DSM-5 Criteria for Autism Explained (In Picture Form)

DSM-5 In Picture Form: Autism

I am back with week 2 of my DSM-5 in pictures series (if you missed it you can check out last week’s post on social anxiety here).

Disclaimers, FAQs, and Basic Information on the DSM-5

Why am I creating this series: I am creating this series to increase the accessibility and transparency of the DSM-5 and the clinical tools people like me use when we are giving you (or anyone) a diagnosis. I find the mental health world can be overly mysterious, increasing anxiety and stress for many. I believe this process should be as understandable and transparent as possible. I am using visuals to break down the DSM-5 because, like many neurodivergent people, unless a thing is visual, I have a hard time understanding it!

Disclaimers: This is for educational purposes only and isn’t intended as a substitute for medical advice or to be used as a primary diagnostic tool.

A word on language: I use direct language from the DSM. This is for educational purposes. Much of the language used is deficit-based and pathological in nature. It doesn't mean I agree with all the wording (in fact, I do not!). I have made this choice to increase the transparency of what is actually in the DSM.

What do A, B, and C mean? The DSM is broken into different criteria buckets. While a person doesn't need to have all symptoms of each criterion, they typically need to have all criteria met (A, B, C, etc..) to be diagnosed.

What about international people? The DSM-5 is based in the United States (the Psychological Association of America puts it out). However, the criteria are very similar to the ICD, which is used globally and broadly in medical settings.

Okay, now that we’ve gone over the purpose, intent, and limits of this post. Let’s dive in!

The DSM-5 Criteria for Autism

To meet the criteria for Autism, five buckets of diagnostic criteria must be met (A-E). The ones that we spend the most time with are criteria A and B. Criteria A broadly speaks to social, communication, and relationship differences, while criteria B speaks to routine, structure, repetition, special interests, and sensory issues. The other criteria are used to help differentiate autism from other conditions and/or diagnoses.

Autism Criteria A

Autism: Criteria A

There are three subcategories for criteria A of Autism. All three subcategories must be met in order for criteria A to be met. If a person has 2 of the three subcategories, criteria A would not be met for autism.

In recent years much more research has come out that looks at autism in girls, genderqueer and BIPOC populations. Our thinking about criteria A has historically been based on white cis-boys from affluent families. We are learning about how the patterns described in criteria A may present in more subtle forms or be more masked for many groups. Therefore, it is critical that when working with someone who assesses autism, they understand how to look for these criteria from a cultural lens (understanding how these may present differently in different cultural groups).

For a fantastic deep dive into how criteria A (and B) can look different among girls, go check out this podcast featuring Dr. Henderson, where she walks through the entire DSM-5 for autism for girls. Also, note that many of these descriptions will also apply to genderqueer people and many BIPOC men.

Additionally, to read more about autism and high-masking presentations check out Devon Price’s book Unmasking Autism and Laura Hull’s academic article, “The Female Autism Phenotype and Camouflaging: a Narrative Review.”

Autism DSM-5 Criteria A: Subcategory 1

Autism DSM-5 Criteria A: Subcategory 1

"Differences in social-emotional reciprocity" (DSM language is “deficits”).

Social-emotional reciprocity largely refers to the ability to fluidly and flexibly engage in a back-and-forth conversation. There are many reasons this is hard for us. For one, with a casual conversation, it is hard to know what to expect, and there are many context cues to pay attention to.

Another reason this can be hard for many of us is that we tend to have slower processing speed, particularly when our brains are taking in information from many different sources. Hint, this is precisely what we're asking our brains to do during a social conversation. During a conversation, we need to 1) focus on the content being discussed, 2) consider your response to the speaker, 3) attend to body language (ours and theirs), 4) pay attention to a person's energy, 5) focus on not being too distracted by the environment 6) and more.

This subcategory also captures the difficulty many of us experience in initiating new relationships. Many Autistic people describe dating and flirting as being particularly uncomfortable for this reason!

Note, those who are also ADHDers (particularly hyperactive/impulsive or combined type) are likely to initiate more social contact. They may struggle more with picking up social misses and blunders; however, they often have less struggle with initiating.

It’s important to note that many of these observed difficulties around reciprocity are no longer present when an Autistic person is talking about an area of shared special interest and when communicating with other Autistic people. Furthermore, a common way of showing connection and empathy is to connect people's stories with our own personal stories. Within Autistic-Autistic communication, this tends to be more widely understood while it is less understood by allistic people and may be interpreted as the Autistic person being self-centered or lacking reciprocity.

A final note on reciprocity. Difficulty with reciprocity doesn't always mean we're the ones talking or info-dumping! For example, I am much more comfortable in my role as a therapist or mentor. I am more comfortable when creating space for another person and where limited or no reciprocity is expected of me. Throughout my life, people have often commented on my ability to "draw others out." My conversations often focused on others (I have all kinds of tricks to get and keep the other person talking!). Because this quality was appreciated and didn't cause anyone problems, no one was concerned that I "lacked reciprocity" in my conversations.

Finally, a person may also script and mask, and these patterns won't be observed until the person is too distressed or fatigued to maintain the social mask, but they will be apparent during burnout/times of unmasking.

Autism DSM-5 Criteria A: Subcategory 2

Autism DSM-5 Criteria A: Subcategory 2

“Differences in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction” (DSM-5 language is “deficits”)

Differences in nonverbal communication have a broad range of meanings. From our ability to intuitively perceive and interpret other people's tone of voice, facial features, and body language to our ability to moderate our own! It also includes things like

Eye contact (many of us find it distracting, uncomfortable and particularly struggle with it when trying to focus on talking)

A tendency to have difficulty moderating our tone of voice (volume but also affect)

Difficulty coordinating our words with our affect/body posture

Many of these differences are attributed to brain differences. For example, a study by Monk et al. found that non-autistic people had more activation between their amygdala and temporal lobe during a conversation (the temporal lobe intuitively perceives facial expressions, tones, and non-verbals). Autistic people had a stronger connection (during social conversation) between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. We do not perceive our environment in the same intuitive way, and many of us are working our prefrontal cortex in overdrive as we attempt to take in and de-code all of the details around us!

Many high-masking Autistic people will analytically de-code facial expressions and body signals by recruiting the prefrontal cortex, which may hide many of these struggles. Similarly, a person may rehearse facial expressions and tone of voice to be less flat/monotone. Some Autistic people may be overly dramatic in gestures, particularly if they are theater trained or theater is an area of special interest

Autism DSM-5 Criteria A: Subcategory 3

Autism DSM-5 Criteria A: Subcategory 3

"Differences in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships" (DSM-5 language is "deficits")

The last subcategory for criteria A for autism relates to how we develop friendships, create worlds (imaginative play) with others, and context-shift.

Several things that go into this, so let's break it down:

Overall we have more difficulty initiating and creating friendships. Hull's article shows that, on average, girls struggle with this less; however, they struggle with maintaining friendships. Things like difficulty navigating arguments and all-or-nothing thinking can interfere with friendship maintenance.

Other things that can cause difficulty maintaining friendships have to do with executive functioning, lower social motivation, and the sensory demands involved. I can maintain friendships with people who are comfortable seeing and/or talking to me every six months to a year. Friendships requiring more maintenance and demand are incredibly difficult for me to maintain.

It should be noted criteria A3 doesn't consider Autistic-Autistic friendship. A fantastic study by Crompton et al., 2020 looked at rapport building across neurotypes and found that while it was more difficult to create positive rapport (develop friendship) across neurotype (Allistic-Autistic), the Autistic-Autistic pairings had a much easier time of this. So many of these struggles are not present or not as present when a person is in an Autistic community.

Difficulty with imaginative play and group projects is also common. This likely has to do with difficulty with not knowing what to expect, flexibly (and quickly) changing our minds about how we envisioned a project going, and our mind's tendency to get fixated on the "right" way of doing the thing. While I didn't struggle a great deal with imaginative play as a child, I did struggle quite a bit with group projects and found them incredibly taxing to navigate!

Finally, criteria A3 considers context shifting. This is the ability to shift our tone, language, and general way of being from context to context. This may mean shifting from the context of being at the gym to being at a party to being in class to being in the grocery store. Many of us struggle with the idea that there are "certain rules" or "ways to act" in certain situations that then change in other situations. I consider this an extension of our high value of authenticity despite the context. And due to temporal lobe differences, we don't perceive context in the same way as allistic people.

Another form of context shifting is relational (for example, how you talk to your child vs. how you talk to your boss). Many of us value humans equally despite authoritarian hierarchies. This means we may talk with our boss the same way we'd talk with a friend; this can sometimes be interpreted as disrespectful and lead to professional issues for many of us. Personally, I've always struggled to talk to kids "like kids.” I talk to my kids like mini-adults (aka humans). (Side note, it is always amusing to my whole family when an adult tries to talk to them like a little kid. They will look at me with big eyes, like, "why are they talking to me like I'm stupid”).

Autism DSM-5 Criteria B

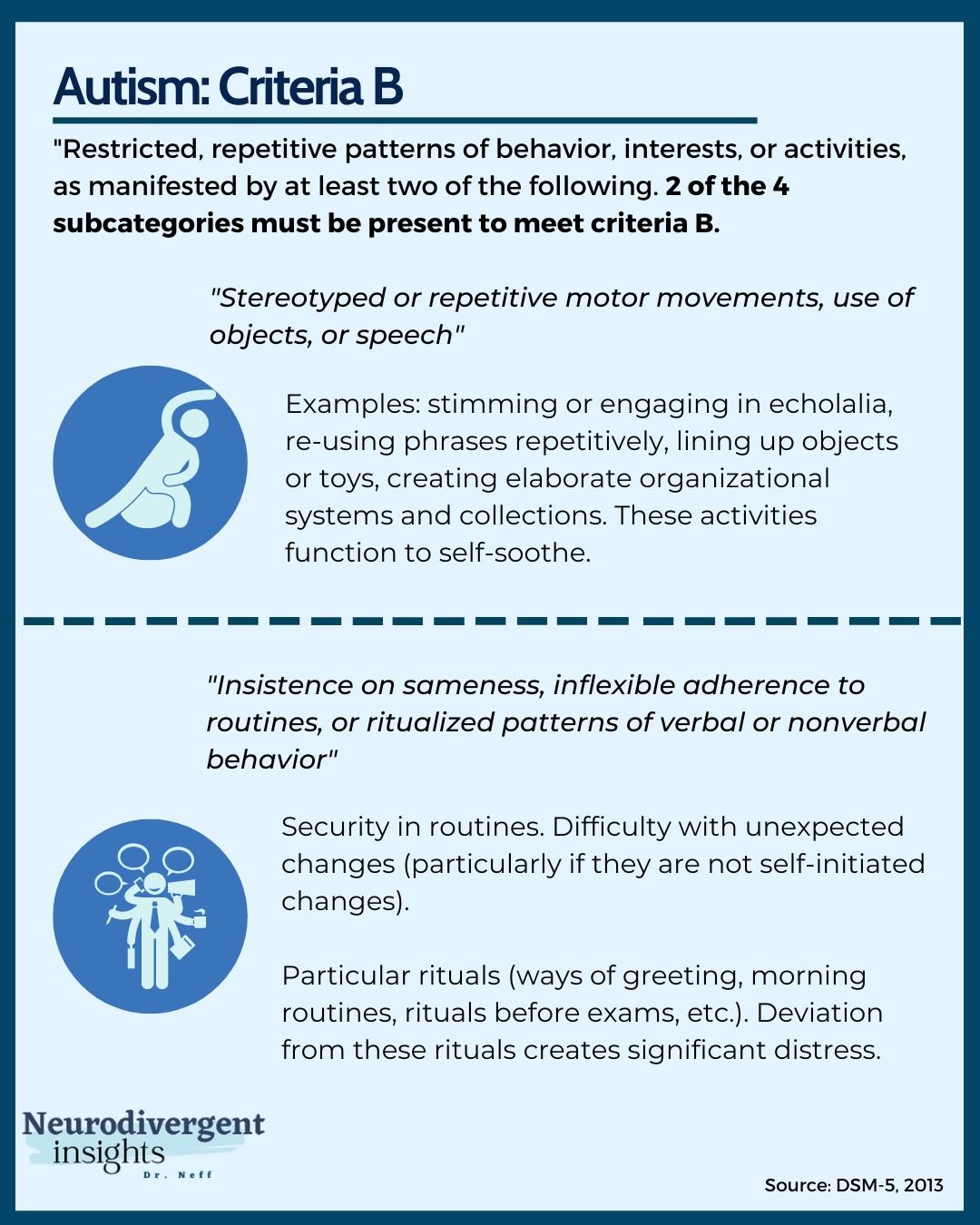

All three subcategories need to be present for the DSM-5 criteria A for autism. For criteria B to be met, only 2 of the four subcategories must be present. Criteria B broadly speaks to our need for routine, structure, knowing what to expect, and our sensory challenges. The direct language from the DSM-5 reads, "Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following."

Criteria B: Subcategory 1

"Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech."

Criteria B1 includes stimming (repetitive movements made typically to self-soothe, such as hand-flapping, pacing, skin-picking, and other body-based movements). The repetitive use of similar phrases and/or words, echolalia (repeating a word or getting a word stuck in your head over and over). It may look like lining up toys and objects and organizing toys based on color in childhood. In adulthood, it may look like having collections and spending large amounts of time organizing and completing these collections. These all serve to self-soothe and function to make the world a more predictable place for us.

Criteria B: Subcategory 2

"Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior."

Knowing what to expect and having a similar routine is incredibly soothing for Autistic people. We experience a great deal of security in our routines and rituals. Many of us experience difficulty with unexpected changes (particularly if they are not self-initiated changes). We may also have particular rituals (ways of greeting, morning routines, rituals before exams, etc.). Deviation from these rituals often creates significant distress.

Note, when ADHD is also present, the person may additionally cause new stimuli, new situations, and change. This can mask some of the Autistic preferences for routine and/or create a ping-pong effect where the person wants both routine and change. This can create competing needs for the Autistic-ADHDers that can be challenging to navigate!

Criteria B: Subcategory 3

"Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus."

Criteria B3 speaks to our tendency to have highly specific and passionate interests. We tend to learn A LOT about our areas of interest and love to talk about them. Sometimes endearingly referred to as "info dumping" (well, I consider it endearing, others consider this term insulting). Our special interests are also how we best connect with people. Many of us can more easily make friends (re criteria A) when the friendship is based around an area of shared special interest.

Special interest is another area that has often been misunderstood for non-stereotypical groups. For example, Hull found that Autistic girls and women tend to have interests that more easily blend in (humanitarian or animal-focused).

Other interests that I often observe include: religious interest (think fundamentalism), identity-based politics and theory (e.g., Queer theory), and social-justice-based interests. In the case where a person has an interest that is more culturally acceptable or "functional," the interest itself may not stand out; however, the intensity around the interest will be notable. The person may constantly listen to podcasts or read books about their interest (or start a website and an Instagram about it:) ) and will likely enjoy talking about their interest. In these cases, it is more important to look at the intensity of the interest rather than the content of the interest.

One final note on special interests. When ADHD is also present, interests may change more rapidly, but the intensity is similar.

Criteria B: Subcategory 4

"Hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment"

The majority of Autistic people are either hypersensitive to sensory input or hypo-sensitive (less reactive) to sensory input. Interestingly, while men tend to have more social-communication difficulties, Autistic women tend to have more sensory sensitivities (there is no detailed research on genderqueer people; however, higher sensory sensitivities have been observed within the Trans population in large).

Examples of sensory sensitivities might include difficulty with light, strong smells (particularly chemical smells like perfumes and artificial toxins often put in cleaning supplies), difficulties with specific food textures, difficulty with tags and clothing textures, and discomfort with touch (particularly light touch). Someone with hypo-sensory responses may have a dulled experience of pain and sensory input.

Criteria B4 also includes "unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment." This may mean having a high interest in visual patterns (and a tendency to become fixated on them), a craving for tactile experiences (for example, touching surfaces, or smelling objects when entering a room).

Autism Criteria C-E

In the DSM, the last few criteria of any diagnosis code typically have to do with the disqualifies or rule-outs. The same is true here.

Criteria C: Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition (i.e., a neurodivergence). As such, it is innate and not acquired, and there must be evidence of it from early in life. It is important to note (and the DSM includes language for this) that Autistic traits may not become apparent until the person is under undue stress or in unsupportive environments. A person may also learn to mask Autistic traits early in life and may escape detection until adulthood.

Criteria D: These experiences must cause suffering. To meet any diagnosis in the DSM, this is essentially a requirement. The experience must either "impair functioning" or cause significant distress. For this reason, there are some psychologists who say that a person may be Autistic but may not meet the criteria for Autism Spectrum Condition. For example, a person may have an Autistic neurotype but experience no difficulty related to it and therefore not identify with criteria D. This gets a bit into the weeds about what is Autistic neurotype vs. what is Autism Spectrum Disorder, and I have mixed feelings about it but find it an interesting concept and understand how some Autistic people may prefer to identify this way.

Also, note that criteria D says "or in other important areas of functioning" mental health and emotional health are also areas of functioning! This language leaves it open for a clinician to consider the impact traits have on a person's emotional and mental well-being. This is critical when assessing high-masking Autists.

Criteria E essentially speaks to the importance of not conflating autism with intellectual disabilities. A person may struggle to pick up social cues and struggle socially due to an intellectual disability, but it isn't autism. Intellectual disabilities and autism co-occur together at high rates, so it can be difficult (and important) to tease out the differences.

Thanks so much for following along and reading; I hope you found this helpful for better understanding the DSM-5 for Autism. If you're interested in more conversations like these, I have lots of articles and e-books that cover autism and commonly co-occurring conditions. I talk about how to spot the difference between autism and social anxiety, autism and BPD, and much more in my Misdiagnosis Monday series.