How Are ADHD and Bipolar Related?

In my training, we learned the DSM categorically. Meaning we went through the DSM chapter by chapter and learned the different conditions one by one. But life is rarely as neat and tidy as it shows up in textbooks. When a person has one condition, the odds of them having a co-occurring condition increases substantially. Especially in the context of neurodivergence (Autism, ADHD, OCD, Bipolar, and more), these conditions frequently have other conditions come along for the ride.

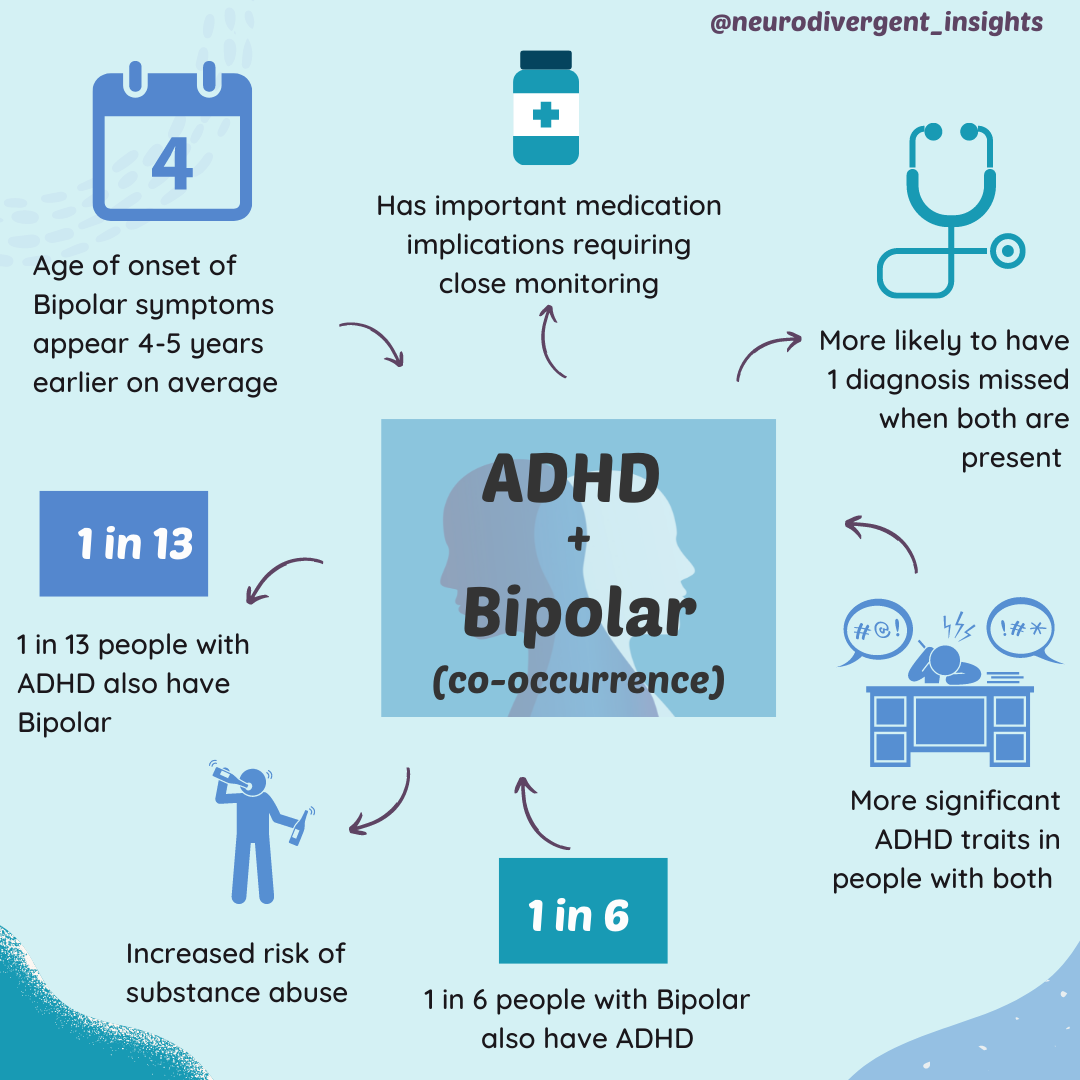

For example, 2/3 of people with ADHD have a co-occurring condition. When a person has ADHD and another condition this is referred to as “complex ADHD”. Complex ADHD can manifest in a different presentation, and needs specific support. For example, it may require that treatment and medications be adjusted and closely monitored. ADHD and Bipolar is one such example of co-occurrence conditions that can result in a different clinical presentation and requires adjusted medication and psychotherapeutic treatment approach. Below is a summary of several research studies that have looked at the co-occurrence of ADHD and Bipolar.

Co-Occurring ADHD and Bipolar:

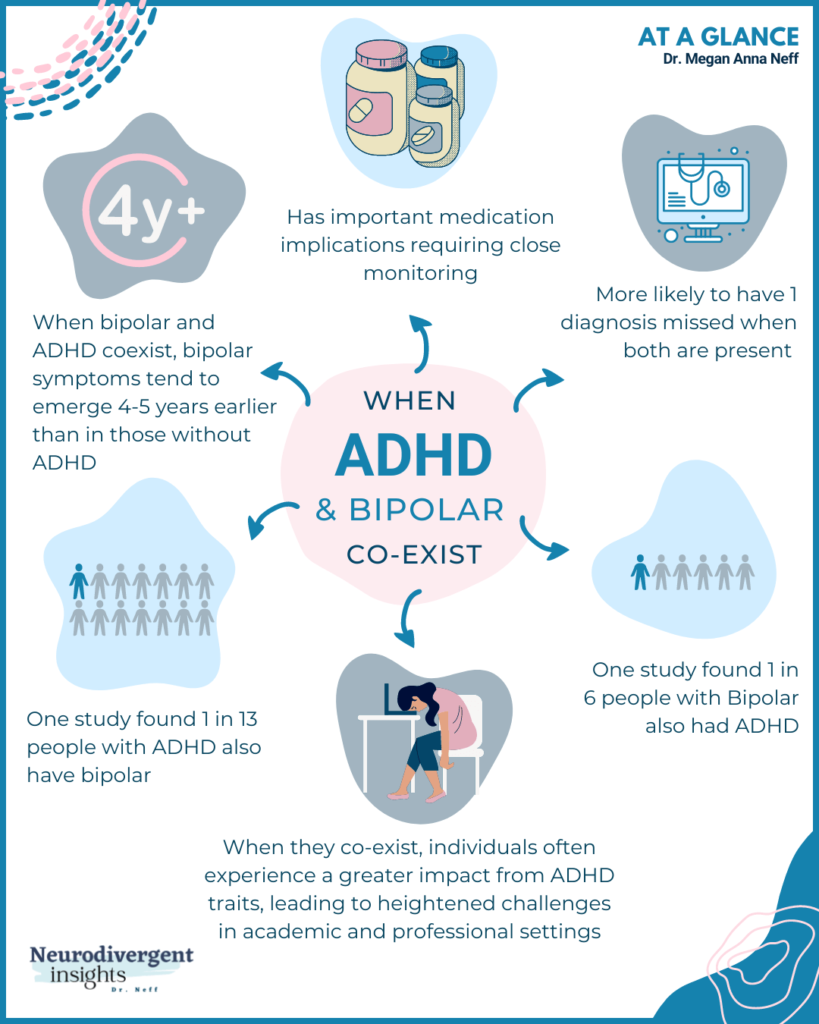

An estimated 1 in 13 people with ADHD have co-occurring bipolar (Schiweck et al., 2021)

An estimated 1 in 6 people with bipolar have ADHD (Schiweck et al., 2021)

ADHD patients are at elevated risk for bipolar, and first-degree relatives of bipolar patients are at elevated risk for ADHD (Schiweck et al., 2021; Tatsiopoulou 2020)

People with both have more severe ADHD symptoms and an earlier onset of bipolar symptoms (Schiweck et al., 2021)

People with both have more frequent episodes of mania and depression and higher instances of additional comorbid psychiatric conditions, including anxiety and substance use disorders (Schiweck et al., 2021)

The risk of substance abuse, victimization, and suicidality increase when both conditions occur together.

The risk that one diagnosis will be missed increases when a person has co-occurring conditions. For example, in the case of ADHD/bipolar, there is a risk one condition is treated while the other is missed, which can have determinantal consequences (Schiweck et al., 2021)

Onset of bipolar symptoms nearly five years earlier in patients with co-occurring ADHD

Early diagnosis and treatment of ADHD can help reduce risks associated with both conditions. There is some evidence that early treatment of ADHD can be protective from the development of future depression, bipolar, and substance abuse. Individuals with ADHD who received stimulant treatment in childhood had lower rates of depression and bipolar disorder later in life compared with individuals who were not treated (Katzman et al., 2017)

Implications for medications (see the last section of this article to learn more).

To learn more about ADHD and Bipolar overlap/co-occurrence/differences, see my Misdiagnosis Monday post on it. For clinicians, this post also includes links to screeners and thoughts on how to differentiate ADHD from bipolar.

Resources:

***Bipolar Resource for Clients: https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/Resources/Looking-After-Yourself/Bipolar (Free, self-paced workbooks for bipolar-a wonderful resource on how to keep a balance, provides a place to record symptoms, and provides behavioral and cognitive strategies to help with managing moods).

References

Katzman, M.A., Bilkey, T.S., Chokka, P.R. et. al. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry 17, 302 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1463-3

Schiweck, C., Arteaga-Henriquez, G., Aichholzer, M., Thanarajah, S. E., Vargas-Cáceres, S., Matura, S., … & Reif, A. (2021). Comorbidity of ADHD and adult bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.017

Tatsiopoulou, P., Porfyri, G. N., Bonti, E., & Diakogiannis, I. (2020). Childhood ADHD and Early-Onset Bipolar Disorder Comorbidity: A Case Report. Brain sciences, 10(11), 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10110883