Reflecting on the diverse needs of humanity has been on my mind this past several weeks, especially with July marking Disability Pride Month. This is a time to celebrate and honor the disability community, recognizing our experiences and the significant progress made over the years. In the United States, Disability Pride Month aligns with the anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a landmark in protecting the rights of disabled individuals.

Disability Pride is about acknowledging the rich history, achievements, and unique experiences of disabled people. It’s a push to increase visibility, foster inclusion, and shift societal perceptions of disability. Admittedly, embracing a disabled identity as something to celebrate can feel counterintuitive, given that disability is often framed as a tragedy.

Many of us also navigate complex emotions and grief related to our disabilities. Therefore, Disability Pride is not just a celebration but an act of resilience and defiance. It involves acknowledging our struggles and intricate feelings while choosing to honor our identity, embrace our strength, and celebrate the ways we contribute to society and culture.

In today’s article, we’ll first lay out the context with some brief history of the disability movement and pride, and then explore the complexity and nuance around disability identity, pride, and the difference between identity pride and a victim mindset.

A Brief History

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

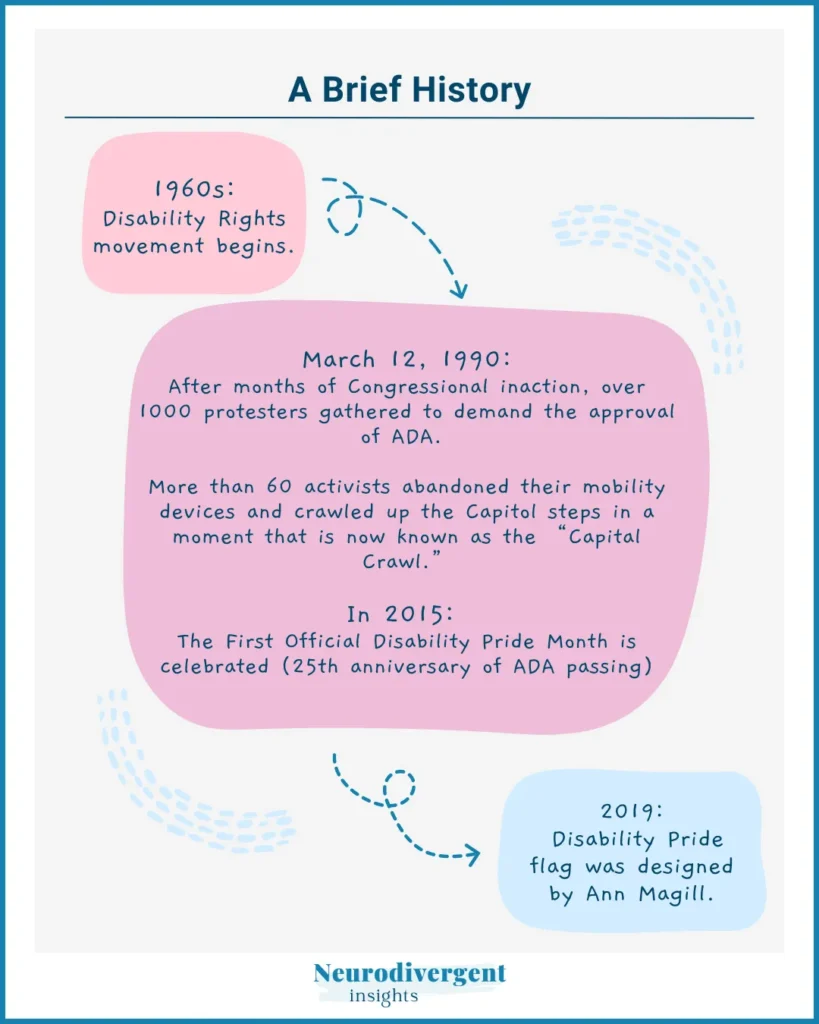

The disability rights movement began in the 1960s. Progress was slow until the landmark “Capitol Crawl” on March 12, 1990. After months of Congressional inaction, over 1000 protesters gathered in Washington, D.C., to demand the approval of the ADA. The chant “What do we want? ADA! When do we want it? NOW!” resonated as more than 60 activists abandoned their mobility devices and crawled up the Capitol steps, casting a spotlight on the barriers faced by disabled people.

Inspired by the Disability Rights movement, Disability Pride is rooted in intersectionality and social justice. This movement aims to transform the negative perceptions and biases commonly linked with disabilities. Serving as a counter to ableism and social stigma, Disability Pride shares theoretical foundations with Queer Pride and Black Pride. It celebrates the contributions of disabled people to society and the historical achievements of the Disability Rights movement. This marks a stark departure from the traditional view of disabilities as shameful and tragic (Source: Wikipedia).

While the first Disability Pride Day was held on October 6, 1990, and was also held the following year, the events fizzled out after the death of lead organizer Diana Viets. The first Disability Pride Month was celebrated in July 2015, which marked the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Disability Pride Flag

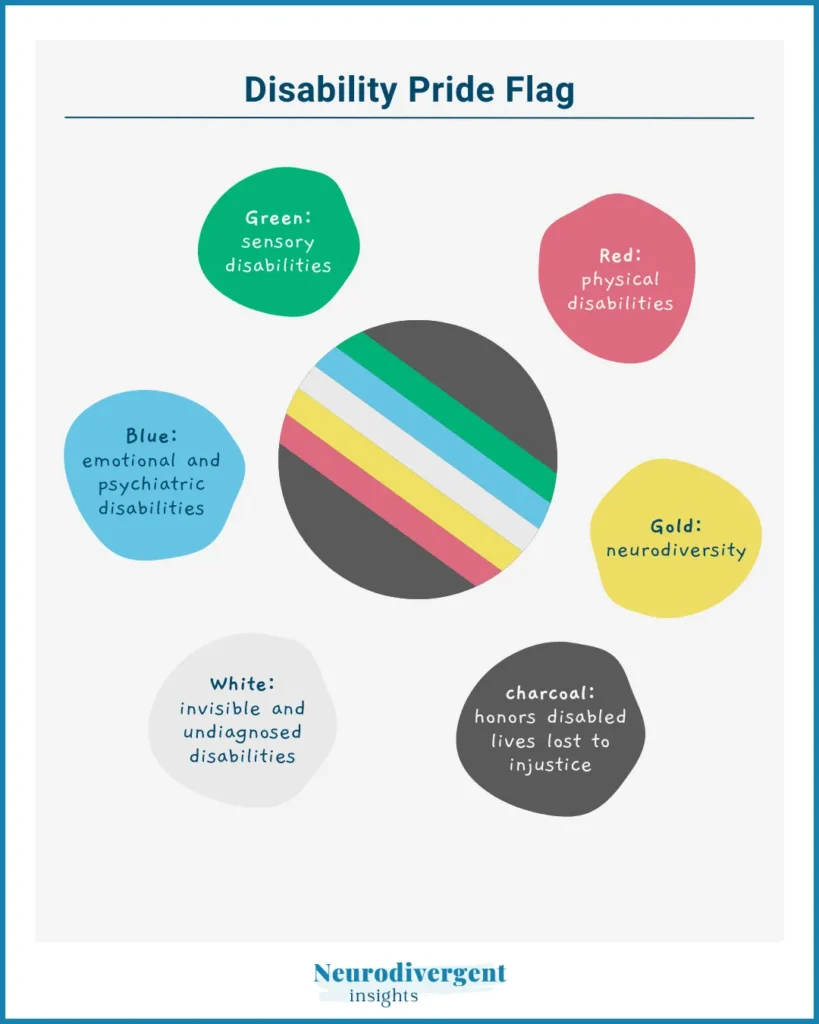

The Disability Pride flag is newer to the scene. It was originally designed in 2019 by writer Ann Magill, who has cerebral palsy. It symbolizes solidarity, pride, and acceptance. Motivated by her disappointment at the limited visibility of an ADA anniversary event, Magill created the flag to raise awareness. The original design featured brightly colored zigzagging stripes on a black background, representing the barriers people with disabilities navigate.

However, feedback from the community, particularly concerning visually triggered disabilities, led to a redesign in 2021. The updated flag features straightened, muted stripes and reordered colors for better accessibility, symbolizing various types of disabilities:

red for physical disabilities

gold for neurodiversity

white for invisible and undiagnosed disabilities

blue for emotional and psychiatric disabilities

green for sensory disabilities.

And finally, the charcoal gray background mourns disabled people who have died due to ableism, violence, negligence, suicide, rebellion, illness and eugenics.

You can read more about the flag and it’s history here.

Why Disability Pride Matters

Community and Belonging: People with disabilities often face stigma and isolation, making the sense of community and belonging vital in combating these challenges.

Advocacy and Awareness: Disability Pride events highlight the importance of advocacy and the ongoing efforts needed to improve accessibility and inclusion. They bring attention to the issues faced by the disability community and promote change.

Positive Identity: The stigma surrounding disability can make it difficult to embrace a positive identity. However, adopting a positive identity is one of the most protective steps one can take when belonging to a stigmatized and marginalized group. Disability Pride encourages this positive self-perception (more on identity in a moment).

Understanding Disability

There are various models to understand disability, including:

The Medical Model: Views disability as a problem to be fixed or cured.

The Social Model: Sees disability as occurring at the intersection of a person’s impairment and societal barriers and attitudes. This model emphasizes removing these barriers to create an inclusive society.

Recognizing the different frameworks for understanding disability can be deeply empowering. Each model has its strengths and limits, and it’s not about finding the “right” one but understanding there are several different frameworks for talking and thinking critically about disability (to learn more about different models of disability check out Kaligirwa’s (BlackSpectrumScholar) resources on Instagram. She has a two part series that explains different models of disability (part one here and part two here).

Diversity of Disabled Experiences

There is great diversity in how people experience disability. Disability isn’t a one-size-fits-all concept; it varies greatly from person to person and can be influenced by numerous factors. Here are some key aspects to consider:

Dynamic vs. Static: Identity can be fluid, ebbing and flowing with time and circumstances, or it can be more constant and unchanging. For instance, I have several dynamic disabilities. There are days when my chronic fatigue and brain fog significantly impair me, making daily tasks feel overwhelming. However, there are also days when these issues are less pronounced, and I feel more capable and less impacted by my disabilities. There are also certain environments where I feel more impacted by my autism and environments where I am not impacted. This dynamic nature means that my experience with disability is not constant; it changes over time, reflecting the complex and variable nature of living with a disability. Conversely, some people’s experiences with their disabilities are more static and their challenges remain relatively consistent over time.

Visibility: Disability can be either visible or invisible. Some disabilities are apparent, such as being a wheelchair user which can lead to immediate recognition and sometimes unwarranted assumptions and comments from others. Having a visible disability can lead to more overt stigma and prejudice from others. In contrast, invisible disabilities, such as chronic pain, mental health conditions, or sensory sensitivities, are not immediately noticeable. This can result in misunderstandings and the need for individuals to constantly explain or justify their experiences. The visibility of a disability can influence how one navigates the world and interacts with others.

Innate vs. Acquired: Disabilities can be innate, present from birth or developed early in life, or acquired later due to illness, injury, or other life events. Innate disabilities might shape a person’s identity from a young age, integrating into their sense of self as they grow. Acquired disabilities, on the other hand, can bring about significant life changes and require an adjustment period as individuals adapt to new limitations and reframe their identity. Both innate and acquired disabilities can come with complex emotions.

Some Facts About Disability

1 in 4 people in the United States have a disability (Source: CDC)

Disability is a unique identity group, in that it is one of the few marginalized identity experiences that is an equal opportunity group. While many are born disabled, it is also a group that any human can join at any point in their life, and most do if they live long enough.

Disability Pride and The Complexity of Identity

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Now that we have a framework for disability, let’s delve into the complexity surrounding disabled identity, pride, and labels.

Disability Pride Month and identifying as disabled can be a multifaceted experience, especially since many of us navigate multiple disabilities. Personally, I have very different relationships with my various disabilities.

It’s easier for me to embrace and take pride in my autism and ADHD, whereas I have a more strained relationship with aspects of disability related to long COVID, chronic pain, and chronic fatigue syndrome. This complexity reminds us that pride can coexist with challenges and ongoing struggles. It also invites us to embrace multiplicity, recognizing that we may have different experiences with different parts of ourselves and our disabilities.

If I have a disability am I disabled?

Disability encompasses a broad range of experiences, from physical and intellectual disabilities to ADHD, autism, and various mental health conditions, all of which have medical and legal protections. However, identifying as “disabled” is more than a legal status; it’s a personal and social identity that carries its own set of experiences.

You may have a disability and seek accommodations and legal protections for that disability yet choose not to identify as disabled. Taking on “disabled” is a choice of identity.

You’ll notice I’m using “disabled” rather than “person with disabilities.” When you embrace “disabled” (similar to using the terms “Autistic” or “ADHDer”), you’re using identity-first language—meaning you are acknowledging this as a core part of your identity which you are not ashamed of. Identity-first language typically reflects pride in owning the identity, whereas person-first language (“a person with autism” or “a person with disabilities”) often functions to distance from the condition. (P.S. if language is new to you, here is a great 60 second read on disability language).

Choosing to identify as disabled is a very personal decision. For some, adopting the identity of disabled is a clear and empowering choice. For others, the relationship to this identity might be more ambiguous, fraught with questions of belonging and imposter syndrome. Moreover, disability can ebb and flow, influencing how we see ourselves and how we choose to identify at different times.

In a recent episode of the Ologies podcast, Guinevere Chambers aptly puts it: “It often feels like this is a secret club … you have to be disabled enough to get in.” Chambers reflects that it is a “self-chosen identity. If you feel like your ADHD or whatever it is you’re dealing with affects your day-to-day life, your relationships, or your experiences of the world, your body, and your mind, you can choose to identify as disabled. You have the right to say that you are disabled, but you also don’t have to. Many people with mental health conditions or in the Deaf community may choose not to identify as disabled, and that is entirely up to the person.”

So, is autism or ADHD a disability? 100% yes. To say otherwise jeopardizes the protections of those in our community who need them the most. Are you disabled? This is a more nuanced and personal discovery for you to consider.

Identity Pride Vs. Victim Mindset

The first part of this article initially appeared as a newsletter. In response to that newsletter, I received a handful of email replies. I typically enjoy these interactions as they help me learn about my readers and gauge how my thoughts are being received. However, one email, in particular, I would have been fine not to receive. It was from someone telling me to stop with these monthly pride emails, suggesting that some of us don’t like to center our victimness.

The sting of their criticism lingered. My OCD brain, ever the relentless carousel, replayed the critique on an intrusive loop. This (among a hundred other reasons) is why I often silence social media comments, allowing only community members and my email list to access my mind.

While the person who emailed obviously missed the point of disability pride and my intended message, it got me thinking. That email was followed by a week-long conversation in the Learning Nook about disability identity. So, I’ve been marinating on this question:

“What’s the difference between a victim mindset and identity pride?”

I think there is a world of difference, and it’s important to unpack these differences.

Victim Mindset

First of all, I honestly don’t love the term “victim mindset” because it is often used to dismiss the legitimate experiences of those who have been victimized or systemically oppressed. Critiquing a victim mindset is not about invalidating the real and profound experiences of marginalized groups, whose victimhood has often been systemically delegitimized, especially in contexts like Black victimhood in America.

When I discuss a victim mindset, I’m referring to a psychological pattern. It’s a deep-seated cognitive bias where an individual becomes stuck in the identity of being a victim. Research by Rahav Gabay and colleagues defines interpersonal victimhood as “an ongoing feeling that the self is a victim, generalized across many kinds of relationships.”

This pattern of thinking places oneself as the perpetual victim and others as the perpetrators. The victim mindset is characterized by:

External Blame: Overemphasizing the impact of other people’s actions while underemphasizing one’s own role. For instance, someone with a victim mindset might believe, “If so-and-so would just fix their behavior, I’d finally be happy.”

Powerlessness and Helplessness: Feeling powerless and blaming others for personal circumstances, rather than identifying ways to regain control or improve their situation.

Focus on Grievances: Fixating almost entirely on how others make life difficult, rather than on personal actions that could lead to improvement.

Discounting Personal Contribution and an External Locus of Control: A tendency to discount one’s own contribution to outcomes. Individuals with a victim mindset tend to have an “external locus of control,” meaning they feel things happen to them and they have little ability to impact change. In contrast, a strong internal locus of control is when we feel we have the agency to make change happen.

Other features of a victim mindset include a lack of empathy for the pain and suffering of others and a tendency for moral elitism (accusing others of being immoral while seeing oneself as supremely moral).

This mindset can be challenging to address in therapy because individuals often seek validation for their victimhood or want the therapist to fix the other people in their lives. Therapists may inadvertently reinforce the victim mindset or become entangled in a sense of helplessness unless they can recognize and understand these dynamics.

This mindset can also be seen in group dynamics, where in-group members see themselves as victims and out-group members as perpetrators. This is observed across various communities and appears to be increasingly taking root in the neurodivergent community, where narratives often paint a stark division between neurodivergent individuals and neurotypicals, who are cast as the perpetrators of harm.

Hopefully, I’ve helped make one thing clear – a victim mindset is not the same as naming and bringing awareness to oppressive systems. Instead, it’s a way of perceiving of the world. It’s a psychological pattern that erodes agency and personal growth, leading to interpersonal difficulties and a tendency to avoid accountability for one’s actions.

For more insights into the social psychology of the victim mindset, I’d encourage you to read the full article by Dr. Scott Barry Kaufman in Scientific American: “Unraveling the Mindset of Victimhood”.

Identity Pride

In contrast, identity pride is about celebrating culture, identity, community, and resilience. It is a positive affirmation of one’s identity, especially in the face of systemic oppression. At the core of identity pride is agency. At the core of a victim mindset is helplessness. In fact, I think identity pride is one of the antidotes to a victim mentality. Identity pride focuses on:

Celebration of Culture: Embracing and celebrating the unique aspects of one’s identity and heritage.

Community and Solidarity: Fostering a sense of belonging and mutual support within the community.

Resilience and Strength: Highlighting the strength and resilience of the community.

Groups that celebrate identity pride are often those who experience stigma. As Erving Goffman described, stigma occurs when a person’s identity is perceived as “spoiled.” Identity pride is a way of reclaiming that identity—not as spoiled, but as something to be proud of. It’s no wonder that reclaiming these so-called spoiled identities as positive ones is incredibly protective for the mental health of queer, neurodivergent, and BIPOC youth. It allows them to resist internalizing their identity as “spoiled.” Identity pride is about embracing who we are, with all our complexities, and celebrating our unique contributions to the human story.

While a victim mindset traps individuals in a cycle of helplessness and dependency, identity pride empowers, fostering proactive engagement with the world. Victim mindset erodes agency, while embracing a positive identity cultivates agency.

So, in my musings on “all these pride” emails and the concept of a victim mindset, my response would be: let’s embrace more identity pride. Let’s name the oppressive systems at work while focusing on agency and empowerment — elements that will help us be more resilient against falling into a victim mindset.

Resources on Disability For Further Learning

Here are some resources for further learning, support, and education.

Organizations, Projects And Video

Sins Invalid: A disability justice-based performance project that centers the work of disabled artists, particularly those who are queer, trans, Black, Indigenous, and people of color. Through performance, workshops, and advocacy, Sins Invalid explores themes of sexuality, embodiment, and the intersections of disability and identity, promoting a deeper understanding and celebration of disabled people’s experiences and perspectives.

Crip Camp (Netflix): Crip Camp is a documentary that tells the story of a groundbreaking summer camp for disabled teenagers in the early 1970s, which helped ignite the disability rights movement and led to significant advancements in accessibility and equality for disabled individuals.

Stella Young Ted Talk, I am Not Your Inspiration Thank You Very Much.

Accommodation/Education/Advocacy Resources

Job Accommodation Network (JAN): Offers a database of accommodation ideas and other valuable resources for disabled people. Although US-based, others can benefit from the accommodation ideas provided. Visit JAN

Podcast Episodes

Ologies Podcast: This episode on Disability Sociology with Disability Sociologist, Guinevere Chambers, highlights the history of the disability movement, the sociology of disability, and much more.

Thoughty Auti: The Stigma Of Cerebral Palsy with Emma Stone, a cerebral palsy advocate and decorated horse riding athlete.

Books

Year of the Tiger by Alice Wang

The Reason I Jump by Naoki Higashida

Equal Access For Students With Disabilities: The Guide for Health Science and Professional Education (The authors have made a free version available for download to increase accessibility. You can find it here.)

Social Media Accounts Worth Following

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the members of the Learning Nook for generously sharing their experiences and resources. Over the month of July, we had several conversations about disability and identity, and the vulnerability and lived experiences shared by the community have shaped my own evolving understanding. Many members have also generously contributed their favorite disability resources, which are curated above. Your insights and support are invaluable—thank you.