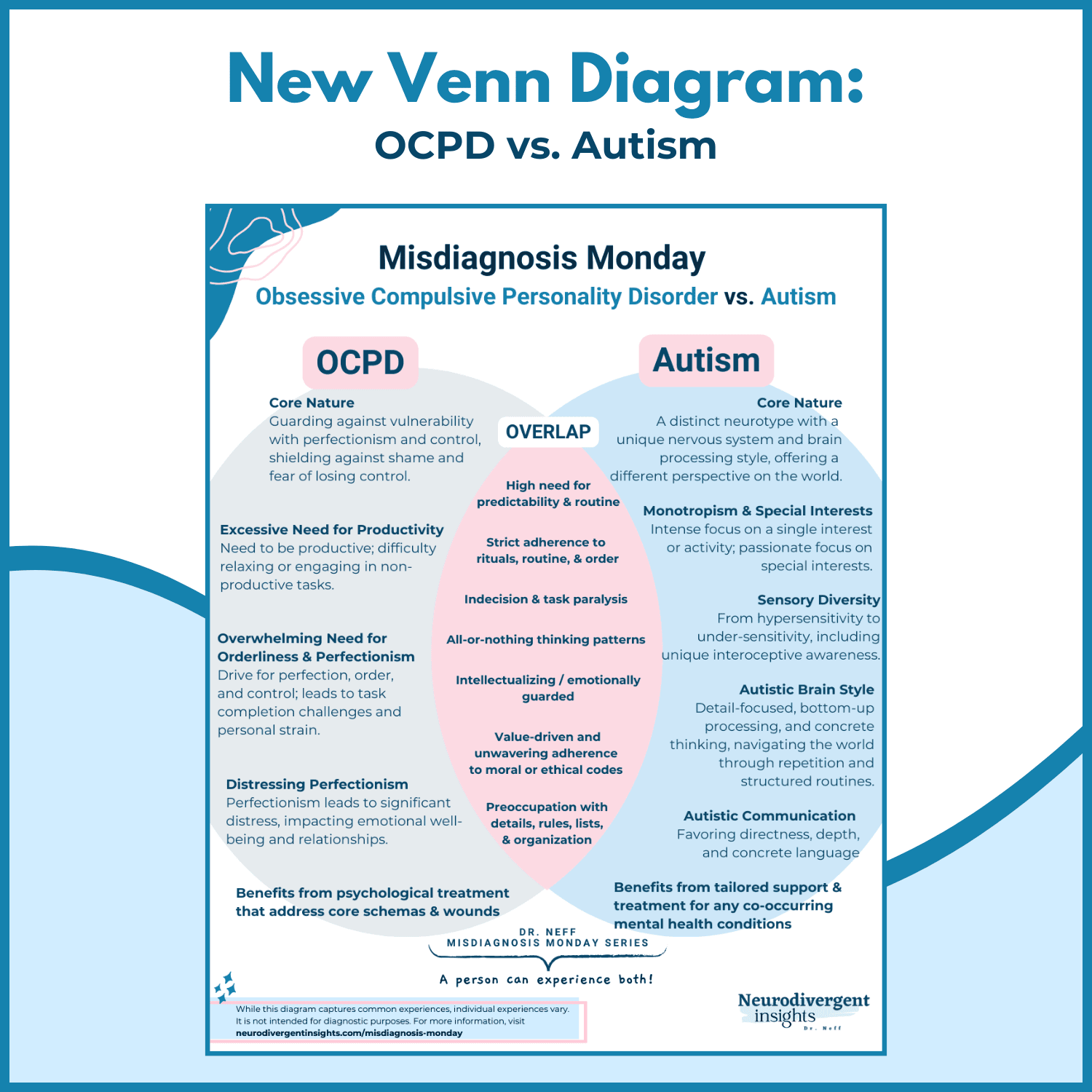

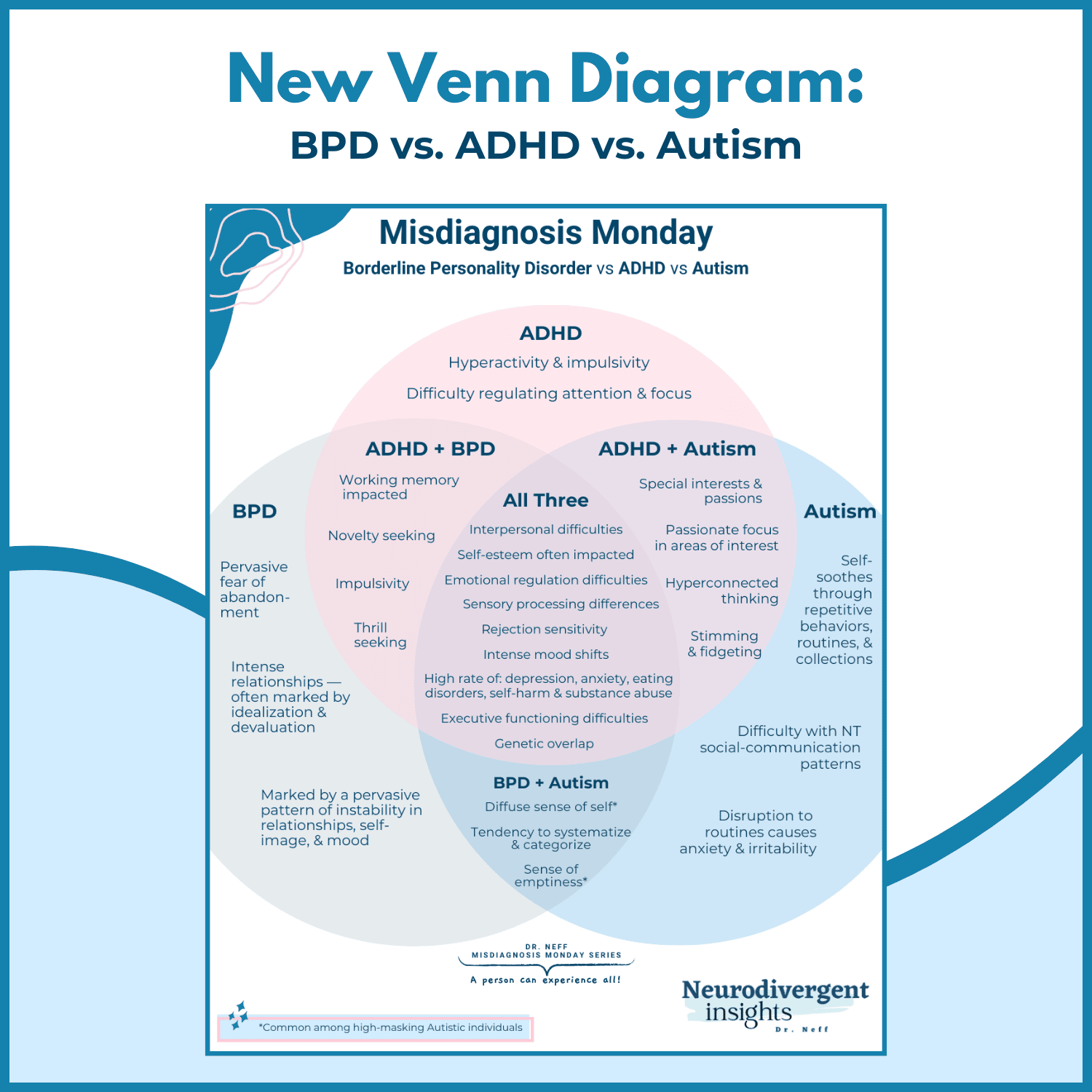

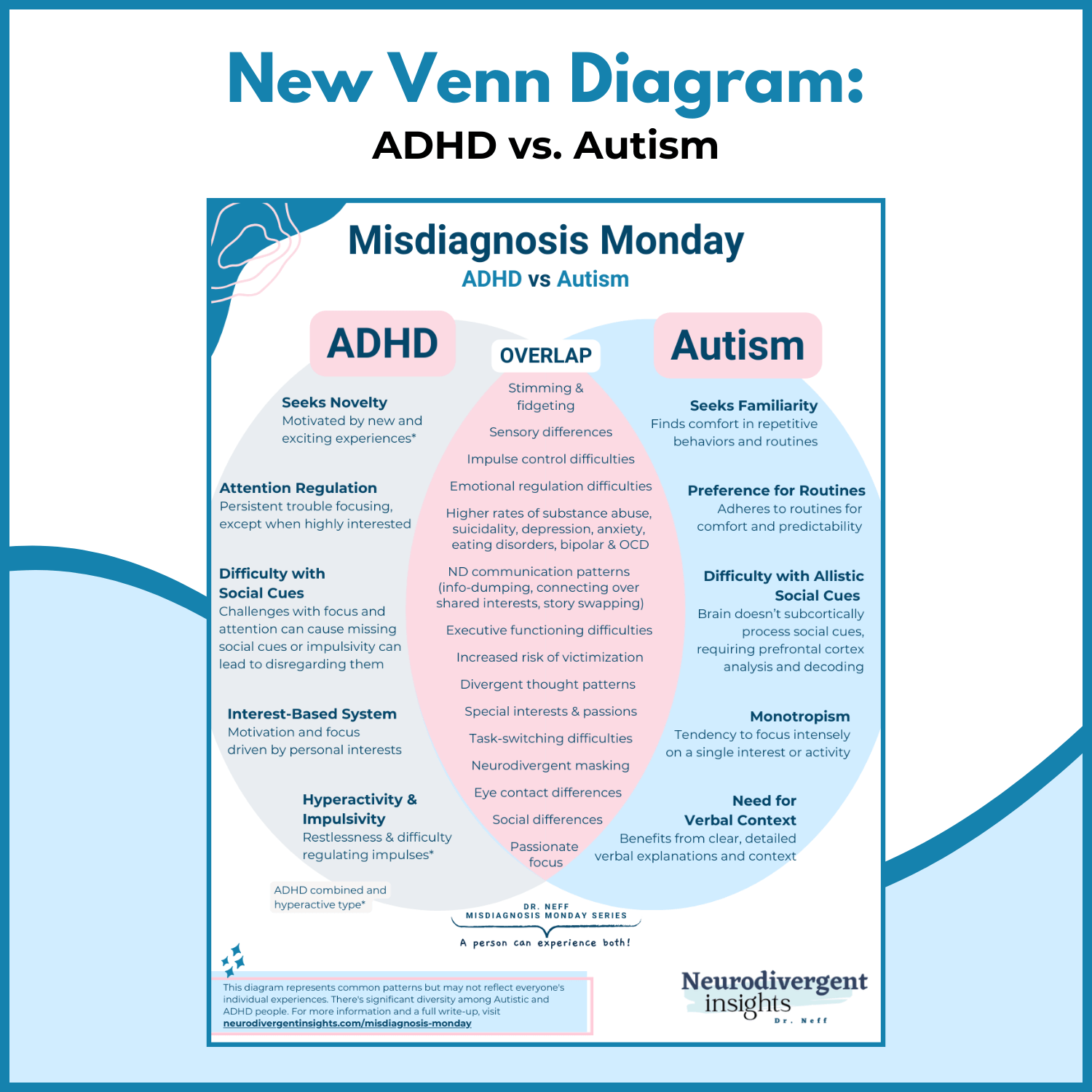

Overlapping Characteristics

While the function of the symptoms and behaviors differ between the two conditions, there are several overlapping characteristics and features of Autism and OCD:

People with both conditions can have unusual experiences to sensory experiences (Ruzzano et al., 2015).

Children with OCD are more intolerant of sensory stimuli, which can lead to ritualistic behavior (Hazen et al., 2008).

Sensory processing sensitivities (particularly oral and tactile hypersensitivity) were linked with OCD symptoms later in life (Dar et al. 2012)

Unusual sensory interests may be key to understanding the link between Autism and OCD and may suggest different pathways to compulsive behaviors (sensory-based vs. cognitive-based pathways, etc.) (Ruzzano et al., 2015).

Autists have more compulsions in general than neurotypicals (Ruta et al. 2010)

OCD rituals may resemble repetitive behaviors; however, the function is different (the function is to reduce the distressing thought/fear/anxiety), while for the Autistic, it is more often tied to our sensory processing and is a method of self-soothing (Ruzzano et al., 2015).

Both are considered neurological conditions and have similar neural circuits involved (the caudate network linked to both OCD and Autism). This area of the brain is connected to compulsive adherence to routines and stereotyped behaviors in Autism and is associated with compulsions in OCD (Qiu et al,, 2017; Zike et al., 2017, Langen et al., 2009).

What Happens When They Co-Occur?

It is essential to know when both conditions are co-occurring as treatment recommendations may differ for Autists with OCD. People with both conditions tend to have unique experiences that are distinct from people who have just one of the conditions on its own. For example, people with both conditions can have unusual sensory experiences (Ruzzano et al., 2015). CBT (unless adapted) may provide limited relief to those who have both (Jassi et al., 2021; Flygare., 2020 Murray 2015).

A study done by King et al., 2009 found that pharmaceutical treatments that were effective in reducing symptoms of OCD were not as effective in individuals with autism (King et al., 2009).

Autists often do better when CBT treatment is adapted, including the incorporation of special interests, more visuals, the inclusion of parents in treatment, adding emotional recognition and recognition into treatment, including length of treatment, and having exposures be client-led (Jassi et al., 2021).

Clinician’s Corner: How to Spot the Difference

Understand the function of repetitive behavior. Evaluate if there is a functional relationship between repetitive behavior and fear. In the context of OCD, there will be a direct relationship between obsessions and compulsions. Compulsions (i.e., repetitive behavior) are a way of coping with and reducing obsessions.

Given the high co-occurrence of OCD and Autism, consider regularly screening for Autism using the AQ or other screeners.

Attend to how the person is receiving information. Are they high-context (bottom-up) thinkers and communicators? Do they do better with visual information and processing? (These forms of processing information are characteristic of Autistic modes of processing information).

Consider the sensory profile (while also being aware that folks with OCD also have some hypersensitivities).

Assess for Criteria A (for a review of DSM criteria for Autism, see the strength-based criteria summarized in this article).

Autism Screeners

AQ: Autism Spectrum Quotient

Alexithymie Questionnaire(not technically an autism screener but Alexithymia is common among Autistics).

The Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised (RAADS-R) is a self-report questionnaire designed to identify adult autistics who “escape diagnosis” due to a subclinical level presentation.

The Adult Repetitive Behaviors Questionnaire-2 (RBQ-2A) is a self-administered questionnaire that measures restricted and repetitive behaviors in adults.

The Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) is a self-report measure of social camouflaging behaviors in adults. It may be used to identify autistic individuals who do not currently meet diagnostic criteria due to their ability to mask their autistic proclivities.

OCD Screener

References

Dar, R., Kahn, D. T., & Carmeli, R. (2012). The relationship between sensory processing, childhood rituals and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43(1), 679-684.

Hazen, E., Reichert, E., Piacentini, J., Miguel, E. C., do Rosario, M. C., Pauls, D., & Geller, D. (2008). Case series: Sensory intolerance as a primary symptom of pediatric OCD. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 2004(20), 4.

Jassi, A., Fernández de la Cruz, L., Russell, A. et al. An Evaluation of a New Autism-Adapted Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Manual for Adolescents with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 52, 916–927 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-01066-6

King B. H., Hollander, E., Sikich, L., McCracken, J. T., Scahill, L., Bregman, J. D., … Ritz, L. (2009). Lack of efficacy of citalpram in children with autism spectrum disorders and high levels of repetitive behaviors. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 583-590.

Meier, S. M., Petersen, L., Schendel, D. E., Mattheisen, M., Mortensen, P. B., & Mors, O. (2015). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorders: Longitudinal and Offspring Risk. PloS one, 10(11), e0141703. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141703

Flygare, O., Andersson, E., Ringberg, H., Hellstadius, A. C., Edbacken, J., Enander, J., Dahl, M., Aspvall, K., Windh, I., Russell, A., Mataix-Cols, D., & Rück, C. (2020). Adapted cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder with co-occurring autism spectrum disorder: A clinical effectiveness study. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 24(1), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319856974

Murray K, Jassi A, Mataix-Cols D, Barrow F, Krebs G (2015) Outcomes of cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive–compulsive disorder in young people with and without autism spectrum disorders: a case controlled study. Psychiatry Res 228(1):8–13

Ruzzano, L., Borsboom, D., & Geurts, H. M. (2015). Repetitive behaviors in autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder: new perspectives from a network analysis. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 45(1), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2204-9

van Steensel, F. J., Bögels, S. M., & Perrin, S. (2011). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Clinical child and family psychology review, 14(3), 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0097-0

Qiu, T., Chang, C., Li, Y., Qian, L., Xiao, C. Y., Xiao, T., … & Ke, X. (2016). Two years changes in the development of caudate nucleus are involved in restricted repetitive behaviors in 2–5-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 19, 137-143.

Ruta, L., Mugno, D., D’Arrigo, V. G., Vitiello, B., & Mazzone, L. (2010). Obsessive–compulsive traits in children and adolescents with asperger syndrome. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19(1), 17-24.

Yuhas, Daisy. (2019). Untangling the ties between autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Spectrum Deep Dive: URL: https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/untangling-ties-autism-obsessive-compulsive-disorder/

Zike, I., Xu, T., Hong, N., & Veenstra-VanderWeele, J. (2017). Rodent models of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Evaluating validity to interpret emerging neurobiology. Neuroscience, 345, 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.09.012